Why the 2020 Iowa Democratic Caucuses Could Become a Definitive Showcase for Online Voting

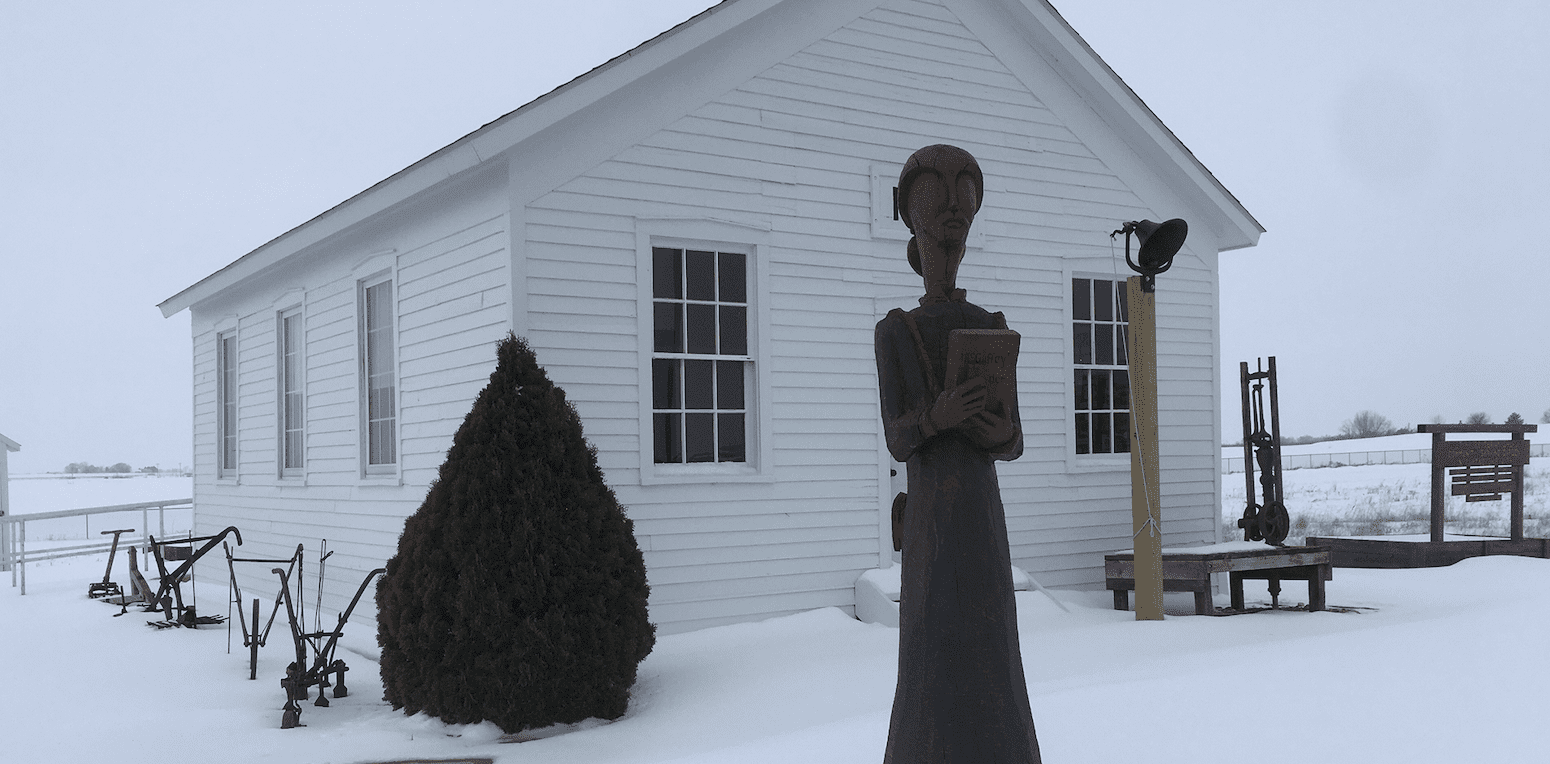

(Photo / Steven Rosenfeld)

If all goes according to plans now being drafted, Iowa’s 2020 Democratic presidential caucuses may be the biggest demonstration of — and test for — online voting in a single U.S. election in years.

But before participating in Iowa’s caucuses online from home or a coffee shop becomes a reality on February 3, 2020, its state Democratic Party must deploy a formidable voting infrastructure and a legion of trained operators to avoid a mix of human errors and technical issues that have marred online participation in recent Republican presidential and statewide caucuses.

