New Technologies Could Actually Eliminate Common Voting Controversies in the U.S.—And May Put a Stop to Fear and Paranoia Around Election Counts

As voting in 2018’s midterms ends on Tuesday, November 6, there will be contests with surprising results, races separated by the slimmest of margins, or even ties. How will voters know what to believe without falling prey to partisan angst and conspiracies?

What if, as Dean Logan, Los Angeles County’s voting chief, retweeted this week, “the weakest link in election security is confidence” in the reported results?

The factual answers lie in the voting system technology used and the transparency—or its lack—in the vote counting, count auditing and recount process. These steps all fall before outcomes are certified and the election is legally over.

Seen nationally, the U.S. in 2018 is mostly voting on paper ballots that are counted by electronic scanners. That creates a spectrum of possible evidence that can be closely examined in 36 states—from individual ballots themselves, to digital images of the ballots, to spreadsheets of every vote, and more.

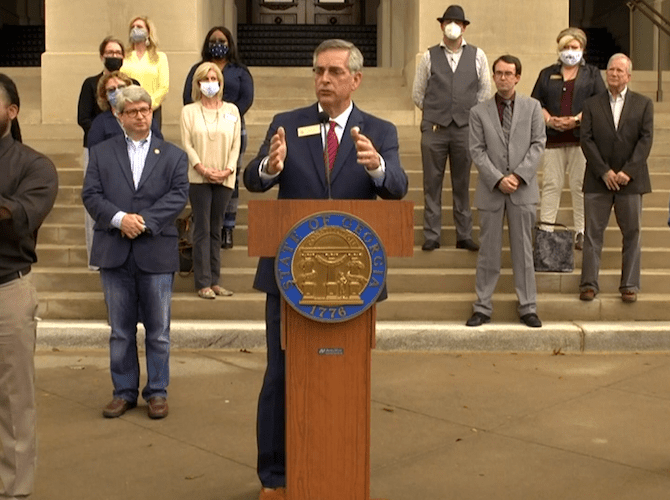

Some states, led by Georgia, resist this nuanced scenario. There, most people will vote on dated electronic machines where whatever is captured on computer memory cards will be the vote record, although its mail-in and provisional ballots are paper, and thus could be more closely examined. (This is where post-election legal fights would be.)

How well will election officials—from civil servants to poll workers—manage 2018’s growing rivers of paper ballots? How accurate will ballot scanning be? How much double-checking is possible, given new technology and audit techniques? These questions and answers will likely emerge in some high-stakes contests, as well as whether these tasks are being done transparently and can be easily understood.

Most states and counties will not be experimenting with the newest vote counting technology. Yet a handful will be using two important new techniques that should be heeded for high-stakes reasons. In the short run, these approaches may decide 2018’s winners. Down the road, their use will expand for 2020’s elections. And they will influence at least 33 states that say they will be buying a new generation of voting systems before the next presidential election, which, in turn, will determine how transparent and trustworthy America’s vote counts will be for years to come.

Two Approaches, Two Camps

Proponents of the two most promising new vote verification tools—“risk-limiting” audits and “digital ballot image” audits—say each can inject an unprecedented sense of public confidence. Yet, ironically, within a small world of experts and entrepreneurs who have dedicated their lives to making vote counts more trustable, there are big disagreements over the pros and cons of each. So much so, that the foremost statistician behind risk-limiting audits this July lobbied a California commission to ban ballot images from the state’s double-checking, even though Maryland and some Florida counties prefer using the high-definition images of the ballot cards to verify their vote counts.

Nonetheless, these two approaches achieve very different goals. That raises questions of why more election insiders aren’t talking about their relative strengths—especially as the nation’s thousands of local election jurisdictions have different needs, equipment, staffing, budgets and technical fluency.

“I think you’re right. I think there can be, and there needs to be, kind of a nexus where all of these considerations—the Venn diagram of efficiency and security and transparency—come into play,” said Tammy Patrick, senior adviser for elections at the Democracy Fund, a new foundation-funded initiative. “I am hopeful that at whatever that meeting or juncture is, it leverages the technology that there are scans being made of the ballots, and it also leverages the ability that after reviewing any discrepancies—quickly within the images—that you can also compare a small sampling of them to a paper ballot, for instance. So that you still have the legitimacy and the ability to verify and validate the paper, but without having to do large volumes of it.”

