Explaining a Likely Cause Behind Iowa’s Caucus Meltdown

The electronic system used by the Iowa Democratic Party on Monday night to compile its 2020 presidential caucus results was only counting “partial data,” Iowa Democratic Party chairman Troy Price said in a statement Tuesday morning, giving the most specific clue about what went wrong.

That partial data—called a “coding error” in the most recent national press reports—was most likely tied to three different sets of figures that the IDP planned to release for the first time after the caucuses ended, but withheld due to what the IDP called unspecified “inconsistencies.”

The state party announced at midday that the “majority” of results will be released at 4 PM Central Standard Time.

Those three sets of “inconsistent” figures — details of which the Iowa party has never released in previous cycles — could only refer to steps in the process where the number of participants and the votes cast in two consecutive rounds of caucus voting did not all match.

Iowa Democratic officials haven’t said more yet about what went wrong with the tabulating system software, which was never tested before on the scale used Monday. evening But it is possible to identify one discrepancy in the numbers that would have been reported via the IDP’s app to its software and system and could have caused the “partial” data and “inconsistent” analyses.

A likely cause of “partial data” flaw may have been the process itself, according to my own eye-witness observations and assessment (based on undertaking Iowa’s caucus chair training and numerous interviews with top party officials, including a demo of the app last week).

The “partial data” or data mismatch may have little to do with the app used by caucus chairs to report the winners in two consecutive rounds of voting and the resulting delegate allotments (although caucus chairs and campaign precinct captains had problems with getting online and logging into systems.) A more likely problem was simply that not everybody attending a caucus voted in the second round, if their top presidential choice was disqualified in the first round.

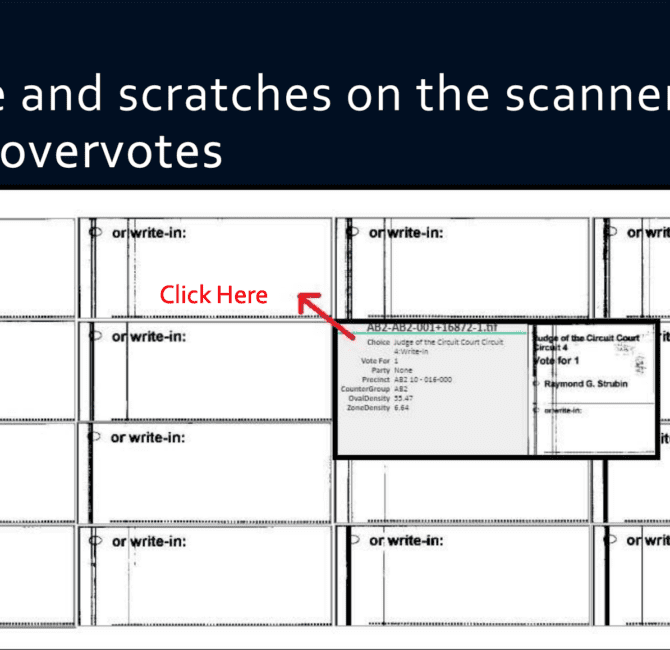

That pattern of drop-off voting could have produced the “inconsistencies” that were seen by the IDP boiler room. In the demo by Iowa Democratic Party executive director Kevin Geiken, the app showed when too many participants went into its calculator (called an “overcount” on the app), but it didn’t report undercounting or intentional drop offs in the second round.

This very scenario was seen in Polk County’s 57th precinct in Des Moines, when 11 voters of the 385 attendees did not vote for another candidate in the realignment round—after their first presidential choice was eliminated.

Those voters mostly came to vote for Joe Biden and were overheard saying that they could not vote for anyone else, especially after the race’s other centrist, Amy Klobuchar, also had been eliminated in the qualifying first round. They didn’t want to cast a vote for Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren in the realignment.

In other words, they came and they voted. Their first choice lost, or at least wasn’t “viable” in that room. They didn’t pick another candidate. Thus, there were gaps between the number of participants in the two rounds of voting. That could account for tabulation software in the IDP’s electronic backend seeking balanced totals — via an app on each of 1,678 chairs’ smartphones — and reporting figures that didn’t match or balance out.

