Why Younger Voters Are More Likely to Have Their Absentee Ballots Rejected

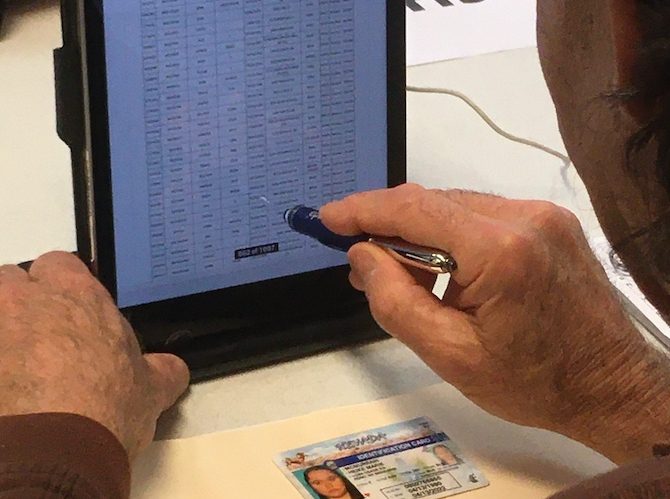

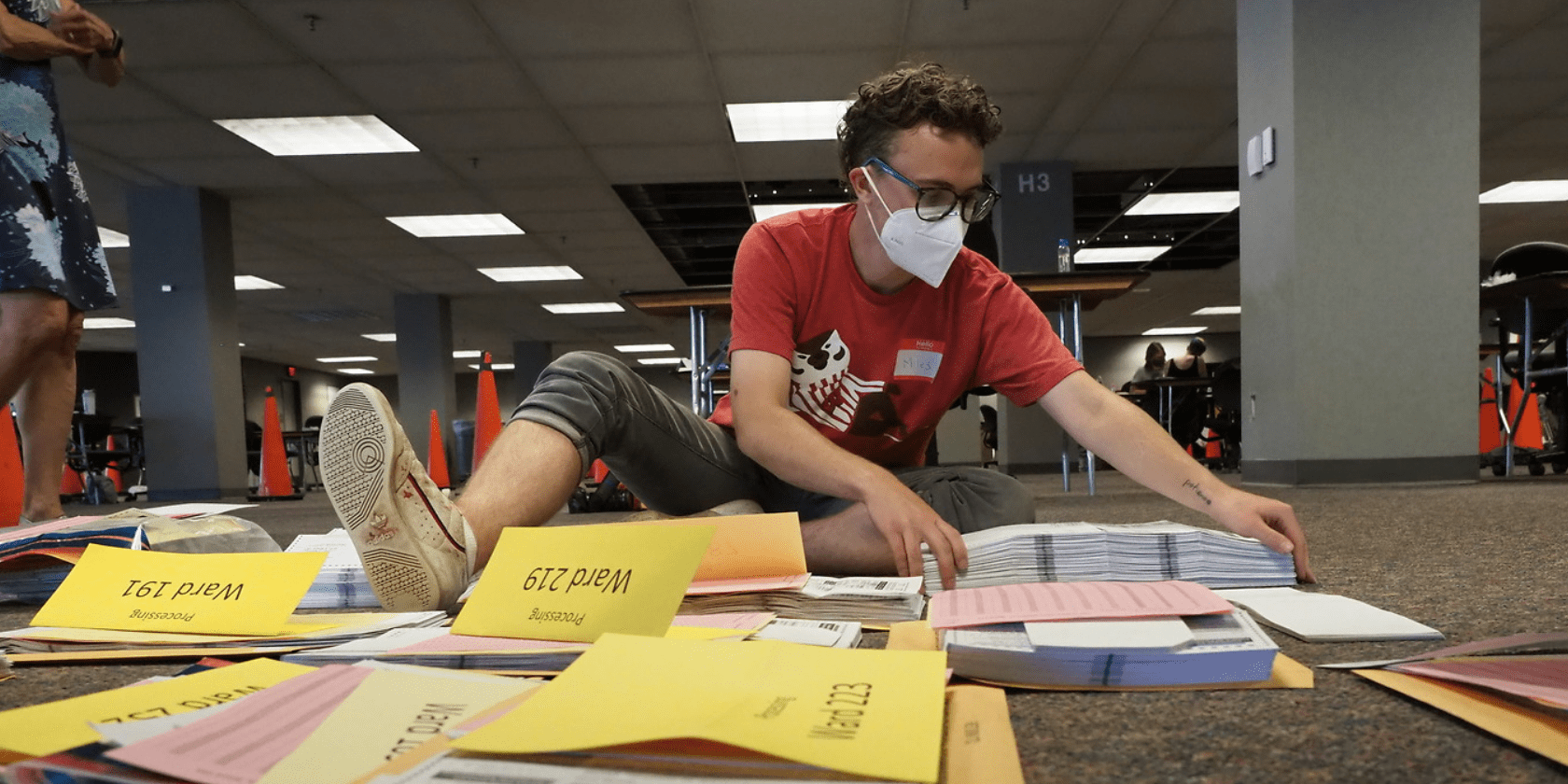

(Photo by Sue Dorfman / Zuma Press)

