South Carolina’s Flawed Debut of New Voting System Is a Red Flag for Upcoming Elections

(Photo by Steven Rosenfeld)

When election officials in Richland County, South Carolina, where the state capital of Columbia is located, opened 152 polling places for the Democratic Presidential Preference Primary on February 29, they held their breath.

Richland County, a blue epicenter in a red state, has had a rough time with elections. Like other counties during this past decade, uncounted votes went unnoticed until gaps in oversight were corrected. But on a primary day, elections officials—from those managing countywide logistics to volunteers working polls in schools, libraries, churches, and firehouses—were hoping for a smooth start as a new generation of voting machines was debuting across their county and state.

South Carolina’s all-new voting system was the first that debuted nationally in 2020. It had three stages: a check-in desk as before; a new touch screen computer console where the voter would make their choices and a ballot summary sheet would be printed out; and a new scanner where that ballot card’s votes would be counted. Last summer, the state bought these components from Election Systems and Software (ES&S), the nation’s biggest voting system vendor, for $51 million.

The new voting machines were simple to use and explain to voters. But they also were not trouble-free. By mid-afternoon, many precincts across Richland County saw one-in-five or one-in-six of its new ES&S devices experience a technical failure. Because the primary was a low-turnout contest with slightly above 20 percent of registered voters turning out (the state’s Republicans opted not to have a 2020 presidential primary), the poll managers quickly adapted and kept the voting expeditious and cordial.

Voters did not appear to notice too many interruptions. But officials did as touch screens froze, unprinted ballot cards were spat out, and scanners repeatedly jammed. These issues were atop other concerns noted, such as inadequate privacy screens surrounding touch screens, conflicting instructions from ES&S on which side of the ballot card was to be scanned, and the portable touch screen’s awkward shape for curbside voting in cars to assist voters with disabilities.

The rollout of the new machinery across Richland County was a reminder that getting voting to work well is often dependent on the system’s designers and managers making the right decisions—at the key decision points—in the process. As primary day voting unfurled in one of South Carolina’s largest metro areas, it did not pass that test—promoting questions about what caused it and what could be done before voting next fall.

“It would seem to me that we have seen significant device failure, not so much as to cause problems with running an election, but significant failure for brand-new equipment. The question is what caused it,” said Duncan Buell, one of five Richland County Voter Registration and Elections Commission members and chair of the University of South Carolina’s computer science and engineering department in Columbia.

Buell is among a handful of computer scientists nationally who have studied ES&S for years and has focused on how its systems tally votes. He had just spent five hours visiting 20 precincts, where he talked to clerks, poll workers, and voters and saw the problems—even writing down the serial numbers of sidelined machines to be examined later.

“We know we have a problem,” he said. “We do not know about the cause.”

There were clues. But South Carolina’s statewide debut of a new voting system—the first state among a handful to do so in 2020—is more than a cautionary tale. It was the latest example, following the Democratic Party’s presidential caucuses in Iowa and Nevada, that deploying new voting technology can be unexpectedly marred.

A Hopeful Start

Early voting in South Carolina’s Democratic primary began several weeks before at county offices in downtown Columbia. But the big test came on February 29 with precinct voting. The county had supplemented training materials provided by the state, which bought the voting system, programmed its ballot design and distributed supplies including the ballot paper to be used in the marking devices and scanners.

At local precincts, where most of the clerks and managers (their term for poll workers) were women with years of experience working polls, there was an expectation that voters would have to be walked through the new system. Nell Killoy, the clerk at Meadowfield Elementary School, was prepared. She helped an elderly man who came in after 10 a.m.

“So, slide it in, and it will pull it in for you,” Killoy said, after handing him a long narrow sheet of paper to put into a slot in a ballot-marking console—ES&S’s ExpressVote—that was dominated by a large touch screen. “Once it takes the paper, you will see your ballot,” she continued. “Today, there’s only one election we’re voting in. So these are your choices.”

On the screen were 12 presidential candidates—five of whom had already left the race. It took Killoy less than a minute to explain what to do. But the voter had a question. Should he slide his ballot into the scanner face up or face down? Killoy replied face down, for privacy—even though some ES&S materials had said face up.

Once he left with his ballot and headed for the scanner across the gym, she turned to Buell and quietly raised another privacy issue. The ExpressVote’s computer screen—with the voter’s selections—could be read from several feet away.

“We’re trying to get creative about buying privacy screens,” Buell replied, referring to the folded cardboard enclosures that partly encircle the ballot-marking device (BMD). He was exploring whether local businesses could provide an alternative to ES&S’s options.

Buell had only begun his site visits across Richland County’s southern tier. Before he finished, he would hear other poll managers bring up the privacy issue. He would also receive phone calls from national groups like Common Cause and the League of Women Voters asking whether the new scanners were properly reading the ballot cards—due to ambiguity about which side should face up. (He believed it didn’t matter.)

At other precincts, clerks improvised to address some of these concerns. At one Richland County Library branch, precinct clerk Kimberly Richards, who teaches government at a Christian K-12 school, solved the privacy issue by lining up the BMDs so all the touch screens faced the wall—not the room’s center. She praised the new machinery, compared to an older ES&S system they replaced.

“This is a dream compared to the nightmares of those other machines,” she said, saying the replaced equipment took too long to set up, was heavy to move and had rickety legs that children would pull on. “The only thing with this, we made sure that we turned everything around for privacy.”