Or these same voter fall-off numbers also could have appeared in called-in results that the state party was receiving, if the caucus chairs could not connect with their app to the party’s backend. That also happened in Polk-57, where Caucus Chair John McCormally could not get his app to log in before and during the event, despite trying several times.

So McCormally ran the caucus using pens, math, and paper, and then called in results. In his case, McCormally reported the results quickly (possibly because his wife was a volunteer there). But other chairs across the state encountered waits of 90 minutes before talking to the party

This quagmire deepened inside Democratic Party headquarters when it had to assess the growing problem. They had to quickly find a solution or use a backup plan, which top party officials had bullishly predicted only a day earlier that they would not need. The backup entailed gathering from every caucus chair the paper summary sheets that list the voting round totals and delegates won.

The summary sheets, signed by precinct captains from all the campaigns, were to be turned in to Democratic county chairs (along with presidential preference cards filled out by voters), according to the caucus training materials. The county chairs, in turn, were to turn in all their paper records to Iowa Democratic Party headquarters either in person or by mail.

Before Caucus Night, Geiken was asked about worst-case scenarios in a demo of the caucus app that only two reporters attended—including this writer. It might take a day or two to physically collect and recount the full paper vote record, should the electronic system be jettisoned for whatever reason. He emphasized there would be a reliable and accurate count, but it might not be as fast as expected.

The state party’s announcement early on Tuesday that the “majority” of votes would be released suggests that it made a dash to collect and count as many ballot summary sheets as possible.

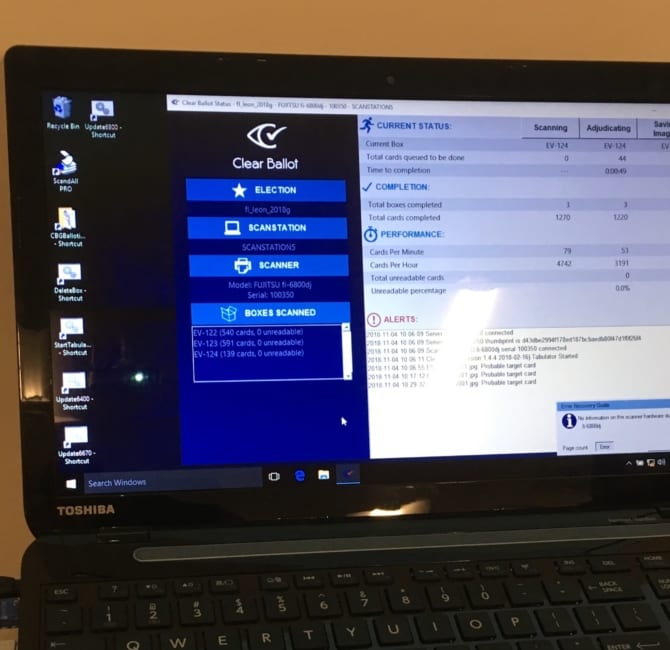

When I covered this ‘what comes next’ scenario before Iowa’s caucuses, few state and national party officials imagined that the reporting system would melt down. They expressed great confidence in the party’s voting system and its private contractors. (Caucuses are not run directly by government election officials but use rented voting systems.)

Even hours before the caucuses began, these officials downplayed reports that some precinct chairs were having trouble signing onto the caucus app, as well as the possible consequences.

But voting technology experts predicted these problems. Reliability issues are to be expected when a new system debuts, especially one that has not been tested at scale and when its users encounter access issues (insufficient bandwidth and unable to log in) atop software glitches. That is why government election officials like to debut new voting systems in low-profile races.

Iowans and everyone else will get to see accurate results eventually. That is a silver lining. The IDP will be using a paper trail and that paper trail will be more detailed than in any past caucus.

The only other silver lining might be the realization by national media outlets that it may not be possible to report fast and accurate results on election nights. Many other states will introduce new voting and reporting systems in caucuses and primaries this year. But Nevada, at least, has abandoned a system similar to the one that crashed in Iowa.

“Nevada Dems can confidently say that what happened in the Iowa caucus last night will not happen in Nevada on February 22nd,” said Nevada Democratic Party Chair William McCurdy II on Tuesday. “We will not be employing the same app or vendor used in the Iowa caucus. We had already developed a series of backups and redundant reporting systems, and are currently evaluating the best path forward.”

Also Available on: www.nationalmemo.com