The most eyebrow-raising examples of unanticipated snafus come from Utah, notably in 2016’s GOP presidential caucuses and 2018’s GOP party caucuses. Both years, simple but stubborn obstacles surfaced and impeded voting via different online systems.

In 2016, the Utah Republican party opted to caucus instead of holding a primary election, a departure from 2012 when state and county election offices oversaw that vote. The GOP envisioned a hybrid process: most party members caucusing in person but a sizable number taking part online. It enlisted one of the world’s best-respected election contractors to stage and run the voting mechanics. But the party’s insistence on using an event-planning app for caucus registration floundered — literally blocking access at the front door before any voting could take place.

One Utah state election official who watched from the sidelines said thousands of people were unable to register online or get through to telephone help lines to the party or vendor. As a result, Utah’s government election offices received more phone calls that evening than in any prior election — but couldn’t offer help because they weren’t running the caucuses. He estimated that “one-quarter of the people weren’t, ultimately, able to vote online.”

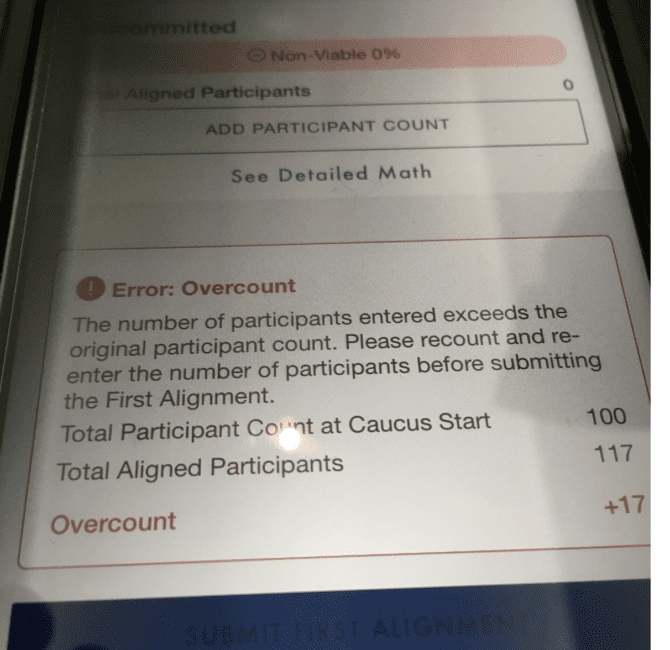

Two years later in state-level caucuses, Utah’s GOP chose a different vendor so people could vote from smartphones at caucus sites. However, waves of party members arrived not having downloaded the app and soon flooded app stores, Wired.com noted, blocking large numbers from getting the app. Some party members thought their in-house election was the victim of a denial of service attack. That wasn’t the only snafu, however, as those who successfully downloaded the app still had to get through an authentication process as the clock ran out. Those obstacles left thousands of participants reverting to paper ballots, Apple Store reviews said.

These incidents underscore the challenges faced by Iowa’s Democratic Party to bring online participation to the 2020 caucus. While there are always difficulties in deploying new systems, company technologists and executives who have successfully deployed online voting — mostly overseas — didn’t say that the Iowa party could not rise to the challenge. But almost all said that the time for planning and preparation was tight, and many factors — technological and human — had to be properly anticipated and countered under the best of circumstances. Several said they saw no upside in their firms bidding for an Iowa contract.

Nonetheless, the party is now finishing its draft of plans allowing registered Democrats who are not present to participate, said Kevin Geiken, the party’s executive director. He estimated that 100,000 registered Democratic Iowans could participate online in 2020. That would be in addition to the number of people who physically attend the party’s 1,679 caucuses — 171,500 Iowans took part in 2016.

Geiken’s estimate would place the online turnout on par with all military service members nationwide who used online platforms to vote in 2016. (Half the states offered this option, usually in smaller pilot projects.)

“That’s where we are right now — looking at the people or companies or vendors that have the technological background and capacity to fit something to our very unique needs, and a willingness to do that,” Geiken said. “Once we get the DSP — delegate selection plan — through the [Iowa state party’s] Central Committee, we’ll start an aggressive RFP [Request for Proposals] process.”

Iowa, like a handful of other states where Democrats will hold a presidential caucus and not a primary, is responding to new 2020 Delegate Selection Rules from the Democratic National Committee. The DNC hopes to open up the process with online participation and same-day registration. It also requires a capacity to audit and recount votes.

Where the DNC has set policy goals, it has left states to work out the details. The puzzle that the Iowa party must solve is standing up a system where off-site votes will stream into 1,679 caucus sites and be coordinated with counts of people assembled in precincts for successive rounds of voting (as less popular candidates are disqualified).