While talking to Buell, a trickle of voters walked from one side of the room to the other to carry their ballot card to the scanner. Nobody appeared to be checking if the printout was correct before putting it into the scanner. When asked if voters were verifying their ballots, Richards said, “I haven’t seen that… It’s a robotic thing. Come in. Punch the button. [Then leave, thinking,] ‘Okay, we’re good.'”

At other precincts, voters were pleased to see a mix of paper ballots and touch screens.

“I thought the machines were super,” said a woman trying to sign up people for the local Democratic Party’s meetings. “I loved the machines. I feel like they were as safe as you can get. What do y’all think?”

“I’m a computer scientist who believes that we should get absolutely as much technology out of our elections systems as we possibly can,” replied Buell, who introduced himself. “Because those devices can be hacked. They can be misconfigured. Interesting enough, there was a Twitter post this morning that said that hand sanitizer [in response to the coronavirus] will smudge the [printed ballot] paper and make it unreadable.”

“I wonder if that’s true,” she said.

“It probably is, because it’s thermal paper and printing on thermal,” he replied.

But this voter was pleased with the new system.

“And I just feel that to do a duplicate paper ballot somewhere that presumably will be stored for some period of time is good,” she added.

“If that’s used for any purpose,” Buell replied, drawing a quizzical look. “If there’s some question or if there’s a check. Does the paper actually match up with the results?”

His point was that the underlying ballot records and voting data were only useful if they became part of a routine process of verifying votes and fine-tuning the process.

“It couldn’t hurt,” she replied. “There’s no downside to doing it.”

Equipment Failures

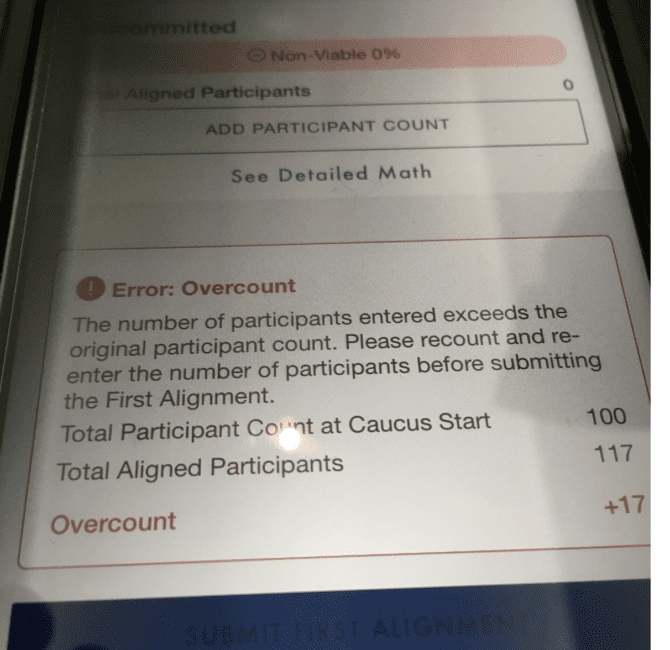

By midday, a more disturbing trend emerged. At many precincts, at least one machine—either the ballot-marking device or the scanner (ES&S’s DS200 model) that counted the ballot summary’s votes, or, both machines, were malfunctioning in different ways.

By the time that Buell finished his rounds of 20 of the county’s 152 precincts, every fifth or sixth new machine had a problem. The ballot-markers prematurely spat out the paper used to print summary cards or their computer screens had frozen up. The scanners had paper jams. A few poll managers told Buell that they had broken the seals to get inside the bin below the scanning apparatus to pull the paper ballot out of its jam.

“This is $51 million of new equipment,” Buell said, after the sixth consecutive precinct with an equipment issue. “We should see minimal failures. We should be seeing one or two across the county, not one every precinct. This really is not a good sign.”

Buell finished his site visits by checking in with Terry Graham, Richland County’s Voter Registration & Elections interim director. Back at the county office, Graham was behind his desk juggling phones. He had a legal pad filled with notes about different precincts.

“Yeah, a similar pattern across the county,” Graham said, putting down the phone and reeling off possible causes—what his staff had narrowed down as likely causes.

The state’s vendor that supplied ballot-printing paper had used a heavier card stock for the first time—maybe causing the jams. Poll workers may not have been properly closing a bar on the scanner. The thumb drives installed in the ExpressVote BMD to program the ballot style had been mass-copied (this was a simple ballot—just one race) and may have been prematurely removed from a programming dock. Some poll managers hadn’t used these machines before, despite several trainings.

After leaving the building, Buell said extreme skepticism was called for. If one new machine was not properly working in each of the county’s precincts, that would be nearly a half-million dollars in gear that was underperforming in its first major test, he said. But, compared to earlier ES&S systems, there were more robust computer records on each machine that could be examined to find out what had happened.

“I don’t think we know until we start looking at the event logs and start comparing notes with other counties,” Buell said. “We have 45 other counties [in the state]. Let’s see what they had. For the places that had these kinds of errors, would there be any commonality?”

On primary day, February 29, Buell said that it was too early to call anyone to get a larger perspective about the statewide debut of ES&S’s new system—not on an Election Day. But he was hoping to get some answers—with an eye to correcting them in a few local elections to be held later this spring. When asked if primary day was an example of growing pains or a learning curve that accompanies any new system, he was clear.

“I’d call it a device failure,” he said. “When it doesn’t work, it’s a failure.”

Also Available on: www.nationalmemo.com