Maryland Spotlights Best Uses of Paper Ballots and Digital Ballot Images to Verify Votes

(Image / Maryland Public Ballot Portal)

In recent weeks, a small drama has escalated in a corner of the election world — one whose stakes underscore that a new generation of voting technology is being introduced across America, and that if state and county officials were willing, the vote counting process could be opened up in markedly more transparent and trustable ways.

At first glance, that tussle appears to be the latest fight between old nemeses. One of the nation’s largest voting system manufacturers, Nebraska-based Elections Systems & Software (ES&S), has threatened to sue a scrappy grassroots group, Arizona-based Audit USA, which posted manuals of its paper ballot scanners online, and since has said that it won’t take them down.

“As a company engaged in what is essentially a public activity, i.e., voting, you must surely recognize that the public has a right to know how election results are produced and that they be publicly verified,” wrote Audit USA attorney Chris Sautter, citing the ‘fair-use’ legal doctrine, where the public interests can supplant copyright protections.

What’s really going on here concerns whether elections will have more or less trustable vote counts. Audit USA is trying to spotlight a positive feature on ES&S’ paper ballot scanners that has become increasingly standard in the latest voting systems: the option to record high-definition digital images of every individual paper ballot scanned. These ballot images can be used to verify vote counts, to resolve recounts, and even to find miscounted votes or malfunctioning scanners before the winners are certified.

What might be lost in this fray is the fact that the digital ballot images — which some states and counties are using, but most are not — not only make vote counting more transparent and trustworthy, but also are so new that many longtime election officials and scholars are not aware of how they can be used to augment verifying the vote. (One example is a 180-page National Academies of Sciences report issued in September that only once mentions ballot images — and blurrily lumps them together under “electronic cast-vote records,” which also refers to more opaque bar-code printouts encoding voters’ choices.)

Nonetheless, the ability to zoom in on the ink marks made by voters, and quickly sort through those images in tandem with examining paper ballots if necessary, is a notable new way of verifying results. But this tool has not received wide recognition, even if it draws on different strengths of using paper and digital records. Instead, industry titans like ES&S are pushing less transparent digital technologies, such as printed bar codes summarizing a voter’s choices, instead of easily understood images of real ballots.

One exception to this overall trend is the state of Maryland, which remarkably has done a complete turnaround when it comes to transparent voting systems. The state was one of the nation’s first to embrace entirely paperless voting after the 2000 presidential election where the messy use of computer punch cards in Florida led the U.S. Supreme Court to stop a presidential recount and declare George W. Bush the winner. But the paperless systems have fallen into disfavor for a variety of reasons — most recently including a susceptibility to hacking—and Maryland, like most of the country, has returned to a system of voting on ink-marked paper ballots that are counted by speedy scanners.

Using paper and digital records

However, Maryland didn’t abandon all electronic tools. Instead, it found that using ballot image counting software, as an independent double check on the scanner-tabulated results, was the best way to verify the count before certifying winners. But like the National Academies report, its use of ballot images as part of a layered approachto auditing election results and conducting recounts has largely gone unnoticed.

Credit: Maryland Public Ballot Portal

“There hasn’t been a whole lot of attention to it,” said Nikki Charlson, deputy administrator of Maryland State Board of Elections, “which is a shame because we think it is extraordinarily valuable.”

“It’s a rich resource. It’s there as a double check,” said Alysoun McLaughlin, deputy election director for Montgomery County, which used the images in two recounts from its 2018 primary. The first was a state legislative race where initially there was an eight-vote winning margin (post-recount, it went to 12 votes). The second was a race for county executive that initially had a 79-vote winning margin (which went to 77 votes).

“The benefit of having paper ballots is spoken about so much in this new era of concerns about cyber security,” McLaughlin said. “But obviously paper has vulnerabilities. There are risks with paper too. So having that electronic copy of the data is also a comfort — to know that you always have these various different tools, different sources to go to. But I think that we have only scratched the surface with what we may ultimately be able to do with this data, with the ability to analyze the images in the way that the Clear Ballot [image auditing] system starts to allow us to do.”