In a perfect world, this is a lot of moving parts that must mesh like clockwork. But elections in general — and citizen-run caucuses especially — don’t exist in perfect worlds. They have many human and technical dimensions, where things can go wrong despite the best intentions and plans. Indeed, one can look no further than the last two presidential cycles in Iowa, where, in both parties, there was no clear winner. (This was using decades-old voting practices — not new online voting.)

In 2012, the Iowa Republican Party did not get the complete results on caucus night and incorrectly named Mitt Romney as the winner. The more establishment Republican took the headlines and momentum heading into New Hampshire, not Rick Santorum who was later found to have won 34 more votes (out of 59,644 for the pair) and despite eight precincts where no votes had been counted.

In 2016, a similar dynamic struck Iowa’s Democratic caucuses. In a night with poor administration at more than a few sites (Iowa’s largest paper editorialized, “Once again the world is laughing”), Hillary Clinton emerged with 700.47 delegate equivalents to the process’s next stage, compared to 696.92 for Bernie Sanders. Iowa’s pro-establishment Democratic leadership released no raw vote totals. The 2020 DNC rules, in response, demand a transparent and auditable caucus process.

Executives at companies that have run online elections in Canada and the Philippines said the nuts and bolts were technically achievable — from candidate-ranking ballots that could be automatically counted for the rounds of voting, to coordinating action at nearly 1,700 caucus sites with party headquarters. They even said online voting, with encryption and unique identifiers, offered a tighter recount and audit trail than mail-in paper ballots (a contention that many domestic election integrity activists would disagree with). But those virtues still can fall victim to human errors, from unfamiliarity with new voting systems to lapses in technical and administrative preparation, according to interviews with election officials, former state party chairs and voting technology company executives.

“A lot of these problems are there is no familiarity — that it’s new,” said Robert Graham, the Arizona Republican Party’s former chairman, who successfully used online voting for his party’s 2016 presidential delegate selection at a state convention attended by 1,200 party members. “But the second part of it is the logistical, operations flow. If they don’t think this through properly, you get headaches. And people get violently upset when you start screwing with their elections. That’s a big, big risk for anyone considering this.”

If you want examples where best-laid plans were ruined by unanticipated snafus, look no further than the Utah GOP and its recent online voting experience.

The Republican experience online

In 2016, the Utah Republican Party decided to do what Iowa Democrats are considering: change aspects of the voting process whereby party members choose their presidential nominee. The Utah GOP scrapped statewide primaries and opted to caucus instead, including offering an online participation option to a bloc of voters who signed up beforehand. Because the GOP caucus was a privately run affair, there are conflicting accounts of what ensued.

The state’s media reported that voter interest and turnout was extremely high at both major party’s caucus sites — “unprecedented,” as Deseret News said. The newspaper also said 59,000 GOP voters signed up “to cast their ballots via computers, smartphones or tablets in one [of] the first prominent uses of online voting in the U.S.” This is where some details get squishy. The Utah GOP — which would not comment for this report — had a cap on the number of online participants, according to a high-ranking state election official who was also a Republican.

The state party hired one of the best-respected international voting technology forms, Smartmatic, to handle the balloting. The state official — whose agency didn’t run the caucus—recalled that, “something like 40,000 people signed up,” or expected to caucus online. Smartmatic’s case study report said there were 27,490 participants, of which 90 percent successfully took part. It didn’t explain what happened to the rest.

What’s clear, however, was thousands of Republicans tried but failed to access the online platform. The state official said he heard that there were “around 10,000 people who weren’t ultimately able to get in.” Utah’s state and county offices received more phone calls seeking help that night than in any prior election, he said. They didn’t realize they were calling an agency that had nothing to do with the process. So what happened?

It turns out that Utah’s GOP used a mix of vendors for different aspects of its operation. Smartmatic oversaw the voting — which included giving every voter a 30-digit pass code to log in. (That was challenging for some voters.) But apparently the party, following the Republican National Committee’s directions, used Eventbrite, an online event-planning app for registration. The app was unable to handle demands at traffic peaks — including by some voters who were not registered Republicans but wanted to join the presidential caucus. (Official voter registration records have different data and security than what’s typically sought on online event apps.)

“The issue was their registration system, not their voting system,” said Richard Ades, Smartmatic’s Washington-based spokesman. “Against better advice, they [Utah’s GOP] used Eventbrite to register people. So all of the problems they were having on Election Day were because they weren’t registered or wanted to register that day.”