As half or more of the 2020 presidential election’s votes will be cast on mailed-out ballots, a new study on why absentee ballots were rejected in three urban California counties in 2018 reveals why young voters’ ballots were rejected at triple the rate of all voters.

Nationally, it is well known that absentee ballots arriving after state deadlines, problems with a voter’s signature on the return envelope not matching their voter registration form, or a missing signature account for more than half of all rejected ballots, as the latest federal statistics affirm. But a new California Voter Foundation (CVF) study reveals the most likely causes behind those errors, especially for young voters.

In short, the study notes that young (ages 18-34) voters’ signatures can change between registering to vote and voting, causing mismatches on return envelopes. (The envelopes don’t remind voters that their signature has to match their voter registration.)

Additionally, young voters often wait until the last minute to vote, not realizing that voting with an absentee ballot has more steps than voting at an in-person polling place. And young voters may be unfamiliar with mail delivery timetables, leading ballots to arrive past return deadlines.

“In Sacramento County, young voters age 18-24 were most likely to have their ballot rejected due to a mismatched signature, followed by lateness. Voters age 25-34 also had a high rate of non-matching signatures,” the study said. “These factors may be due to young voters’ likely lack of familiarity with using the U.S. Postal Service as well as the possibility that their signature was not fully formed at the time they registered to vote.”

On the other end of the voter age range, a different human factor related to aging—being forgetful—was a cause behind absentee ballot rejections for older voters, the study also found, atop missing filing deadlines.

“Older voters, age 55-64 and age 65 and over are more likely to neglect to sign their ballot envelope than voters in other age groups and to have their ballots rejected for this reason,” the CVF report said.

The study looked at the absentee ballot-rejection rates in the November 2018 election in the counties of Sacramento, San Mateo and Santa Clara. The rejection rates for voters age 18-24 in those counties were 2.3 percent, 3.5 percent and 2.5 percent, respectively, compared to 0.8 percent, 1.0 percent and 0.7 percent for all voters. The rejection rates for voters age 25-34 were nearly double that of all voters.

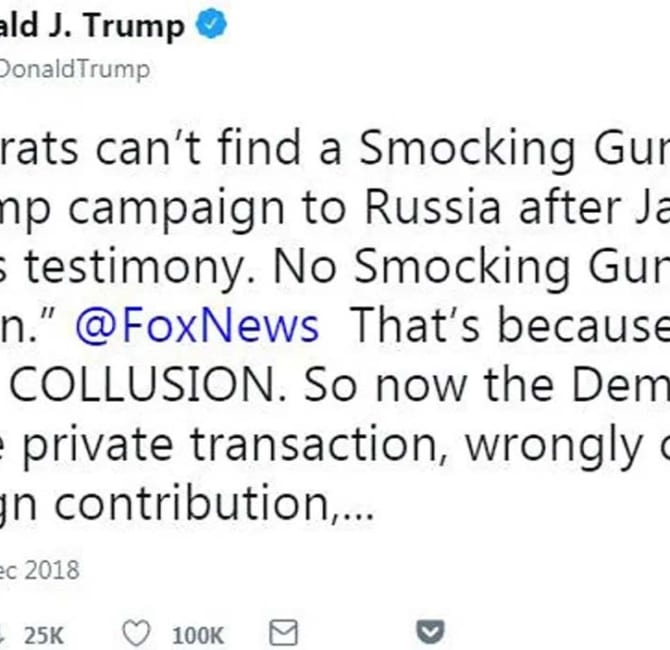

While much attention continues to be foisted on how the Trump administration is trying to subvert postal delivery of ballots and undermine public confidence in voting with mailed-out ballots in the 2020 fall election, the CVF study was a reminder that human factors are part of the equation of whether one’s vote will be counted.

“Casting a vote-by-mail ballot is an important safety measure to ensure people can vote during the coronavirus pandemic without putting their or other[s’] health at risk,” said Kim Alexander, CVF’s president and co-author of the report, “Improving California’s Vote-by-Mail Process by Reducing Ballot Rejection: A Three-County Study.”

“But it shifts responsibility for getting it right from poll workers to voters,” she continued. “Late return and envelope signatures missing or not sufficiently matching voters’ signatures on file are the leading reasons why some ballots are rejected.”

