Voting Tech Gone Wrong: How Scrambled Data Upended a Nevada Caucus Site

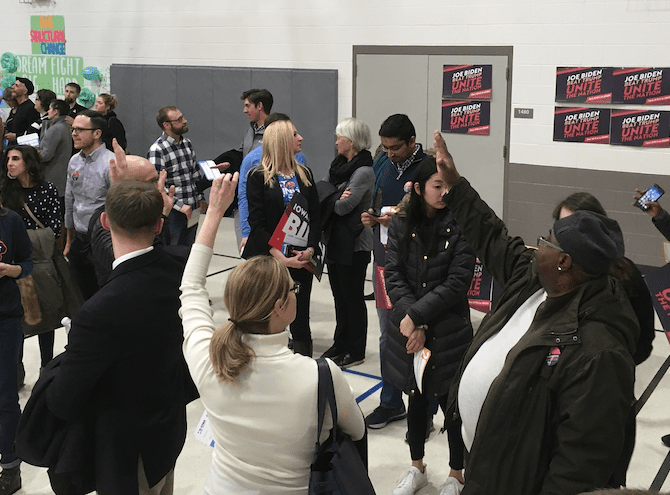

Three hours after Precinct 7632 began its Democratic presidential caucus in a corner of the basketball court at Bob Miller Middle School in Henderson, Nevada, the precinct chair reached the right person on the phone from the party’s operations center to resolve the vote-counting problem that bedeviled six precincts at the site—including hers.