In other words, there was a confluence of unforeseen factors: voters making a dash to use a possibly unfamiliar online application; that app not anticipating vagaries like non-party members wanting to participate; and traffic creating a log-in bottleneck that excluded a large number of participants. Why might the party have used an event app instead of a more formal registration tool? Again, no one from the Utah party would comment. But in a 2016 interview about Utah’s online voting, Joseph Mohen, the technologist whose start-up spent $7.5 million to develop an online voting system for the Arizona Democratic caucus in 2000, said he heard that Utah’s GOP spent $180,000 for its event. His contrast implied cost may have been a factor.

Utah Republicans’ rough experience with online voting doesn’t end there. In spring 2018, a similar snafu unexpectedly happened with a different vendor as the party was trying to use smartphone-based voting for local and state caucuses. Many party members did not download the app until they were at caucus sites, Wired.com reported, creating a delay at iPhone and Android stores. Some frustrated voters thought this technical logjam was an insidious hacking attack, according to one industry consultant.

“Our county tried to use this system for a party convention yesterday,” an Apple Store review said. “We had about 1,400 people trying to use this thing. It did not work. The back end failed utterly and finally it was abandoned. We used paper ballots instead. By the way it also failed during many local caucus meetings a few weeks before. Out of 273 caucus meetings it only worked for three of them.”

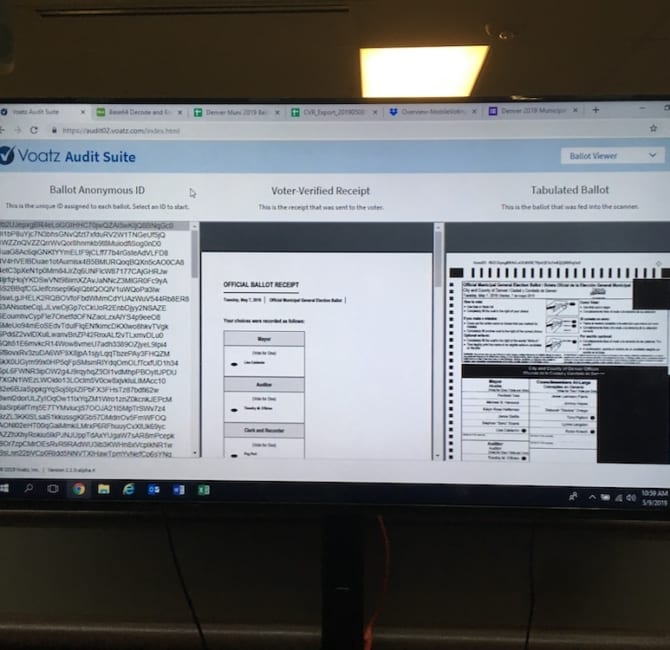

(This same app, from Voatz.com, was used successfully this past November for West Virginia’s overseas military voters — a process involving 144 voters in 24 countries.)

The art of the possible

There are different ways one can view these online caucus precedents. One can blame vendors and the technology. One can blame party officials for mandating voting systems that they don’t understand that end up undermining public confidence. On the other hand, one can more astutely contend that if these cutting-edge firms working with state parties could not make online voting work on a big scale, then nobody can; at least, not yet.

Notably, Utah’s woes are not indicative of all the recent online voting experiences. In Arizona, the state GOP has been using a Canadian-based system, from a vendor called Simply Voting, to conduct its presidential delegate selection and also its local party elections, said Robert Graham, the former Arizona state party chair.

“It was the most efficient party election I have ever been in,” Graham said, speaking of 2016’s process before the Republican National Convention.

The Arizona party held that caucus in one location, where 1,200 known participants first had to sign in before getting an envelope with a unique identifier and URL to get their ballot and vote online. (Importantly, that process did not use an app, but website-based ballot screens—which Smartmatic provided to Utah’s GOP until the party’s registration app blocked access.) Arizona caucus participants then used their smartphones, tablets or kiosks in the convention center to vote. As in Iowa’s Democratic caucuses, some contests had successive rounds of voting. The online ballot was reset as the field of candidates narrowed.

Graham said the key to a successful online voting event was a great deal of planning, training, testing, mock elections and redundant communication — all to anticipate and ward off what can go wrong. All that is doubtless true, no matter what scale of an online election is held. But it would be erroneous to suggest that having online voting in one locale with 1,200 known participants could be readily transported to Iowa’s 1,679 precincts with possibly hundreds of thousands of participants, including physical caucus sites offering same-day party registration to eligible voters.

Graham spoke about how the 2016 presidential caucus was a successful online election (even with protests from Trump supporters who didn’t get as many votes as they expected) for key reasons. His event was in one location. It had a finite number of participants. It had a relatively straightforward tabulation and counting process. The campaigns had signed off on the system before it was used. Graham even enlisted teams of tech-savvy young people to politely peer over people’s shoulders while getting online—to offer assistance, just in case something confusing popped up.

