Georgia’s Top Election Official Draws Praise for Defying Trump, But His Minions Run Presidential Audit with Heavy Hand

(Photo: Steven Rosenfeld)

(Editor’s note: This report has been updated.)

Outside of Georgia, Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger is seen as a rare Republican willing to defend his state’s elections against attacks from President Trump and his base after Joe Biden won the Georgia election by 14,000 votes. But the view from the ground is not as clear as the state approaches a series of key deadlines this week, starting with a manual audit of nearly 5 million presidential ballots by Wednesday at midnight and certifying the results by Friday.

(Late Thursday, Raffensperger announced that the audit confirmed Biden has won the state’s presidential election by 12,284 votes, out of nearly 5 million presidential votes cast.)

Raffensperger ordered the hand count last week as his interpretation of what a 2019 election audit law required. He quickly came under attack from fellow Republicans. The state’s two U.S. senators, both facing runoffs that could decide that body’s majority, demanded that he resign. Trump supporters who became observers at counting centers attacked the audit as dishonest, taking their cues from Trump’s tweets and Fox News. On Friday, South Carolina Sen. Lindsey Graham asked Raffensperger if he could disqualify enough votes so Trump would win.

These pressure tactics, especially Graham’s gambit, kept making headlines into this week, even though Republican extremists known for pushing the myth of rampant voter fraud—the group TrueTheVote—reversed course on the same ploy in Michigan on Monday. They withdrew their lawsuit seeking to disqualify all the votes in three counties, enough votes for Trump to win.

Despite praise from afar, Raffensperger and his top lieutenant, election operations manager Gabriel Sterling, have not been entirely angelic with their handling of the almost-completed hand count of Georgia’s presidential votes. As that process has unfolded, both have spun their own conspiracy theories surrounding potential Democratic interlopers in the upcoming U.S. Senate recounts (which could decide its majority). They repeatedly have threatened to imprison anyone who comes to Georgia to fraudulently vote. Sterling also keeps saying he expected instances of fraudulent voting to be found, although he has not released any evidence of illegal voting.