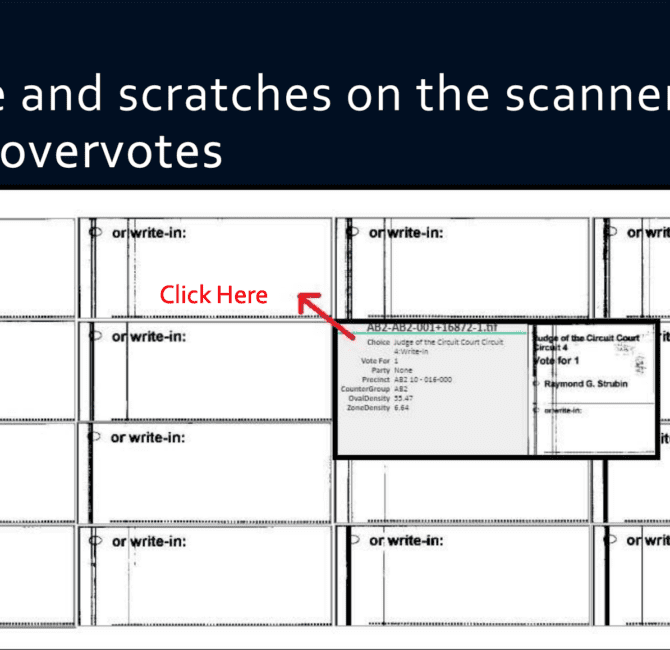

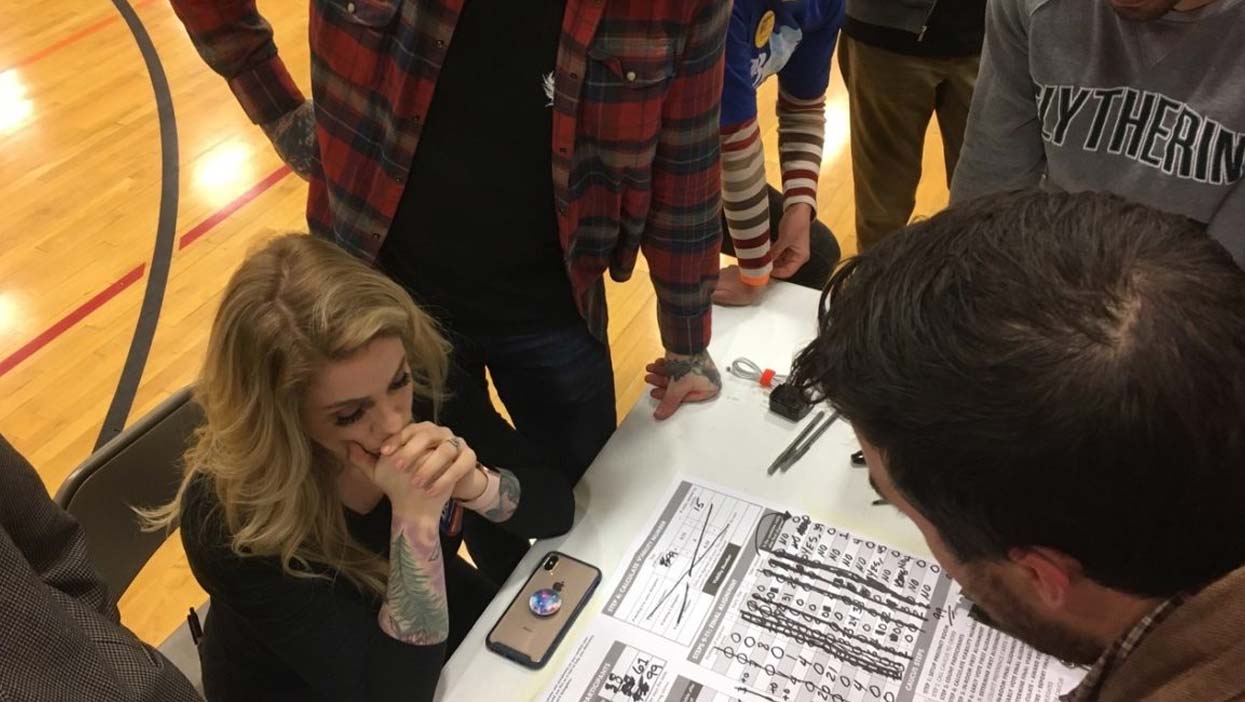

More than an hour before, the chair—Kathy, who didn’t want her last name used—slowly realized that incorrect numbers were appearing on an iPad that she had been given by the state party to her to run the caucus and determine its results. She had been following the Nevada State Democratic Party’s script and instructions. She directed the first round of in-person voting. She put its totals into a Google form on the iPad. Another volunteer serving as a precinct secretary wrote the numbers on a large worksheet for all to see.

The next step was integrating the precinct’s in-person votes with its early voting results, where participants ranked up to five choices for president. Kathy went to the next screen on her iPad and read aloud the early voting figures that were listed—those voters’ first choice. Then she used the iPad’s calculator to figure out which candidates had enough overall votes to see if they were entitled to county convention delegates. Those early votes surprisingly pushed Elizabeth Warren over the 15 percent viability threshold.

Then the first hints of trouble surfaced. As the second round of voting began among participants whose first choice wasn’t viable, Vinny Spotleson, the party’s site lead—or supervisor of the 13-precinct site—peered over Kathy’s shoulder to examine the iPad’s early-vote numbers. He was wondering if the results that she was reading aloud and the precinct secretary was entering on the worksheet belonged to another precinct.

“I’m going to keep going,” she said, as Spotleson stepped outside to make a phone call.”

It soon became clear that her iPad’s results were not her precinct’s early voters. The same scrambled data was affecting all four of the precincts in the school gym. Apparently, someone working at the party’s Las Vegas vote-counting hub, which was still processing the early votes until the night before the February 22 caucuses, made a data-entry error. The early vote totals were correct, but they had been sent to the wrong precinct.

“People were logging into apps that had the wrong precinct. We had the paper backups. Those all worked,” Spotleson later explained, referring to the remedy: using a printout of each precinct’s early votes to manually redo the realignment math that the state party planned to do electronically using the iPad’s “caucus calculator” and Google forms.

“There’s a total of six precincts that were basically shuffled within each other,” Spotleson continued. “From what I saw, they were having each other’s data from within the same [caucus] site. No one had a precinct’s data that wasn’t on my list… Hopefully, this is just my problem.”

Larger Patterns?