The complexity of what Iowa Democrats must set up in 2020 is of a different magnitude. It involves creating an online technical architecture that can handle simultaneous voting in upward of 1,700 precincts — when early caucus sites are added. Remote ballots will come from a mix of online digital and landline telephone interfaces. Off-site voting data and tabulations will have to be received by someone manning the system at each caucus site—and monitored statewide. The off-site totals will have to be coordinated with tallies in the room. And this will have to be done repeatedly, in each location, until the results are final—including possibly having recounts when there are ties and challenges from thwarted candidates.

Every voting company executive interviewed said getting these elements right—the customized hardware, software, testing, training, deployment, mock elections, customer service and more — was formidable. More than one executive said their company would not likely bid on it — as they didn’t see many upsides. One said the caucuses were more like managing an event, not an election. Another said there were too many unpredictable variables, when voting systems are designed to be predictable. Only one — Smartmatic — was not entirely daunted, saying it had recently managed its third national election in the Philippines from start to finish in about nine months. What Iowa Democrats seek to do is not impossible, the company’s technologists said in background briefings, but it was very challenging.

What can go wrong?

Based on interviews with many party officials, vendors and government election officials, the lingering impression was there might be more difficulties with the human dimensions of getting online voting right than the technical dimensions of managing vote-count data streams.

For instance, Bret Scofield, Simply Voting’s vice president, said tabulation technology exists to handle the various streams of data for each round of Iowa-style caucus voting. He said there were 200 municipalities in the Canadian province of Ontario that conduct local elections using online devices and landline phones. “If you plan for those streams well enough, then everything can be unified into a single result at the end,” he said.

Smartmatic’s experts concurred, saying that the off-site ballots could be designed in such a way as to rank a voter’s preference of candidates — but granted some flexibility for a realignment depending on what unfolded at caucus sites — and still automate all of the off-site vote counting. They also said that encryption advances allowed for rapid transparent audits and traceable recounts — more so than handling paper ballots. While that contention may be true, many domestic election policy experts, election integrity activists and party volunteers currently distrust almost anything electronic in voting.

These crosscurrents raise a larger point. Scofield said it often takes several years of planning, development and testing before successfully deploying new online voting systems — including winning public confidence. For example, for Canadian elections, Simply Voting has often had to work with a government-selected auditor throughout this entire process — for public assurance that the technology was accurate and the experience was designed to be voter-friendly.

But Scofield also said that technical complications were also real. In last fall’s Ontario municipal elections, one of his competitors “got throttled” by telecom firms that wouldn’t provide the bandwidth it had assumed would be there for the voting data stream under peak demand on Election Day. “You can look it up in the news. Something like 50 municipalities had to extend their election a day,” he said.

This is the territory that the DNC is heading into by asking high-profile 2020 caucus states like Iowa and Nevada to plan for online participation. In Canada, Scofield’s boss raised eyebrows when he said in 2016 that Canada’s federal elections should not yet be conducted online — because of the stakes, public unfamiliarity with the system, and the cybersecurity protections needed. “It’s one thing to protect against people who are disgruntled versus state actors that may have resources above and beyond what a private company might have,” he said.

Currently, the Iowa Democratic Party is on track to issue a draft plan for 2020’s caucuses by mid-February. The DNC Rules Committee will review those plans later in the spring, deciding then to approve or reject them. Elaine Kamarck, a longtime Rules Committee member who also is a historian specializing in presidential nominating contests, said there was little margin for error given the Iowa contest’s stakes.

“Given the outsized importance of Iowa on the New Hampshire primary — because that is really what it does; it defines who is going into New Hampshire with some momentum — the Iowa system has to be bug-free,” Kamarck said. “Other than that, the only thing I can really say is the Rules Committee will look at the Iowa delegate selection plan and try to ascertain whether this is a plan they have the capacity to implement, and whether or not we think this is going to work.”

Most Democratic Party officials interviewed were not aware of the experience of state Republican Parties using online voting for their recent caucuses. But they are poised to take a much harder look, now that they must translate DNC policy into reality.

“We are going to look for state party capacity when it comes to the caucus’ delegate selection plan,” Kamarck said. “How likely is it that the state parties will be able to perform, [to] do what they say they are going to do? That’s the first thing we will do. We will also look for some way to make sure that the system is transparent enough, so if you have a close race that people know with some certainty what the results were. That’s all I can say about this right now.”

Also Available on: www.salon.com