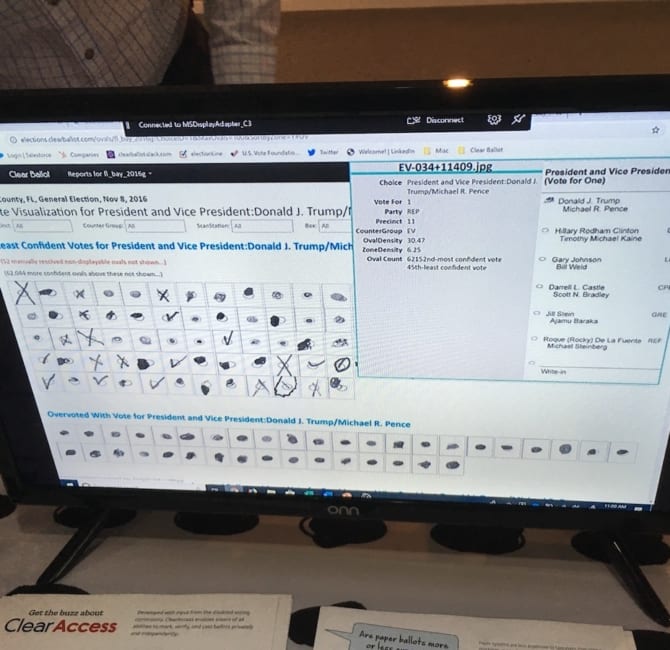

Maryland’s vote-counting protocol is noteworthy in our era where accusations of stolen elections are commonplace. Essentially, the state uses one firm’s technology to read and tabulate the ink-marked ballots — ES&S scanners. But then it uses software from another firm, Clear Ballot, to verify those results and to drill down on discrepancies. Officials do that by importing all the ballot image files into Clear Ballot software, which re-tabulates all of the results, including grading how confidently ink markings appear on ballots.

Credit: Maryland Public Ballot Portal

The first result is a precinct-by-precinct comparison of vote totals from ES&S scanners and Clear Ballot’s tally, which allows election officials to see where precinct totals do or don’t match. The software also assesses and collates the “least confident” ink marks by voters on the ballots — such as Xs or checks, as opposed to neatly filled-in ovals — for closer review. Other marks made elsewhere by voters can be seen, and, if needed, the real paper ballots can be examined on focused, precinct-by-precinct basis.

“When I sit down at my keyboard and start clicking on precincts and looking at the images, and looking to see which ballot images the software has the lowest confidence in, I can see patterns,” McLaughlin said. “I can see, there’s a voter who missed the oval, and they created an oval on their ballot where there wasn’t one. The software is picking up that there is a confidence question on that ballot.”

There are many ways to audit vote counts. There are hand counts of individual ballots, which are slow and can have errors. There are sophisticated statistical analyses, based on drawing a handful of ballots from randomly selected precincts — often called risk-limiting audits — that require some advanced mathematical expertise. And, more recently, there is using ballot images to sift through precincts and ballot categories (early voting, voting by mail, provisional ballots, etc.) more transparently and expeditiously.

Charlson said Maryland tested all three of these approaches in 2016 as it transitioned back from a paper-free to a paper-based voting system, and concluded that Clear Ballot’s image-based system was the best way to verify votes before the results were certified. That’s an important distinction, because this 10-day post-Election Day window is when a contest is still in play, which differs from a post-certification audit that is akin to an academic exercise that won’t change the results.

“We moved from all-electronic voting equipment to paper-based voting equipment,” said Charlson, starting with some background. “We needed to come up with an audit process, because we didn’t have paper ballots before. In the 2016 primary, we did a pilot. We picked two counties, and we did the Clear Ballot audit. We picked a precinct and hand-counted ballots. And then we did a version of the risk-limiting audit. We compared all three audit types, how long it took, and evaluated which one we thought was the best.”

“The recommendation was the Clear Ballot. So in the General Election for 2016, we did the Clear Ballot statewide. And then that turned out to work very well for us. It provided us with a very quick ability to verify the results of the election — all of the results. And it wasn’t too burdensome on local election officials at a time when they don’t have a whole lot of extra time, when they are trying to canvas absentee and provisional ballots.”