At about the same time that Precinct 7632’s chair had reached the operations center to double-check her math and results, the Associated Press declared that Sanders was the winner in a landslide—even though only 4 percent of precincts had reported. The AP’s declaration shifted the press’s focus away from whether Nevada would follow Iowa with a software-sparked results-reporting meltdown to Sanders’ status as the frontrunner.

But by early afternoon Sunday—more than 24 hours after the in-person caucus began and longer than it took the Iowa Democratic Party to release its 2020 caucus results—the Nevada state party had only released results from 60 percent of the precincts. While there were isolated reports of precinct chairs getting problematic early voting results on their iPads, the suggestion that there were wider problems came in a letter written after the Nevada caucuses closed from Pete Buttigieg’s senior staff to Nevada State Democratic Party (NSDP) Chair William McCurdy II.

“By most accounts, early voting itself was a success,” wrote Michael Gaffney, the Buttigieg campaign’s ballot access and delegate director, in the letter to the NSDP chair. “The process of integrating early votes into the results of the in-person precinct caucuses, however, was plagued with errors and inconsistencies. We received more than 200 incident reports from precincts around the state, including a few dozen related to how [the] early vote [was] factored into the in-person results.”

Gaffney’s letter described human and possible computer errors. He demanded the state party release all of its precinct results—noting that the party has been saying that its 2020 caucuses would be “the most accessible, expansive, and transparent.” (Early on Sunday, the party’s spokeswoman rejected his request to release the precinct data.)

The process and technology used in Nevada’s caucuses were not the same as Iowa’s. Nevada’s party-run process was more complex due to offering an early voting option using a ranked-choice ballot. After Iowa had to manually tally its results after the failure of its reporting software—which Nevada also planned to use—the Nevada party quickly put together a substitute system.

Nevada would use party-owned iPads and Google forms to integrate the results from four days of early voting with in-person voting at nearly 2,000 precincts. There also would be a paper record trail of all of the voting. But the Nevada party believed, just like the Iowa party, that the paper backups would not be needed. That assumption, shared widely by senior party officials who mostly grew up in the internet era, was wrong.

As six of the Henderson middle school’s 13 precincts discovered, the high-tech system had problems, and it took some doing to figure out what went wrong and how to fix it—all while caucus participants waited and watched.

“I’m not using the iPad anymore, because it’s screwed up,” said Josh Reid, the chair at Precinct 7633—in another corner of the gym. “We’re using regular [paper] methods.”

Ironies and Frustrations

While precinct chairs struggled to sort out the numbers, caucus participants who were milling around the basketball court noted the irony that digital technology that was intended to streamline the process was instead adding new errors and complexity to an already tedious process—in a campaign cycle filled with cyber-based threats.

“The whole concern about technology and where it can fail, and where the compromises are, and the Russians, and everything else—there would be none of that if we did what they are resorting to now—using paper,” said Richard Biegel, who is CEO of a startup focusing on parenting and childhood-development research. “They just set the iPad aside and started using the paper. The irony is what worked is paper. It still works.”

In Biegel’s precinct in another corner of the gym, some voters went from seeing their presidential pick win county delegates to winning no delegates—as they did not meet the viability threshold once the correct early vote results were added in.

“Initially, what we believed from the first round of voting was that four candidates were viable,” he said. “Then they discovered that there was a problem. They were supposed to have seven delegates. By their math [via the iPad’s data and tools] they had eight. It was like, ‘Okay. There’s a problem.’ When they went to check the paper [backup of early votes], they realized, ‘Yes, it wasn’t a little problem. We were given the wrong numbers.’ When they recalculated the numbers, there were only two candidates that were viable.”

While the process was intricate enough, these twists and turns were also frustrating.

“The data scrambling that we are witnessing here had us lose three Bernie votes in my section [precinct] and eight Bernie votes in that section [another precinct],” said Vasil Cvetkovski, a PhD political science student at University of Nevada, Las Vegas. “So after we recounted it, we found out that Bernie should have been viable in one of the sections. The only reason we were able to catch that was because we have paper ballot trails.”