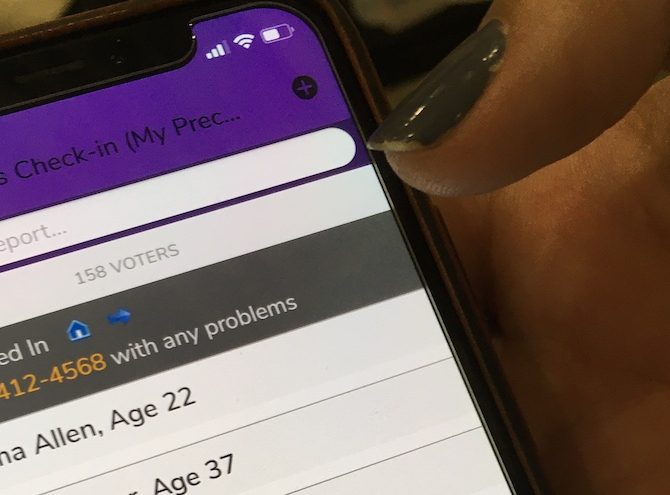

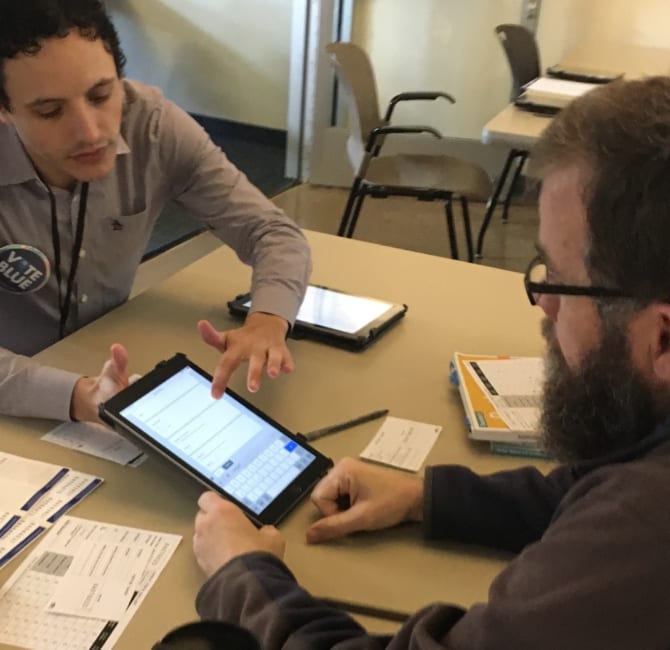

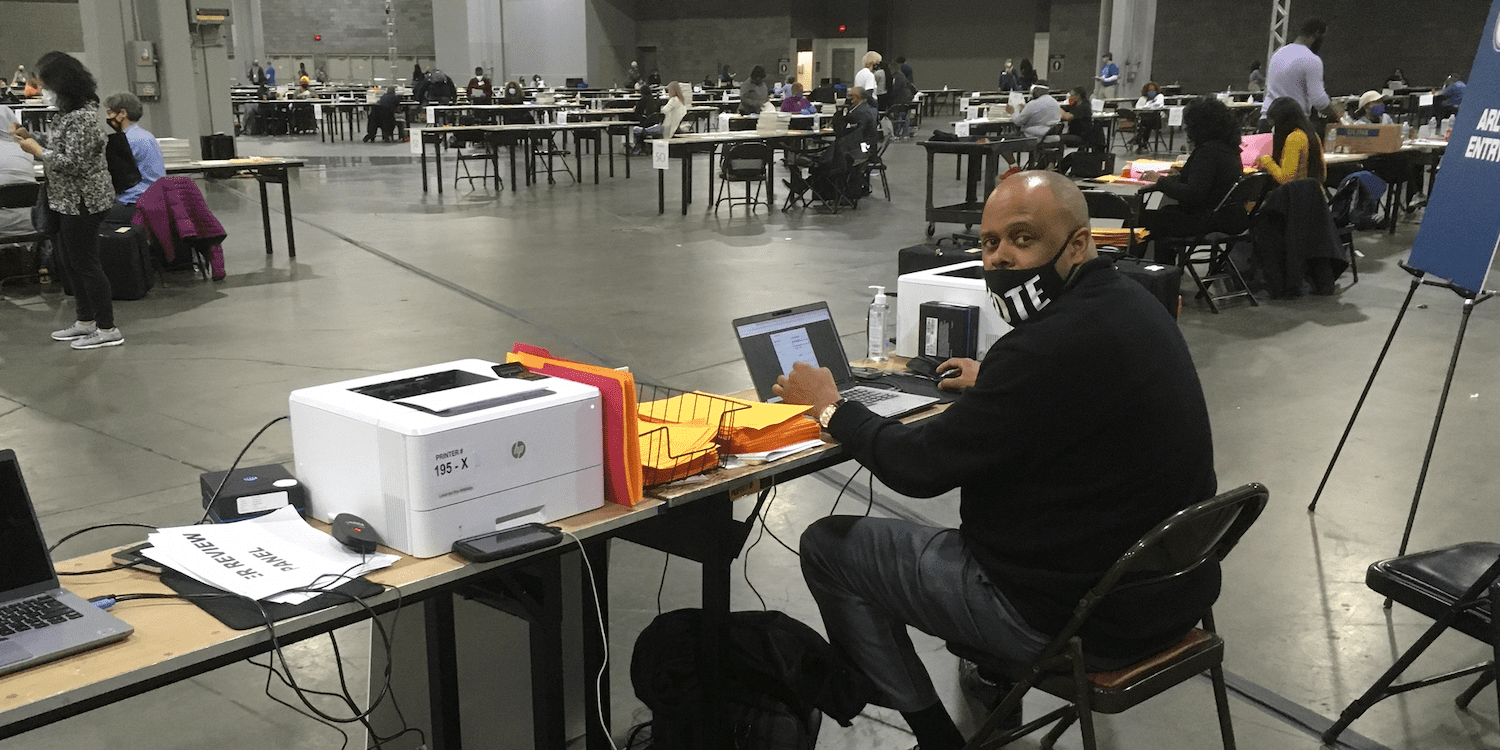

The hand-count audit’s particulars have also drawn little scrutiny. Instead, a new daily ritual has emerged. The two men have held near-daily press conferences (first on statehouse steps, now on zoom due to COVID quarantines), where reporters from near and far keep hearing how the secretary is following the state’s new audit law. The required “risk-limiting” audit is intended to assess the accuracy of the first unofficial results before certifying election winners.

Sterling has presented a tight narrative. He has repeatedly attacked county election officials for “managerial” lapses, as the audit found several thousand uncounted votes in several counties. In most of these instances, officials apparently did not use the state’s voting system properly, he said. In one county, ballots were set aside and were not counted. In another, votes recorded on thumb drives were not sent to the central counting system. After disclosing these findings and noting “nothing indicated it changed the outcome of the vote,” Sterling said the results from “many counties are… spot dead on.”

There’s some reason to believe that last claim, which suggests the machinery never errs while humans do, was not entirely true. Reporters could not take as close a look at the hand count as political party observers. While most pro-Trump observers were grousing about the election’s results and looking suspiciously at everything, there were a few observers in Georgia (with Libertarian credentials) who have spent years studying audits in other states.

Colorado activist Harvie Branscomb noticed that the vendor running the audit, California-based Voting Works, had only set up one computer work station in each county’s counting center. The station was to be used to send the totals of every hand-counted batch of ballots to the secretary of state, whose staff was compiling the results. Branscomb noted it was inconsistent to rely on software used behind closed doors in an exercise that was touted as a hand count in the open. He also worried about data-entry typos at those computer stations at county voting centers and was told that the software was rewritten in the middle of the audit to speed its processing time.

More curious was what he saw in Cobb County near Atlanta, which duplicated 5,000 hand-marked absentee ballots. Why were they duplicated? Because local officials turned off a feature on counting scanners to flag poorly marked ballots, he was told. (Activists who have sued the state over its new voting technology have said the scanners can miss lightly marked ovals on paper absentee ballots). That was a voting machine performance issue—not hacking, a planned cyber-attack or “managerial” incompetence.

Most eye-opening, however, was Branscomb’s discovery that county officials may have found a way to not report small errors to the Sterling and Raffensperger. The officials were told to use the state’s computer link to report their results from every batch of ballots. Branscomb said that some counties appeared to be comparing their hand count results to their electronic totals from Election Day before submitting their ballot batch data to the state—to spot inconsistencies and reconcile their figures. Doing so would muddy any audit process, especially a statistic-based audit that relies on a fixed data set (the number of ballots and initially reported results).

What are we to make of details like these? They show that running elections are more complex than watching election workers count ballots by hand. These complexities reveal how stressful the process can be, and how political considerations come into play.

One election recount lawyer thought the full hand count was a shrewd move by Raffensperger. While it didn’t deflect criticism from fellow Republicans, it was a non-adversarial process that ran out the clock as court battles over the presidential results in other states played out (with Trump losing most). A recount, in contrast, was a different legal process and allows opposing candidates to contest ballots. Trump can still file for a recount in Georgia after its results are certified. The certification deadline for Georgia’s general election is Friday, November 20.