The Midterm Election is Over, But Stolen Election Conspiracies Remain

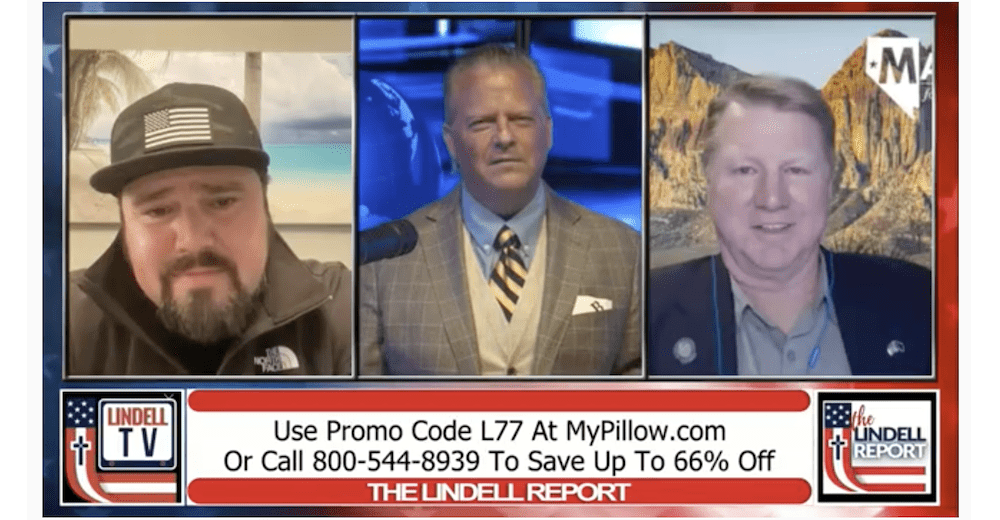

(Image: Robert Beadles, at left, and Jim Marchant, at right, on The Lindell Report on Dec. 13, 2022.)

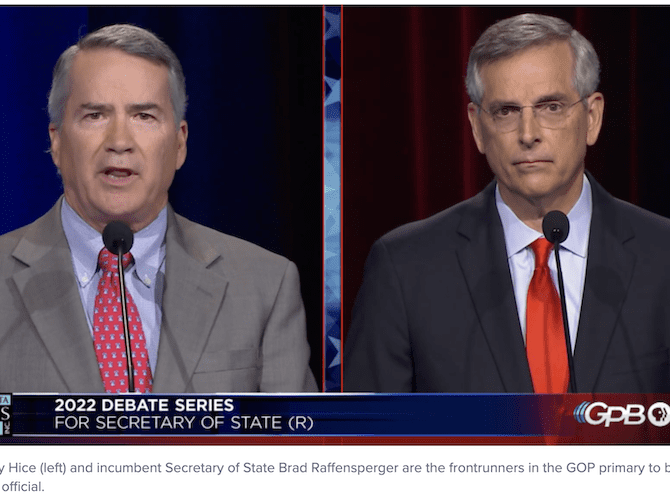

Republican candidates for governor, secretary of state and attorney general who denied the results or the legitimacy of the 2020 presidential election were widely rejected by battleground state voters in 2022’s general election. But those results have not put stolen election conspiracies to rest nor silenced their promoters.

The multi-faceted narrative of massive illegal voting, voting rules changes favoring one party, and secret software that can reassign votes has resurfaced in election challenge lawsuits, fundraising pitches, and pro-Trump media with a new twist. Debunked falsehoods about 2020 are not just being portrayed as fact, but they are being cited to contend that many of 2022’s top races were similarly stolen.

“Our election system throughout the country is compromised and we got to do something about it,” said Jim Marchant, who ran for Nevada secretary of state, led a national coalition of election-denying secretary of state candidates, and on Tuesday told The Lindell Report broadcast that he lost in November only after 170,000 voters were switched in Clark County, where Las Vegas is located.

“Once again, the ’22 election proved they’re doing the same thing they did in ’18 and ’20, and certainly 2022,” Marchant said.

The persistence of election conspiracies in pro-Trump circles will shadow 2023’s state legislative sessions and American political culture where a lingering distrust of election officials, voting systems and results have led to a loss of confidence in elections and has led to threats against state and local officials.

Nationally, nearly 180 election-denying candidates for federal and state office were elected in November’s general election, according to the Washington Post. The professed beliefs in untrustworthy elections already has led to a new round of 2023 state legislation to winnow voting options and to newly police various stages in the process. (A pending Supreme Court case could lessen the judiciary’s check on new voting laws, from gerrymanders to access to a ballot.)

The election-denying arena has deepened in recent years and has not shown signs of going away, according to recent reflections by top state election officials.

“Right now, we’re talking about mis- and disinformation,” said Judd Choate, Colorado director of elections, at a Thursday webinar on model state responses to these narratives hosted by the University of Minnesota’s election administration certificate program. “But it is fair to say that this has metastasized into other things like threats against election officials and making our lives all much more difficult in things like open records requests and endless lawsuits.”