Cvetkovski was also not impressed by caucus math that rounded results up and down to award delegates, but sometimes undermined the precinct’s popular vote winners.

“As a political scientist, this is the last way that I would arrange the caucus to elect a democratic nominee,” he said. “I find it suspect. One group can have about 25 extra people than is needed to make the candidate valid, while another group can be one vote short and we can’t send one person from our group to that group over there.”

Others said the complexity and technical snafus undermined their confidence in the results.

“All this confusion and ridiculousness of not understanding the math and how this is going—with trying to combine early voting and caucusing. I feel like all of us and everybody here is frustrated,” said Angel Rasmussen, who is about to start graduate school at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. “I feel like it should definitely be a primary from here on out—in Iowa, here, pretty much everywhere, so we don’t have to deal with all this nonsense.”

No More Caucuses?

On Sunday, Nevada’s most influential Democrat—former U.S. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, who used his influence to push the Democratic National Committee to make Nevada’s caucuses the first presidential nominating contest in a Western state—said it was time to switch from a party-run caucus to a government-run primary in 2024.

Reid issued a statement that praised “the Nevada Democratic Party, its talented staff, and the thousands of grassroots volunteers who have done so much hard work over the years to build this operation.” But he used more blunt language with the New York Times, telling its reporter, “All caucuses should be a thing of the past. They don’t work for a multitude of reasons.”

But if the Nevada State Democratic Party’s 2020 caucus is to be its last—which remains to be seen—it should be noted that some of the country’s most technically adept experts and committed Democratic Party officials converged on Nevada to retool a caucus voting system in less than three weeks after the results-reporting software failed in Iowa.

