August Elections Improve on Spring Primaries, But Fall Worries Loom

After disastrous primaries in the early days of the pandemic, some of the same states have run better elections in August as voters have cast record numbers of mailed-out ballots and many in-person polling places reopened in metro areas, even though the same states’ COVID-19 rates are now higher.

This rebound contrasts with headline-dominating worries that are beyond the control of local officials who actually run elections. Those include deepening Trump administration interference with timely postal delivery of absentee ballot applications and the ballots themselves, and senior Republicans issuing orders that prevent sensible steps to help voters such as widely deploying ballot drop boxes.

The foremost example of a 2020 turnaround may be Wisconsin. Its August 11 local elections were the state’s next contest after April 7’s fraught presidential primary. April’s election was marred by a confluence of factors: last-minute partisan battles and court rulings about holding the election, abrupt poll closures in Wisconsin cities, and long lines and delays for many non-white voters who risked their health to vote.

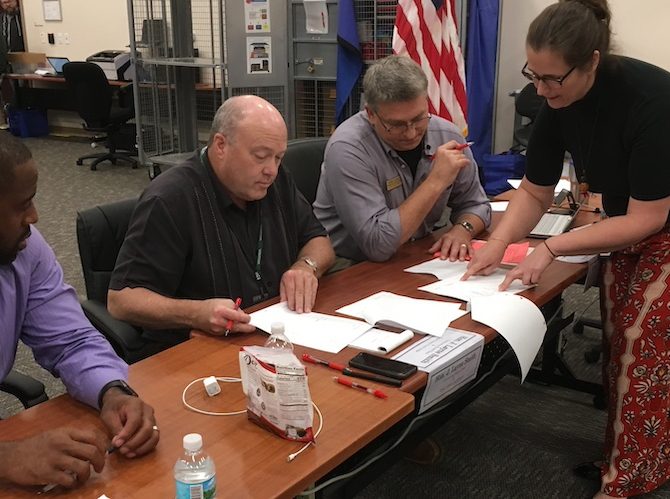

Even though August’s election was a low-turnout event where two-thirds of votes were cast on mailed-out ballots, Wisconsin officials instituted many changes with an eye to higher turnout this fall. In-person voting that was shut down in April was resurrected. Polling places were set up with social distancing measures, including curbside and other outdoor voting options. Voting rights activists praised these steps, even as they cited other concerns about casting votes that will count.

Across “most of the state, what we are hearing is the polling places have been set up very appropriately, given the pandemic,” said Debra Cronmiller, president of the League of Women Voters of Wisconsin, at an Election Day briefing from the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, a national advocacy group that runs a toll-free hotline to assist voters. “In Milwaukee, some signage for curbside voting was not clear for voters,” she said, adding that issue was soon fixed.

“I saw a lot better preparation,” said Kevin Kennedy, who oversaw Wisconsin’s elections from 1982 to 2016 as executive director of the Wisconsin Government Accountability Board. “All the polling places I visited [on August 11] were well set up. In Madison, almost all of them had the opportunity to vote in a drive-through situation or vote outdoors if you wanted to.”

One of the mistakes made by many states this spring, including Wisconsin, was assuming that voters would easily shift to voting with mailed-out ballots and not want to vote in person. For many reasons—staffing shortages, health concerns—urban clerks drastically reduced the number of polling places. However, many voters, especially in communities of color, wanted to vote in person, fueling the lines. Many voters said that they wanted to see their ballot cast and accepted.

Wisconsin took steps to revive in-person voting for August’s election. In Madison, the state capital, Kennedy said that polls had greeters and extra face masks for voters, and were overstaffed so “people have some experience before November.”

Cities that opened a handful of polls in April were headed back to normal, Kennedy said. Milwaukee, which in April only had five voting sites, had more than 160 polling places open, he said, adding that the city has a new election director. In Green Bay, which had two polling places open in April, 17 sites, about half of normal, were open, he said, noting it, too, has a new election director. Kenosha, the state’s fourth-largest city, had 30 polling places open.

