Many New Voting Systems Debuted in 2020 Aren’t Ready for Prime Time

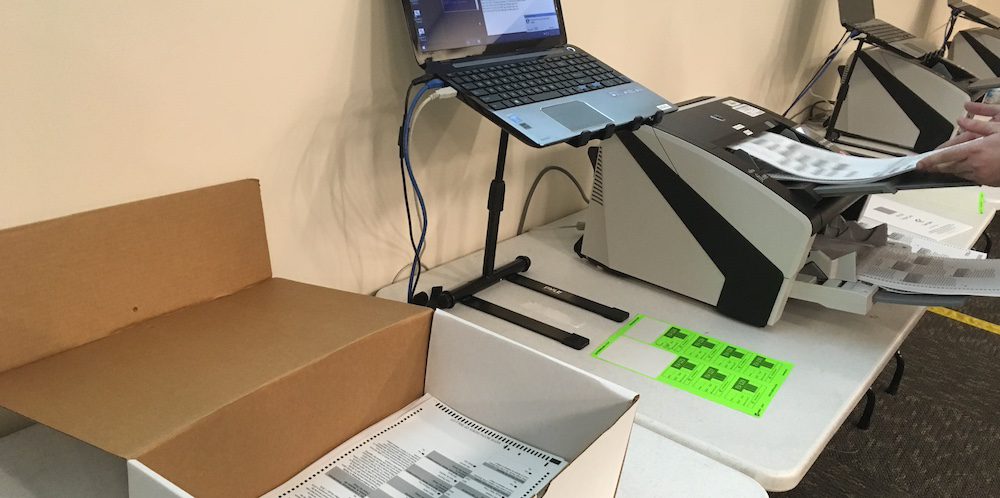

(Voting system technology. Photo by Steven Rosenfeld)

Put aside, for now, foreign meddling in U.S. elections, social media propaganda and partisan voter suppression. The newest emerging threat to elections in 2020 is new voting systems that have been insufficiently tested and phased in, but have been debuting in many of 2020’s presidential primaries and caucuses.

Since the Iowa Democratic Party’s presidential caucuses, there has been a string of new technology-based failures and frustrations—despite officials’ and voting system designers’ intentions. The failures share some common elements, from data connectivity issues to machinery breakdowns to poor planning—whether in party-run or government-run contests.

While some defenders of the newest systems praise efforts to counter cybersecurity threats since 2016’s Russian hacking, what is indisputable is that 2020’s opening contests have been marred by hours-long delays, malfunctioning machines and counting issues, frustrating voters, poll workers and campaigns.

The problems are wider and deeper than has been acknowledged. Unless steps are taken to understand what failed and address causes, they could recur in the fall’s even-higher-stakes elections, when the voter turnout will likely be double or more than early 2020’s nominating contests.

After Iowa, Media Silence

Voting Booth has witnessed problems in many early nominating contests. While elections always have snafus, the year has not had a good start as various problems have affected large numbers of voters.

Not only were Iowa’s results delayed for more than a day, but 10 percent of precincts there also apparently filed inaccurate tallies. In Nevada’s Democratic Party caucuses, thousands of early voters waited for hours. Its reporting of results took longer than Iowa because of vote-counting data problems. Meanwhile, 9 percent of Nevada precincts also apparently filed inaccurate tallies.

However, unlike Iowa’s photo finish where participants were demoralized by inconclusive results and many in the media voiced anger at officials, in Nevada the coverage mostly focused on Bernie Sanders’ landslide win. In later primaries, the press has similarly focused on the shrinking field, not the voting process. But problems with new voting systems did not vanish.

In one of South Carolina’s three metro areas, surrounding the state capital city of Columbia, its Democratic primary saw one-in-six new machines—automatically marking or scanning ballots—malfunction or jam.

In Los Angeles County, the country’s most populous election jurisdiction, voters waited for hours after work on Super Tuesday. California’s statewide voter database—used to check in voters—had connectivity issues, was slow, and intermittent in 15 counties. Los Angeles’s new publicly owned system, which had positive aspects such as multilingual ballots and allowing voters with mail-in ballots to cast new ballots after candidates dropped out, saw one-fifth of its ballot-marking devices fail. Needless to say, the long waits and machine failures quickly overshadowed the positive features.

