Under Oath, Greene Insists She Was a ‘Victim’ of January 6 Riot

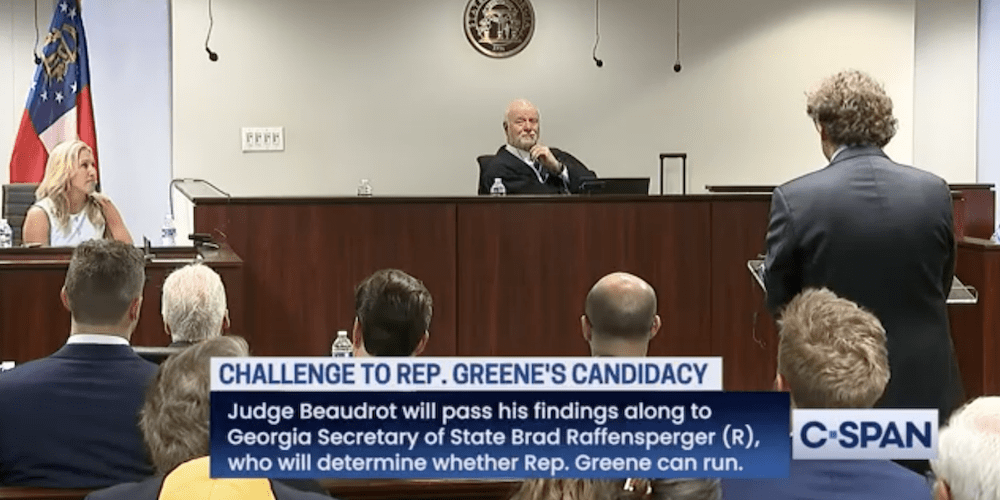

(Greene testifies in Georgia administrative law court. Photo via C-span.org)

Rep. Majorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) defended her right to remain on the 2022’s ballot in a Georgia courtroom on Friday by repeatedly saying that she could not recall, nor would take responsibility for, statements posted on social media or uttered on camera that encouraged the January 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol—where Greene insisted that she had been a victim of the violence.

“I was very scared. I was concerned. I was shocked, absolutely shocked,” Greene said. “Every time I [had] said, ‘We’re going to fight,’ it was all about objecting [to ratifying 2020’s Electoral College] and to me that was the most important process of the day. And I had no idea what was going on. And I just didn’t want anyone to get hurt… Yes, I was a victim of the riot that day.”

But Andrew Celli, Jr., the attorney representing a handful of Georgia voters who sued to remove Greene from the 2022 ballot under the U.S. Constitution’s 14th Amendment, which bars anyone from holding a federal or state office if they have “engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same,” urged Administrative Judge Charles Beaudrot to look past Greene’s denials to videos filmed a day before the insurrection — where she said that a peaceful transfer of power from Donald Trump to Joe Biden must be stopped by any means, including violence.

“You saw and heard it with your own eyes, judge. She said the quiet part out loud,” Celli said in his closing statement. “She spoke her truth out loud in a video that she made, that she posted on her own Facebook page, and that she wanted her hundreds of thousands of Facebook followers and the untold millions of other people that she wanted to know – that her point of view was you can’t allow… power to transfer peacefully.

“The is not Internet drivel. This is not the dark corners of Parler [a right-wing social media site]. This is a person who is a federal official, a member of government, and this wasn’t even a rhetorical flourish on the back of a campaign truck after a long day,” he said. “This is somebody who sat down in front of a camera and calmly and carefully told her viewers, ‘We will not accept a peaceful transfer of power. We can’t allow it.’ And then she said we will not go quietly into the night. She framed this as an existential battle, a new Fourth of July, a new Fourth of July 1776.”

Greene’s legal team, led by longtime Republican Party attorney James Bopp, Jr., replied that her statements were protected political speech. He cited Supreme Court rulings that distinguished between political speech that was overheated and speech that directly incited violent actions—which he said that Greene’s rhetoric had failed to do.

“[That’s] the reason there’s the protection of the First Amendment, which we have now seen on full display,” Bopp said. “Full display here—the danger of construing words way beyond their meaning to allow political opponents to smear their opposition in a court of law.”

Bopp said that the pro-Trump rally outside Congress on the morning of January 6, 2021, before the storming of the Capitol that ensued, was “peaceful and nonviolent.” He said that Greene’s support of the rally and her participation were constitutionally protected, whereas the riot and interruption of the joint session ratifying the Electoral College count were not constitutionally protected.

“And to drag her into, ‘Well, did you promote the rally?’ ‘Did you, you know, put it on your calendar?’ ‘Were you invited to speak?’ …is to strip her of her First Amendment rights,” Bopp said. “All of these are First Amendment protected activities, every single one of them. And none of them constitute even incitement, much less constitute engaging in unlawful conduct.”

Bopp contended that the constitutional questions raised by the lawsuit coordinated by Free Speech for People, a progressive law firm, to remove Greene from the 2022 ballot were not appropriate for the state tribunal. It will issue a recommendation to Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, who must decide whether Greene should remain on the May 24 primary ballot. Bopp also raised legal issues that Beaudrot could cite to recommend that Greene remain on the ballot, such as what activities legally constituted an insurrection, and noting that 2022’s primary ballots had already been printed and mailed out.

The administrative law judge appeared to be more interested in Bopp’s assertions than Celli’s arguments. Beaudrot told both sides to file final written arguments by next Thursday, April 28, and said he would issue a decision within a week after that.

But the hearing in the Office of State Administrative Hearings court was not designed to parse complex constitutional issues, as Beaudrot reminded the lawyers during the proceeding. It was, instead, a hearing to gather evidence about what Greene said and its impact.

Celli concluded that Greene’s rhetoric and actions supporting the January 6 insurrection disqualified her from seeking re-election to Congress. Bopp, of course, disagreed.

“We find ourselves back where we started—with the disqualification clause of the 14th Amendment and its three very simple requirements,” Celli said. “That the candidate for federal office had taken the oath to the Constitution; that an insurrection occurred; and that the candidate [in 2022, Greene] having taken that oath engaged in insurrection: promoted it, supported it, assisted it, [and] helped bring it into fruition.” “This is a political agenda,” Bopp said, “and this has been a political show trial.”