Kennedy’s assessment, like that of the Lawyers’ Committee, was not worry free. But he was focused on how clerks were adjusting to the pandemic, whereas the League’s Cronmiller was more focused on how the process was working for voters.

Statewide, 900,000 voters requested absentee ballots for August’s election, according to state officials who said that two-thirds of those ballots were returned by Election Day. In April, 1.3 million absentee ballots had been requested. Because voting via mail ballots on that scale is new to Wisconsin, Cronmiller said that there was some confusion about how voters were supposed to return ballots in person on Election Day.

“We have had a little bit of confusion, especially in the Milwaukee area, about how to bring the rest of the uncast absentee ballots to the polling places,” she said.

Wisconsin has 1,850 voting jurisdictions. Most are small townships. The biggest cities, including Milwaukee, have slightly different rules than the rest of the state. One difference is where absentee ballots can be returned on Election Day.

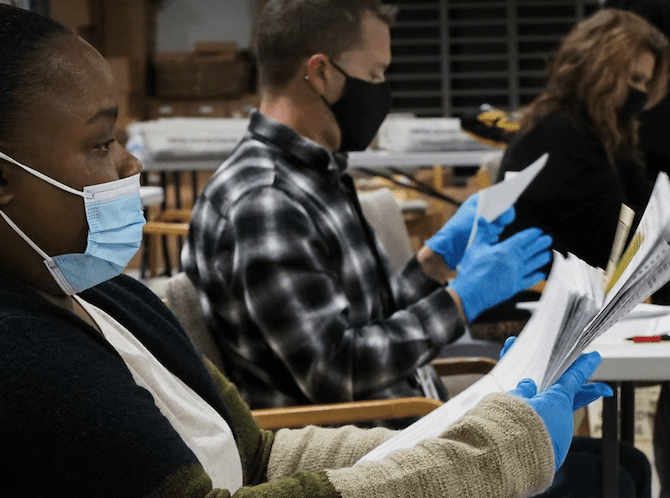

Like 35 other populous municipalities, Milwaukee has a central counting center for absentee ballots. State law says that the voters in these districts should return their absentee ballots directly to the counting center, city hall or clerk—but not to local polls. Elsewhere in the state, voters can return their mailed-out ballots to polling places, where they are equipped to count them.

Before the expansion of absentee voting, the issue of where to return absentee ballots was not a widespread concern, as only 6 percent of the state voted via mail ballots in 2018. However, many Milwaukee voters who had yet to return their ballot did not know what to do and took their ballot to a poll, Cronmiller said.

“People are trying to bring their uncast absentee ballot to the polling locations and are being directed back to the central count location,” she said. “There were some polling places that were accepting the absentee ballots, and they will have a courier bring the ballots to one of the counting locations at the end of the day.”

That lack of uniformity could pose legal issues in November, if Republicans file suits saying that all of the ballots weren’t treated equally—which was an issue in Florida’s 2000 presidential recount.

Kennedy noted that Wisconsin law allows voters to surrender their mailed-out ballot at the city’s polls and then vote with a regular ballot if they don’t want to deliver their ballot elsewhere. It was unclear whether Milwaukee poll workers were offering that option to these voters.

Kennedy estimated that the fall voter turnout would reach 70 percent. Of those voters, he said that about 60 percent would cast absentee ballots, meaning that polling places used on August 11 would see their in-person voter traffic double. (That percentage could go higher if the White House is successful in slowing the delivery of absentee ballot applications and ballot delivery immediately before November 3 election. On the other hand, the state begins mailing out these ballots seven weeks ahead of Election Day—to voters who requested them.)

Kennedy’s biggest worry for the fall after seeing the August election is that local officials will be so busy focusing on logistics that they overlook assuring the public that it is safe to vote.