A Looking Glass into National Trends

The CVF report illuminates causes behind what could become one of the most contentious vote-counting issues in swing states if the election is close and early results are challenged: the discovery of higher ballot-rejection rates among some populations but not others.

The pandemic’s rapid shift to voting with mailed-out ballots is one of the biggest changes in American democracy in years. While a small percentage of returned ballots have always been rejected, the rapid expansion of voting by mail in 2020’s primaries led to higher rejection rates, according to early analyses. Nationally, the rejection rate was 1.4 percent in the 2017-2018 cycle. But so far in 2020, the rate has been 2 percent or higher in a few swing states.

As of September 16, 59 million ballots were on track to be mailed to voters for the general election. As of that date, four states—North Carolina, South Carolina, Illinois and Florida—have seen about 59,000 voters return their presidential election ballots, according to University of Florida political scientist Michael McDonald. Almost all of those returned ballots were in North Carolina, the first state to mail out ballots. The first 10,000 ballots had a rejection rate of about 2 percent, CNN reported, noting that the rate for Black voters was “nearly 7 percent.”

Nationally, there is ongoing litigation led by Democratic Party lawyers to push states to change their ballot envelope review procedures to try to lower signature-based rejection rates. Many of these lawsuits were filed months ago and are just now being resolved. In Pennsylvania on September 14, a federal suit was withdrawn after statewide election officials issued “new guidance” that signature mismatches could not be the sole reason to reject a voter’s absentee ballot.

These lawsuits’ focus is the part of the process that involves reviewing and checking in a ballot return envelope at election offices—much like a voter is checked into their precinct by the poll worker. The signature and other information on the ballot return envelope are compared to a signature on file and other identifying information in voter records. These lawsuits seek better matching standards and a way for voters to “cure” any problem that surfaces.

Over the past decade, California’s ballot-rejection rates have been on par with national trends, with 1.7 percent of California’s vote-by-mail ballots being rejected, the CVF study said. It also illuminated some of the reasons why ballots were being rejected—and why different age groups were prone to variations in error rates and types.

“[T]he top three reasons… are that voters returned them too late to count, they neglected to sign the ballot envelope, or the signature they provided on the envelope did not sufficiently match their voter registration signature on file with the county,” the study said, summarizing.

But there were other reasons for rejected ballots, it found. Some return envelopes were empty. Some envelopes were from past elections. Some people voted in person after mailing in their ballot. Some voters had died, but a family member returned their ballot. Sometimes more than one ballot was put in a single envelope. Some voters mixed up their household’s ballots, and used another voter’s return envelope for their ballot.

The CVF study also noted that human factors in election administration made a difference in giving voters a chance to fix one of the top causes of rejections: signature mismatches.

One example came from Sacramento County. In the November 2018 election, 39.6 percent of the county’s rejected ballots were due to non-matching signatures, compared to 4.4 percent in San Mateo County and 9.5 percent in Santa Clara County, the study found. (The national rate for non-matching was 15.8 percent in 2017-18, according to federal statistics.) Sacramento County’s discrepancy was due to an administrative decision to not double-check the return envelope signature that had been questioned, CVF said.

“The likely reason for this relatively higher rate of rejection for non-matching signatures in Sacramento’s November 2018 election was a change in the office’s leadership that took place immediately after Election Day, and a procedure that had been in place in prior elections, requiring a second review by election staff or an election supervisor of challenged signatures, was not in effect,” the study said.

Curing Signature Issues

In other words, just as there are human factors on the voters’ end that can result in mailed-out ballots not being accepted and counted, there also are human dimensions to how the election administrators act—or do not act—on behalf of the voter.

Nationally, there are currently 19 states that have a process where voters are to be contacted by local election officials and given a short time to resolve the signature—usually by coming into an election office and submitting a form to update their signature on file. California is among those states.

The CVF study suggests that more than half of the voters contacted will follow through to ensure their votes are counted. Statewide, the “cure” rate for signature mismatches was 52.9 percent in 2018, the study said. That rate was because “California laws for signature curing were evolving in 2018.”

The report also noted new ballot-tracking software will allow voters in some California counties to follow their absentee ballot through the application and delivery process, much like people can track packages after online purchases. (Other states are also debuting these tools.)

That tracking tool will make the absentee ballot process less opaque. But as the CVF report highlights, voters should be aware of the human causes why their ballots are rejected, starting with errors made by voters in the youngest and oldest age groups. Young people’s signatures change. They decide to vote at the last minute. They don’t return their ballot soon enough. And older voters must check that they haven’t skipped anything, starting with their signature on the ballot return envelope.

Also available on: BillMoyers.com, Salon, AlterNet.