Patrick, who ran elections in Arizona’s most populous county for 11 years, is pointing to the different steps in verifying vote counts involving paper ballots. First, voters make ink marks on the ballot cards. Those cards are run through the scanners at local precincts or vote centers. The ballots generally fall into bins in precincts, where they are jumbled. In larger vote centers, they can be more neatly organized by more modernized (and expensive) gear. Then the tabulation starts. Officials first check that the number of voters matches the number of ballots. Then the totals for each contest are compiled into what’s called a “cast vote record”—imagine a giant spreadsheet or grid, where the ink marks and blanks that are detected and counted by the scanners fill the cells as ones, zeros or blanks. That electronic worksheet allows officials to add up the vertical columns for the count.

The question then becomes: How do you know the ballot scanner’s count is correct?

Risk-Limiting Audits

In the past decade, two differing approaches to answering that question have emerged and evolved. The first to surface is what’s called a risk-limiting audit (RLA). Jerome Lovato, now an election technology specialist with the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, was present at the start of developing and implementing RLAs a decade ago when Colorado hired him to improve their audit process. Colorado had been sued for a lack of transparency surrounding its testing and certification after buying new machines in 2006. Back then, Colorado—like many states today—grabbed and examined hundreds of ballots after every election to see if they matched the announced winners.

“We were looking at something more statistically based, that said, ‘Did the winner win?’ ‘Did the loser lose?’ And providing that statistical confidence to the public,” Lovato said. “And that also gave us what we didn’t have, which was what happens if we have a discrepancy. Because the way we did audits before, a county [office] would say, ‘We have a discrepancy. Our counts aren’t matching. We ran 150 ballots and our hand count says 149 and the machine says 150.’ We [the state] would say, ‘Okay, try it again. Do it one more time. Make sure the hand count was accurate, because that always tended to be the case…’ But we didn’t have any kind of calculation that said, ‘Look at X-percentage more ballots’ or anything.”

That void and guesswork was filled by what’s now called a risk-limiting audit. While there are several ways to do these, the basic idea is that it is statistically possible to randomly count a small number of paper ballots—if all of the ballots have been carefully handled and assembled (a big if)—and determine with 95 percent probability, or more, if the correct winner was announced.

This past summer, Fairfax County, Virginia, piloted two types of risk-limiting audits in a race where 948 ballots were cast. In the first, it wanted 95 percent certainty the correct winner was chosen and, given the math, only needed to pull 69 paper ballots. That “ballot comparison” process assumed that all of the ballots were initially scanned, collected and compiled in a precise order—so they could be subsequently traced by individual ballot. That controlled environment mimics some vote centers—where people vote—or local offices that are central counting sites.

The second, a “ballot polling” audit, is designed to verify counts of paper ballots that fall as a disorganized jumble into bins below the scanners at local precincts. Seeking 90 percent certainty, it required officials to examine 260 unique ballots in its initial round. After pulling that many randomly selected ballots from their storage boxes and seeing how their ink marks compared to the reported outcome, the math found there was a “53 percent chance that the audit would have identified an incorrect outcome,” a Virginia Department of Elections report said. “In a true RLA, election officials would have selected a second round of sample ballots and completed the process again, repeating until either the risk limit was achieved or it was determined that there was a need to proceed to a full recount.”

In other words, when precinct voting is involved—which is the way most of the country votes east of the Rocky Mountains—double-checking the vote this way can be laborious, although somewhat more efficient than a full manual count, or reexamination, of every ballot. Virginia’s Department of Elections compared risk-limiting audits to political exit polls—where some voters are questioned to assert larger trends. It’s not a full accounting process. It is a statistical analysis to confirm, or question, whether the announced winner is correct.

“The whole premise behind an RLA is to provide the statistical confidence that the outcome is correct and it is based on the risk limit that has been set,” said Jennifer Morrell, an ex-election official in Utah and Colorado who now leads the Democracy Fund’s new Election Validation Project. “So the tighter the race, the more ballots will need to be retrieved and examined. I am sensitive to that, having run elections. I’m definitely sensitive to [the fact] that you might be asking, in a really tight race, an election administrator to have to audit more ballots than they would normally have to. What always comes up in states is how do we fit all of this in[to the workloads], the audit procedures? Because we always have to recount; we always have tight races.”

A handful of states will be conducting risk-limiting audits this fall. Some will be done before the winners are officially certified—like Colorado. Others are more akin to the pilot project in Virginia, an exploratory exercise. Compared to the vote verification a decade ago, they impose structure on a previously haphazard process. Proponents like Morrell, who oversaw RLAs in Colorado’s Arapahoe County, said they prompt everyone involved to be more meticulous about handling ballots. And she asserted their primary virtue, for public confidence, came from examining actual paper ballots.