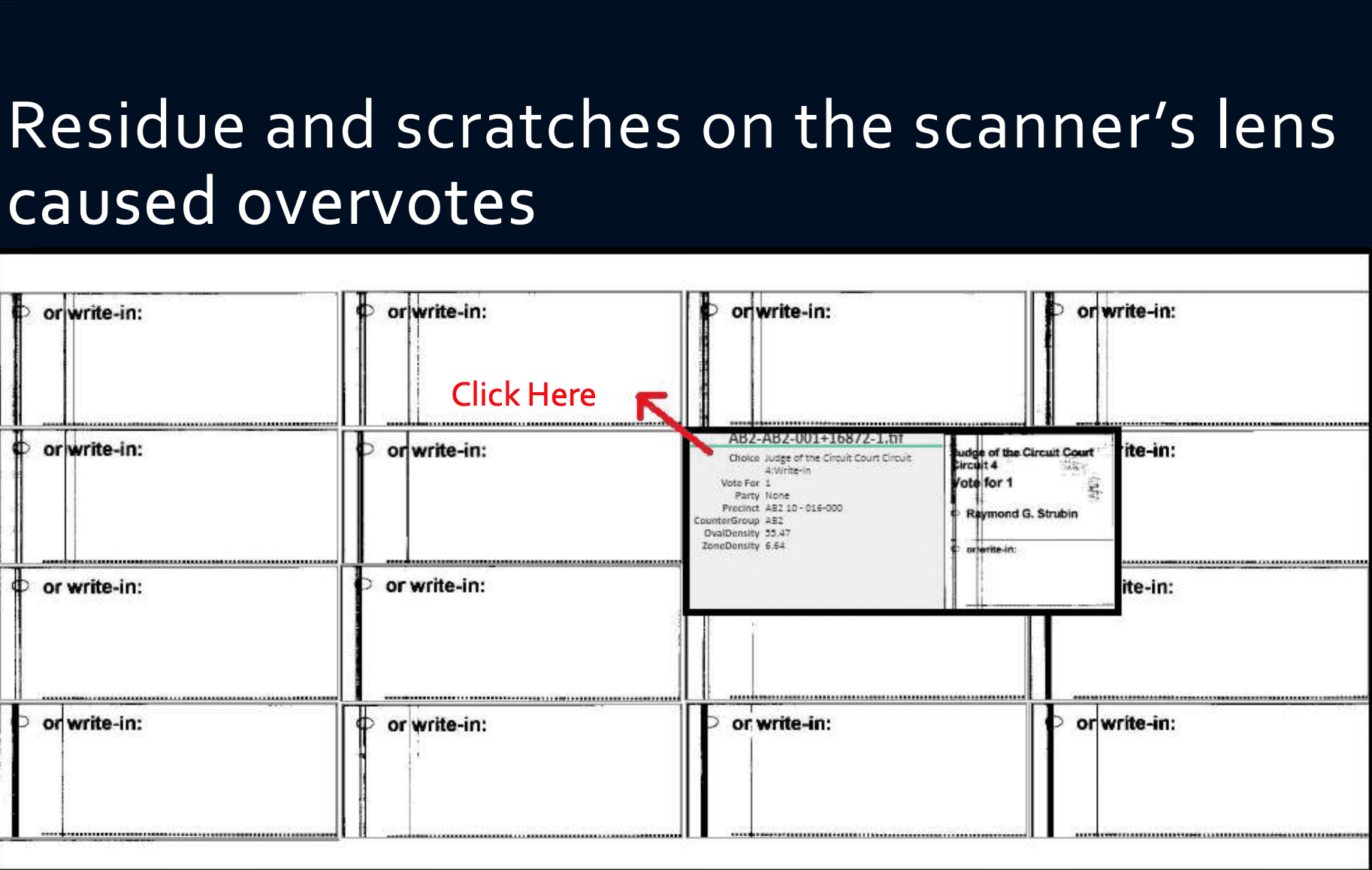

The ballot image software also helped in other ways, according to a slide show that Charlson prepared to present to election officials from other states. The images revealed problems with scanners (pulling two ballots through at once), unread ballots (as seen in scanner images that were too light or too dark), misread ballots (due to folds in paper or printing mistakes from so-called ballot-marking devices — where a touch-screen system prints a ballot as its paper trail) and poll worker error (leaving ballot stubs attached).

