Presidential Primaries Strained by Civil Unrest and the Pandemic

(Post-2020 election protests at Arizona statehouse. Photo by Steven Rosenfeld)

The nine presidential primaries on June 2 occurred under crisis conditions not seen in America in 50 years—not since 1968, when protests, crackdowns and violence surrounded the presidential election—according to field reports from voting rights lawyers and advocacy groups.

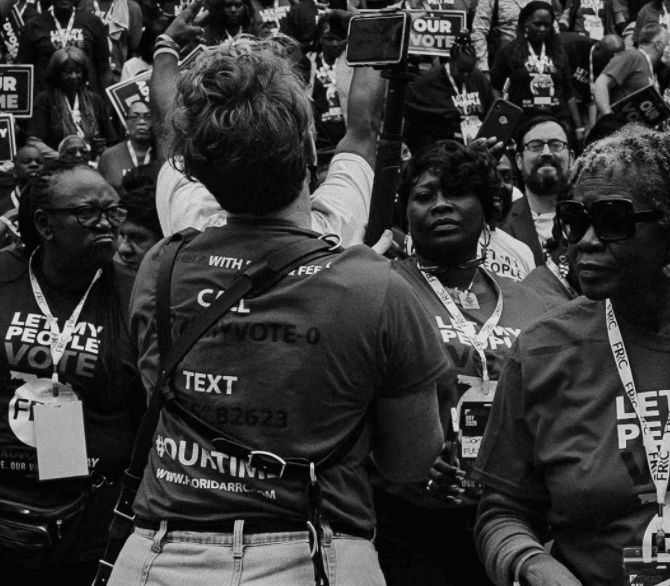

Non-white voters in Washington, D.C., Philadelphia and Pittsburgh said that they were intimidated but persevering to cast ballots inside municipal buildings that were also local police headquarters—some of them the same police departments that have been using excessive force to break up protests surrounding George Floyd’s death.

Responding to those reports, Erin Kramer, executive director of the nonprofit OnePA, which is based in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, said, “Many of us are persevering through state-sanctioned violence layered on top of a pandemic, which is a lot, and that is also true for voters.”

“Black voters are required to stand in line, while the police officers are entering and exiting the polling locations for official police business,” she said. “[This] is not exactly how people want to spend their Election Day. There are many examples.”

Kramer’s remarks were made in a briefing hosted by the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, a nonpartisan nonprofit that runs the largest nationwide Election Day hotline. Its midday briefing on presidential primaries in Pennsylvania, Washington, D.C., Indiana and New Mexico described an unfolding Election Day unlike any in recent memory. Typically, these briefings describe confusion faced by voters, unopened precincts and procedural barriers encountered by voters. But the nine primaries on June 2 are also taking place during a pandemic and amid civil unrest.

In Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, a swing county in a swing state, some poll workers were not using personal protective gear, the briefing noted, citing complaints from voters to the Lawyers’ Committee’s hotline. In New Mexico, where Native Americans are 11 percent of the electorate—but have 58 percent of the state’s COVID-19 cases—there are no in-person voting sites in Native American pueblos and on reservations, said Heather Ferguson, Common Cause New Mexico’s executive director.

“There are a number of curfews that are happening in New Mexico that have nothing to do with the current civil unrest,” she said. “There are no active voting sites on our Native American lands. And this is a huge problem… They are being systematically disenfranchised through this process. There are exceptions to that where they can leave their tribal nation lands and go through a checkpoint as long as they have a specific voting location… [It’s] another barrier that is preventing them from having easier access to exercise their right to vote.”

“We’ve seen the impact, in the last several days, of the curfew/curfews on voting,” said Marcia Johnson-Blanco, Lawyers’ Committee co-director. “This is indeed uncharted territory. For example, in D.C., today we have a curfew that begins at 7 [p.m.], but voting ends at 8 [p.m.]. And while voting has been deemed an essential practice, it’s unknown how that will be implemented in light of the curfew.”

These snapshots of difficulties facing voters were neither foreseen nor imagined before the pandemic struck in March and the death of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis set off national protests and law enforcement countermeasures. In Philadelphia, the mayor had to revise the hours of the curfew because it was slated to take effect before in-person voting closed at 8 p.m. (The curfew now takes effect at 8:30 p.m.)

These factors added to the confusion faced by many people who sought to vote by mail but did not receive an absentee ballot on time or sought to drop their ballot off in person so it would be counted.

“We are getting many questions about absentee ballots from voters who are not comfortable voting in person,” said Ami Gandhi, senior counsel for the Chicago Lawyers’ Committee chapter, which is monitoring voting in Indiana. “We want to remind everyone in Indiana that absentee ballots must be received by noon today, local time, by mail or hand delivery, in order to be counted. And if any voter is encountering a challenge, we encourage them to call us.”

As voting is governed mostly by state law and administered mostly by county officials, the experiences highlighted by the Lawyers’ Committee call were not happening everywhere there was an election on June 2—although these briefings do seek to identify trends affecting communities and large numbers of voters.

The report from Maryland, for example, where all active voters were mailed an absentee ballot, generally wasn’t problematic—apart from long lines to vote at several polls in Baltimore and the discovery that the wrong ballots had been mailed to two city districts. (Each district received the other district’s ballots.)

Later in the day, there were numerous reports from voters that they did not receive their requested mail-in ballot. However, because Maryland is among the states that offer same-day voter registration, that issue could be resolved.

However, stepping back, the June 2 primaries are anything but normal elections. Unfamiliarity with voting by mail (especially for, as OnePA’s Kramer said, voters who were not “whiter and wealthier”), consolidation of polling places in reaction to the pandemic, last-minute changes to when ballots have to be postmarked or delivered to count, and putting polls and ballot drop boxes in government buildings where voters have to mix with police are all new factors in play.

“We really are in uncharted territory for voting in America,” said Johnson-Blanco. “We won’t know the impact of the challenges we face today with voting until much later, and specifically, it’s going to be informative about how we vote in November.”

Also Available on: www.nationalmemo.com