“I see so many pluses that came out of having to pull the paper ballot. It forced me as an election official to really refine and think about and improve the way that we organized and tracked and stored and handled our ballots,” she said. “But having said that, let me just tell you, there’s something about going to the actual piece of paper marked by the voter. There is some level of confidence there.”

But in regional or statewide races, and especially those with photo finishes, the random ballot-pulling and statistical analysis can get complicated.

“That is part of the challenge,” said Patrick. “I think RLAs have a great purpose. But I also think that there has been a little bit of a bait and switch. Everyone has been told they are easy, they are simple, the math could be done: ‘Anyone can figure this math out. It’s not complicated.’ But in reality, the math is complicated, particularly when you are talking about a statewide race across multiple jurisdictions, and you also have to have the infrastructure in place to make sure you have your ballot manifests [inventorying and handling all the ballots], you have your cast vote record [the spreadsheet of every vote]. And all of these things have to be in place, so in fact you can go and pull the 73rd ballot from the 489th batch run on machine number two. If you don’t have that in place before, you’re not going to be able to do an RLA.”

Ballot Image Audits

This mix of ballot-handling concerns, methodological complexity and statistical math that many people do not understand leads to the hardest challenge facing those pushing RLAs—the fact that they are not easily explained. As Morrell said in a long interview, “Anyone who listens to all of this conversation would get lost. How much information does the public need to convince them that it was done correctly?”

That very question is not a trifle—not in our political era where truth, facts, objectivity and unpopular election results all are under attack, as evidenced by the president’s tweets. Not a day goes by without reports in newspapers like the New York Times about how social media is distorting political debates in harmful ways. Indeed, some of the most astute new political books are deconstructing and bemoaning this dark cultural trend.

As a professional culture, the world of elections—like the world of legislating and governing—often lags behind popular culture and technology. When it comes to vote counts, this also is true. In the past decade, there has been only one new voting machine maker accredited by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission. That firm is Clear Ballot, which relies on digital ballot images—capturing each side of every card that’s scanned while processing an individual’s overall ballot—to count and verify votes.

At roughly the same time that statisticians in academia were developing RLAs, the technologists who created Clear Ballot were focusing on how to build a voting system that could account for every ink mark on all the paper ballots cast. That is a different challenge than statistically verifying that the announced victor was correct—with 95 percent certainty. The firm developed products to read ballot ovals, grade how voters filled them in (confidently or not, based on the ink mark’s density), and to compile the results—and identify unreadable scans that needed further individual scrutiny.

Since 2016, Maryland has used Clear Ballot’s image-based software to audit its initial electronic scan of paper ballots—done by another manufacturer’s scanners.

On the Friday after 2018’s primary, the Maryland state Board of Elections (BOE) sent Clear Ballot CDs with images of 1.3 million ink-marked ovals and the giant spreadsheet with the most granular local results: the cast vote record. By Monday, it found about 1,100 ovals that didn’t correlate with initial scanner reading. By looking at those images more closely, it was able to resolve voter intent on most ballots, and tell the state BOE where to look for individual ballots—by precinct—if further investigation was warranted. (The state has rules where it would examine those ballots by hand in close contests.)

“We don’t think that technology can resolve an election,” said a top official with Clear Ballot who didn’t want to be named. “We believe the role of technology is to present the voter’s intent in such a way that unbiased human judges can decide on behalf of their constituents, and preserve that judgment indelibly… An election is a giant accounting problem, and we are trying to get a very precise apples-to-apples comparison.”

This executive said their process had a different goal than a statistical audit.

“We define an audit as not ‘did the right winner win,’ but as a comparison of two independently produced results that are derived from the same underlying data,” he said, adding that using digital images eliminated the Achilles’ heel of risk-limiting audits—the difficulties surrounding ballot custody, followed by the need to bring everyone into a single room to randomly pull ballots following rigorous math.

“Does the technology of ballot images change the way the country should look at auditing?” he asked. “Take RLAs out of the question. We can go to an all-digital world where human behavior does not play a role. Or play a role in such a way that you can go back and check it. What will be the effects on statutes, etc., when audits can be done routinely, well within the certification period [formally declaring winners]? I don’t mean sample audits. I mean complete, 100 percent, every contest, every ballot cast across every precinct. And do it before the certification window closes? And present the results on the internet, where the widest audience can look at it. Like we just did in Maryland.”

Indeed, in the state’s 2018 primary, there were four close contests where the state Board of Elections gave the candidates and campaigns access to Clear Ballot’s image-based inventory so they could look for themselves at the votes and decide whether to pursue recounts. The images were persuasive—and allowed the candidates in both sides to accept the result.