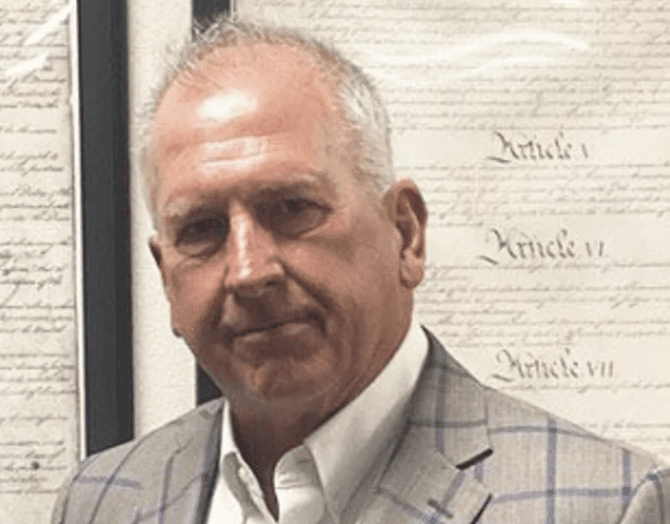

On Tuesday’s Lindell Report, Marchant was joined by Nevada businessman Robert Beadles, who, among other things, has offered a $50,000 reward to anyone who can “prove me wrong” that more than 170,000 votes were secretly switched in Clark County during 2022’s general election.

Beadles’ and Marchant’s claim was based on reviving a conspiracy theory that was debunked in 2020 involving two software programs called “Hammer” and “Scorecard.” The programs, which were patented in 2008 and 2009, theoretically can access blocks of votes in counting systems and can then alter results. In 2020, Trump’s allies claimed that the software was used to tilt the presidential results. However, the Trump’s administration’s top cybersecurity official disagreed.

“On allegations that election systems were manipulated, 59 election security experts all agree, ‘in every case of which we are aware, these claims either have been unsubstantiated or are technically incoherent.’ #Protect2020,” Chris Krebs, director of the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, tweeted in November 2020.

Nonetheless, Beadles and Marchant claim that the software had been used remotely to alter electronic vote counts in 2022 elections in Nevada and other states to the detriment of pro-Trump candidates. As “proof,” Beadles cited a 77-page statistical analysis that he said had found mathematical traces of the hack.

A Lindell Report host asked, “Where is this machine [hosting the software] running so that it can control all of these different outcomes?” Beadles replied that he did not know; the software “literally could be flipping votes from anywhere on the planet because everything is hooked up [to the Internet].”

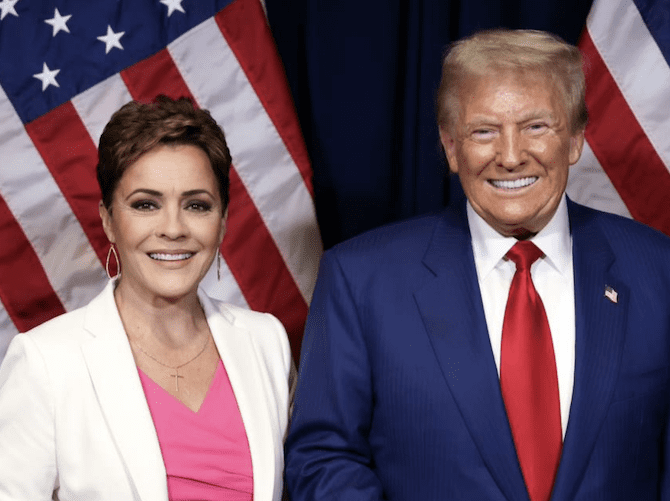

Beadles also recited allegations that are not new in pro-Trump circles, but which have appeared in recent post-2022 election lawsuits, such as Kari Lake’s lawsuit to overturn Arizona’s gubernatorial election where she lost.

Nevada’s voter rolls were “corrupt,” Beadles said. Its vote-by-mail system invited fraud, he said. Ballot-collection campaigns – “harvesting” – should be illegal, and signatures on ballot return envelopes were not properly vetted, he said. And after paper ballots were scanned and the electronic counting began, Beadles said that the “Hammer” and “Scorecard” secretly reshuffled votes.

“That’s where the old switcheroo happens,” he said. “And we can also prove, just in the last general election, that they stole 174,000 votes from Jim Marchant, just in one county alone. So, he is the rightful winner for the secretary of state, and, again, there’s a $50,000 reward out there to prove me wrong.”

On November 22, Nevada’s Supreme Court and its outgoing Secretary of State, Barbara Cegavske, a Republican, certified the 2022 general election results, which included Republican Joe Lombardo defeating Democratic Gov. Steve Sisolak. And other Nevada Republicans whose took public office after claiming that Trump’s second term was stolen, have attested to the accuracy of 2022’s results.

Nye County Clerk Mark Kampf, a 2020 election denier who was appointed last summer and elected in November, oversaw an unofficial hand count of 17,700 general election ballots. The hand count found that Nye County’s voting system computers, made by Dominion, had correctly read 99.87 percent of the ballots, Kampf said Friday.

The incorrectly counted 0.13 percent were votes where voters had sloppily marked the ballot. Dominion’s system did not count those votes until county election workers – with political party observers watching – looked at a digital image of the ballot (made by the scanner) to determine the voter’s intent. A second looked resulted in reassigning the sloppily marked vote.

“It was something that everyone needed to see,” said a Nye County clerk office employee, referring to the system’s accuracy. “There’s always a doubt.”

But Beadles, who is continuing to cast doubt on elections where his preferred candidates lost, keeps spreading misinformation.

“No human is verifying that the votes are legitimate,” he said Tuesday on The Lindell Report, where he made no mention of Nye County’s hand count.