“There is not a consistent message being sent to voters about how to vote safely or that the [Wisconsin Elections] Commission or local officials are looking out for your safety so that you can vote,” he said. “They are getting attention for, ‘Okay, we sent [personal protective] supplies.’ ‘We are calling in the National Guard because there is a shortage of poll workers.’ ‘There are more polling places.’ But there is not a message that says, ‘We are working really hard as state and local election officials to provide you with safe avenues to vote—by mail, by early voting or in-person absentee voting [dropping off a ballot], or in person on Election Day…’”

“Election officials need to be able to say, ‘We got this,’” Kennedy said.

Reid Magney, spokesman for the Wisconsin Elections Commission, said the WEC was planning a public information campaign, including mailing out absentee ballot applications statewide and telling voters where they could return ballots. Avoiding the confusion seen in Milwaukee on August 11 was one of its aims, he said.

“There were no major problems, but there were some small ones,” Magney said. “Our goal is to learn from those small problems and make adjustments so those things don’t become big problems in November.”

Outside Wisconsin

One of the challenges with assessing how voting will unfold this fall is grappling with the reality that most states have slightly differing, or widely differing, rules governing the fine print of the process. While that makes it hard to generalize, August’s elections appear to have been better run than the presidential primaries that immediately followed the pandemic’s outbreak this winter.

In Arizona, where COVID-19 cases have surged this summer, past experience with voting by mail—including starting to process and count returned mailed-out ballots two weeks before Election Day—helped to avoid meltdowns in its August 4 primary.

On August 11, seven more states held local elections, including Georgia. Its June 9 presidential primary saw a catalog of problems in the metro Atlanta counties that were called another national example of how not to run a high-stakes election.

This August, local news reported that Georgia’s elections were not replays of June’s “messy primary.” But the media and voting rights activists still noted that there were issues with Georgia’s rollout of new voting machines, which confounded poll workers and delayed voters—especially in urban communities of color.

The Lawyers’ Committee’s briefing cited the voting machine problems in several counties. At the start of the day, for example, some poll workers could not program cards that retrieved the correct ballot on a computer voting station. At the end of the day, several counties and the city of Macon had to extend poll closing times.

Election protection activists said the August election was nominally better than June’s. But they were hesitant to draw wider conclusions about preparations for the fall.

“The turnout was so low that you couldn’t tell if it was going to be better,” said Helen Butler, who heads the Georgia Coalition for the People’s Agenda. “We didn’t have long lines. We didn’t have as many issues. But there are still issues like, for instance, absentee ballots not being processed smoothly.”

“These [ballots] weren’t coming from the vendor in Arizona,” she said, recounting one cause behind the delivery delays in June. Yet it took one of her relatives 13 days to get an absentee ballot in Fulton County, in metro Atlanta, for August’s election, which was a relatively low-turnout contest.

“There should not be that long of a time,” Butler said. “In fact, they got their ballot the day before Election Day. And we dropped it off in the drop box, so we will see about their drop box process: how that works. Or whether they will get a letter, like some people got after the last election, saying their ballot didn’t count.”

“There still are some glitches out there,” she said. “Not quite as many [as June], but there still are glitches that we hope will be worked out for November.”

Georgia officials have been making some adjustments before the fall, including tacit admissions that the number of presidential votes had been undercounted.

On August 10, the Georgia State Election Board admitted that scanners failed to count votes in June because their software settings were set too high, said Garland Favorito of Voter GA, which advocates for verified election results. The automated settings assess if a ballot oval has been sufficiently filled in by a voter. Voters who checked a bubble, as opposed to filling in the ballot oval, were not counted. The board ordered the settings to be slightly lowered for November, Favorito said, but the new threshold will not be as forgiving as in other states using the same system.

In other news that frustrated advocates, the state announced that voters will be able to use a soon-to-be-launched online portal to apply for an absentee fall ballot. (The current portal requires voters to download, print, sign and return the application.) In contrast, applications were mailed to all active voters before June’s primary.

Stepping back, August’s elections show that local officials are adjusting to holding elections in a pandemic. Yet these recent elections also underscore that introducing changes in the voting process are often confusing for all involved—and that is before partisan considerations enter the equation.

Also Available on: www.alternet.org