“We got a call from Nikki [Charlson, Maryland BOE deputy administrator]. She asked us to give them credentials. We did. We could see them pouring through the logs looking for votes. For us, it was a joy, to be able to provide that,” he said. “People could sit in their offices. Not have to assemble someplace. Be able to look across the entire population of ballots that had already been reconciled to the primary voting system’s results.”

Needless to say, if this high-tech scenario seems too good to be true—being able to verify millions of ink marks on paper before election winners are officially declared—it is not good enough for some supporters of risk-limiting audits, and for one particular reason: hacking fears. Simply put, while critics of risk-limiting audits say their biggest flaw is ballots are sloppily handled in real life (vanishing, reappearing), upending the math, critics of ballot image audits say hacking and falsifying digital images is also a real concern (and can be seen in online political missives this week).

No Perfect System

“Nobody is going to balk at the efficiency there,” Morrell said, of ballot images. “If I could get enough individuals that I talk to, to say that they would be comfortable with ballot images, and allowing the computer system—and these algorithms—to make those comparisons, I would be fine with it too, because it certainly would save a good deal of time. But having said that, let me just tell you, there’s something about actual paper.”

The EAC’s Lovato said he once frowned on paper’s inefficiencies, but he has changed his mind—and it’s not just a theoretical threat to him.

“One of the issues that arises, and one that you have probably heard from the computer scientists, is that you can’t trust the images,” he said. “I actually lean more toward that camp, just simply because there are voting system companies that do alter images. So, like the Dominion system, they produce what’s called an audit mark on their [scanned] ballot image—not on the actual ballot. So just by including that ballot mark, they are saying, ‘we manipulated the image.’ Whoever is viewing that can say that’s a good thing or a bad thing, but the bottom line is they are manipulating the image. So if they are able to do that, how can I as a concerned citizen say, ‘How do I know that they didn’t do something else to the image?’”

The EAC has not taken an official position on risk-limiting audits versus ballot image audits, although it has not funded pilot projects involving ballot images.

“I used to be in the camp that it’s not so likely,” Lovato said, referring to hacked voting systems. “I’m now in the camp that it’s more likely, at this point, when it comes to the cyber part of things. The other issue with Clear Ballot, as an audit usage, is the public perception side of the jurisdiction saying, ‘Okay, we spent hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars on this voting system that can produce images, and we’re going to rescan them on this other system?’ And what happens when the results differ between the two? Whose system do you trust at that point? How do you explain that to the public, to lawyers, to reporters? If I’m a local election official, I don’t want to get near that nightmare. But that is also a very real thing. I’ve seen that in the pilots that I have conducted with doing the different scanning—the difference in results.”

Clear Ballot executives counter that more data, and a more transparent process—where seeing is understanding, and understanding leads to believing—is the building block of more trustable elections. They also say the threat of hacking images is overblown.

“To do that requires an extraordinary amount of intelligence on the part of the scanner, in order to know where the ovals are, that one is to be moved elsewhere—it’s ridiculous,” one executive said. “How do you present the evidence to a partisan fan of a candidate that their candidate was not giving up, but really did lose by three votes? Until we came along, there was really no way to do that quickly.”

Why Not the Best of Both?

When voters start tuning in on election night to look for results, there will be some races that will be too close to call and will prompt election officials to take closer looks before announcing unofficial results—possibly taking days until the first results are released. (This is not the same as the media projecting winners.)

But between voters casting ballots and the official finish line, many people—to say nothing of candidates, campaign workers, political parties and press—will be looking for evidence trails that votes were counted correctly and double-checked to the greatest extent possible. In Maryland and a handful of counties across the country—including in Florida—ballot images will be used to verify vote totals before winners are declared. Other states, like Colorado, which votes by mail and at vote centers, will use risk-limiting audits. And yet others, like Michigan and Rhode Island, will pilot RLAs.

This landscape of new vote verification tools and techniques suggests that there is a probably a different, if not complementary and evolving, role for risk-limiting audits and for ballot image audits—depending on variables such as the closeness of initial counts; electorate size; how ballots are handled (at precincts or central counts); and the time and workload and budgetary constraints of the locales running elections.

“I think there has to be a sweet spot in the center where we can leverage all of the technologies as efficiently as possible and not go back to the draconian ways of doing things, because we just don’t have the time or resources to do that,” said Democracy Fund’s Patrick.

Whether the most confidence-inspiring technologies will be built into the ways America verifies the vote is no longer a theoretical question. The Brennan Center for Justice has noted that more than 30 states “say they must replace” their voting systems before the 2020 presidential election. At stake is public confidence for many years to come.

Also Available on: www.alternet.org