In Dallas County, Texas, it took officials several days to discover that 10 percent of Super Tuesday’s ballots went uncounted. Election Administrator Toni Pippins-Poole found 44 thumb drives—which store the tabulation data for each precinct—were not included in the official results. Despite criticism about her office’s handling of its new voting system, she has sought a court order to conduct a manual recount. (In Harris County, where Houston is located, partisan allocations of voting machines led to hours-long waits.)

Problems Seen, Solutions Harder

Not all of these mistakes are minor or easily rectified. They have different causes, including technological breakdowns, training lapses, unfamiliarity with new systems by election workers and voters, and human errors—such as data-entry typos when handling vote-count data. The causes can cascade and affect close contests. They also can undermine public confidence.

It may not be fair when one aspect of a complex system fails and the entire enterprise is tarred. However, high-stakes processes like voting have little margin for error. This is why 2020’s voting system debuts are troubling.

Unless solutions are found and implemented—which is more easily said than done—it would not be hyperbole to suggest that more voters would have to turn out in the tightest fall contests (where new systems are being used) for one side to win. New technology that is now present, but not ready for prime time, could undermine voters and outcomes.

This scenario is not what election managers, voting system vendors and their defenders in the public policy arena have been saying after each of 2020’s fraught presidential contests. The quick retort from the newest system’s defenders is that Iowa’s and Nevada’s caucuses were amateurish party-run contests, while government-run primaries are more professional.

That line is a bit porous on closer examination, however, because some of the problems at the caucuses—device failures, scrambled data, poor online connectivity—have also surfaced in government-run primaries. Error rates of between 10 and 20 percent—in equipment malfunctions and counting—keep recurring. Unanticipated problems have surfaced with systems that have been hastily put together (the caucuses) or taken years (Los Angeles).

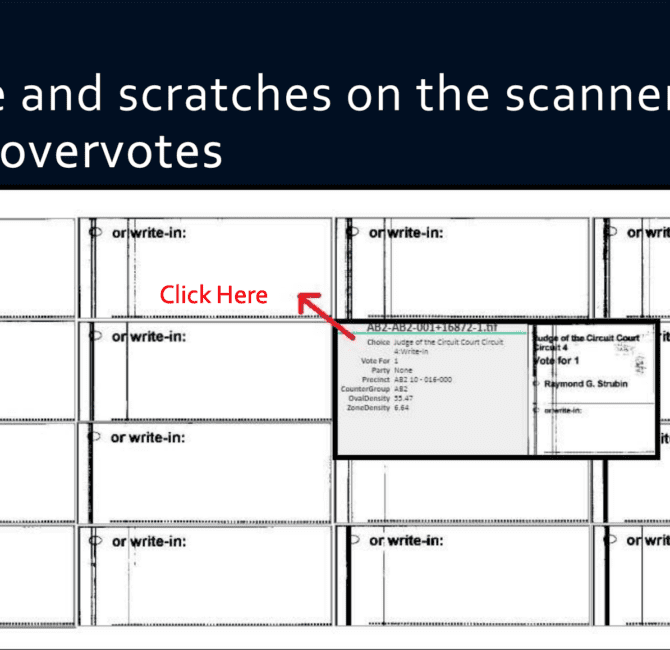

Running elections has never been easy. There are key decision points where the correct choices in technology and procedures help or impede the process. If one looks at what voting system elements have underperformed so far in 2020, some takeaways emerge. Needless to say, new machinery should not fail in large numbers in its first major debut. Examining the event logs on those machines should reveal what happened—as opposed to speculating.

While it also appears that there have been no cybersecurity breaches thus far, election officials’ post-2016 focus on cybersecurity may have distracted from planning surrounding the more mundane, human aspects of voting. They assumed new equipment would work and voters would quickly adapt to new poll locations, early voting, new check-in procedures, new balloting and more.

Voters don’t expect their elections to be hacked. Nor do they expect to wait for hours, see iPads with registration files go down, see costly new ballot-marking devices fail, see paper ballots clog new scanners, and not get honest explanations from officials about what is happening.

If these frustrations seem like griping or expecting too much, the question of “how good is good enough?” will likely resurface again in November. Should officials be unable to show that the process was trustable and the results accurate, the stakes will be much higher than they are now.

Also Available on: www.truthdig.com