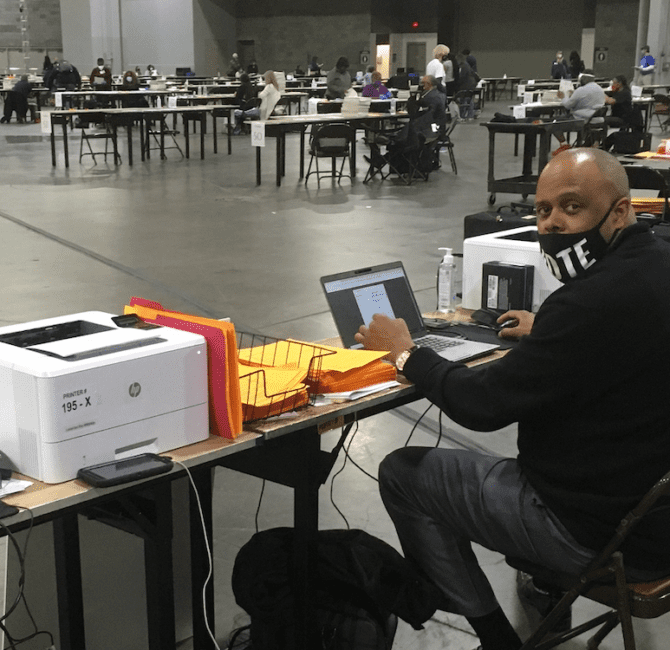

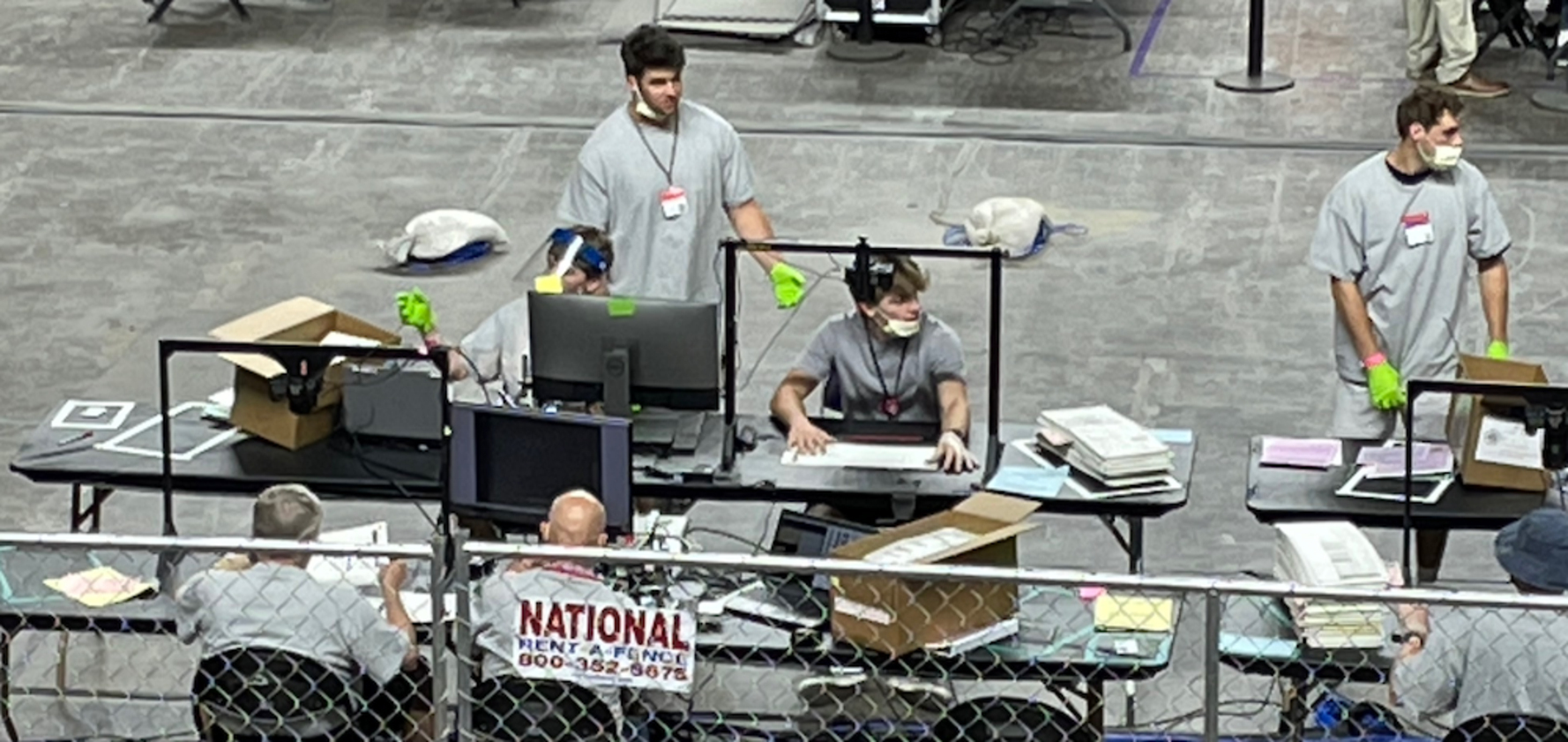

After Iowa, the DNC and state parties across the country sent in every available person. More than 2,500 people who would be precinct chairs and caucus site leads went through multiple trainings in recent weeks—even as the process was being revised. Google sent in staff to ensure its data tools would work to register voters, record ranked choice-ballots, integrate those results with Google forms and calculators on iPads, and to compile the statewide totals. DigiDems, a San Francisco-based incubator for Democratic political campaigns, also sent people.

Yet all of that technology and brainpower that put together a sophisticated voting system didn’t anticipate the human errors that marred the process. Some of the people manning the system—no doubt overtired and pressing ahead—made the data-entry mistakes handling blocks of data that went through the system the following day. When the early voting data resurfaced in precinct caucuses in Henderson and elsewhere, it led to breakdowns.

“The data [taken from scanners counting the early voting ballots] was input late last night in various places,” said a DNC member volunteering for one candidate. “I think the problem here was not the technology. It was the data entry… People who I know were sitting at desktops and manually entering the data.”

Also Available on: www.alternet.org