“You can see in some of the images where a [paper] fold through the [candidate] write-in box actually was counted as a vote by the voting system. So it either triggered an over vote [that wasn’t counted] or it triggered a write-in where there wasn’t one,” Charlson said. “We found machines that had scratches on the lens. We were able to identify those for needing repair. So it has all these benefits that, as election officials, it’s pretty unlikely we would have ever found those but for the [digital imaging] system — and certainly would not have found those as quickly.”

The 2018 primary recounts

Most important, the images were used to resolve close races where recounts were either required — due to the narrow margins — or requested by candidates. Maryland had four such recounts during its 2018 primaries. There, the state Board of Elections gave the campaigns a tutorial on using the ballot image database and access to the system. The election officials did not interpret the raw data. As a result, some candidates narrowed down their request for what precincts and ballot categories would be recounted using additional auditing protocols — which local election officials then followed.

“It’s intelligence. It’s data,” said Montgomery County’s McLaughlin. “Our whole legal and regulatory structure is designed around the handling of documents. You recount ballots or you don’t recount ballots. You audit a collection of physical documents, a collection of physical records. This ability to drill into and out of partial images, and then zoom into the larger image, it gives you this opportunity for the human brain to connect dots and tell a story and see patterns.”

McLaughlin, who described herself as an “election geek,” said the images raised all kinds of issues that state legislators eventually would have to sort out — because they broach the legal issue of a voter’s intent, and that, in turn, can raise questions about how the most poorly marked votes are to be counted or set aside.

“This all leads to questions of voter intent,” she said. “I can sit there and look at this universe of potential voter intent questions, but what do I do with them? How do I procedurally go about saying that this software is cluing us into a question that we investigate when, how and where? It’s in this world of subjectivity.”

Indeed, voter intent with sloppily marked ballots almost always surfaces in recounts where opposing candidates are throwing all the legal firepower they can muster at each other. Nonetheless, these high-ranking Maryland election officials were convinced that it was unambiguously positive for candidates to look at ballot images and decide whether and where to prioritize recounts — at least until legislators create new standards.

“It’s good for the candidates to be looking at this data. I don’t know how they are then using that information to decide whether they want to recount precincts,” McLaughlin said. “It’s fascinating. This is developing. We’re figuring these things out.”

Verifying the 2018 midterm vote

Right now, Maryland is the only state using Clear Ballot’s digital image audit software for all of its jurisdictions in November. (Vermont also uses the software, but it verifies results in a half-dozen towns after each election—a fraction of its municipalities.) Several large counties in a handful of western states and Florida are also using the software, Clear Ballot spokeswoman Hillary Lincoln said. The software can import, read and analyze the image files created by any commercially available ballot scanner, she said.

But the relatively limited deployment of this breakthrough technology is why vote count transparency activists like Audit USA are using provocative means — posting ES&S scanner manuals online — to draw attention to power and promise of ballot images to help verify vote counts. They have met with officials in Virginia, Florida, Maine, Michigan and California to urge them to create and preserve ballot images this fall. (This scanner software feature has to be turned on.) They have had mixed success on that front.

In the meantime, if you look at the ES&S website, that large voting machine and software maker is not touting transparent ballot digital image technology. Instead, it’s pushing new products where voters’ choices are printed in bar codes and other opaque formats like QVC codes for verification. (ES&S would not comment for this report.)

That commercial competition and less transparent approach, which contrasts with what Maryland is doing, reveals where the election transparency battle is heading after 2018’s midterm elections. State and local election officials can embrace a new generation of transparency and trust-generating tools, or they can obscure the vote-counting process, which some officials have said they want to do to avoid post-election litigation.

But that stubborn response, apparently encouraged by industry giants like ES&S, will only empower those who seek to undermine public confidence in elections by claiming that votes and elections are being stolen, and get away with that assertion because the evidence trail of the actual votes cast is not available or understandable.

“I’m an election geek. We are all election geeks here,” said McLaughlin. “We want to dig into this data and see what it tells us. Given the roughly two-week period that we have [to certify results], it doesn’t give us a huge amount of time to go digging and exploring and finding patterns and asking and answering questions. . . As election officials, we all love redundancies, too. It’s another data source to go back to in the event there is a challenge or a question or a concern, especially with paper ballots.”

Also Available on: www.salon.com