2023’s Early Races Show Embrace of Mail Voting Despite Hurdles for Voters

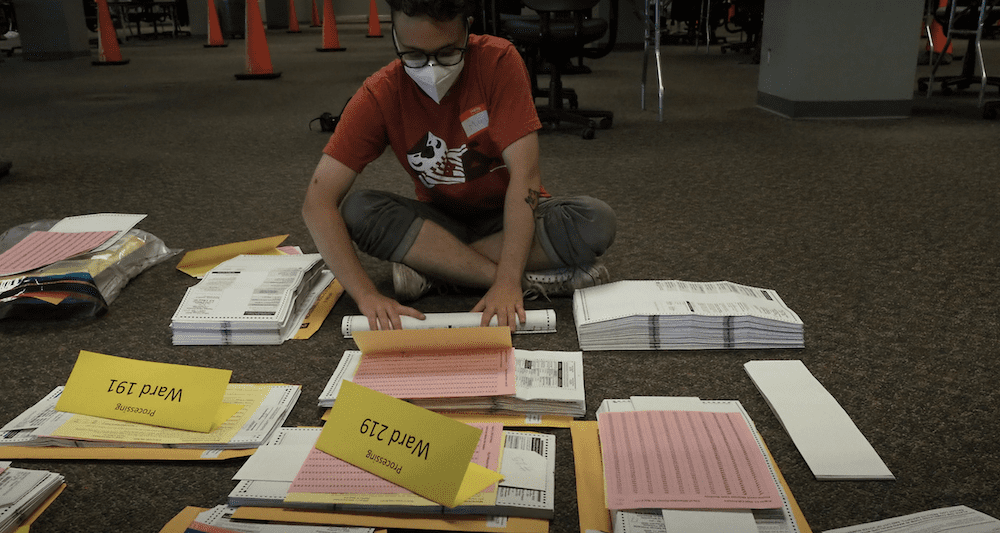

(Milwaukee absentee ballots processed at central count location. Photo by Sue Dorfman / Zuma Press)

Voter turnout never hinges on one factor, as April’s elections show. Wisconsin’s high-profile, high-impact, high-spending contest for the swing seat on its Supreme Court produced the most unexpected of results. In a state whose presidential election margin was 21,000 votes in 2020 and 23,000 votes in 2016, April’s victor, Janet Protasiewicz, a liberal judge, won by more than 200,000 votes. Her sweep, an 11 percent margin, underscored that deep concerns, namely right-wing abortion bans and other power grabs, did not deter voters, even if Republican litigation since 2020 has impeded Wisconsin’s most convenient voting option.

That voting option is casting a mailed-out ballot. Last summer, Wisconsin’s high court ruled ballot drop boxes were illegal. Voters must return these ballots in person, although not every voting site will accept them. If mailed back, the postmark is irrelevant; they must be received by Election Day. A witness must sign each return envelope. As one official said, “It’s remarkable that people use this option at all because it’s been such a case of technocratic obstructions.” Yet, in April 4’s Wisconsin Supreme Court race, one-fourth of the electorate that turned out, a half-million people, chose this voting option. More than a third of these voters returned their mailed-out ballots in person; to polls or their municipality’s vote-counting center.

Such resilience might be a necessarily learned trait in this battleground state. Wisconsin saw the largest numbers of voters using mailed-out ballots in 2020’s presidential primary. You may recall that Democratic Gov. Tony Evers wanted to postpone that April primary due to COVID-19 transmission concerns. The GOP balked and sued. At the last-minute, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against Evers, prompting one of 2020’s most understaffed and chaotic Election Days. Still, many voters, at the urging of election officials, voted early by mail. Thus, in a Supreme Court race that will tip the balance in state rulings about reproductive rights, partisan gerrymanders, and other GOP power grabs and culture war issues, it is unsurprising that voters have learned how to bypass partisan barriers and that 11 percent more people essentially said, ‘Enough!’

Immediately to the south of Wisconsin lies Chicago, where another lesson about convenient voting options could be gleaned from its April 4 election. That runoff’s historic and differently unexpected outcome, coming after a February 28 mayoral election where no candidate won a majority, saw a victory by a progressive, Brandon Johnson, over an establishment Democrat, Paul Vallas. The quick takeaway was that thousands of younger voters, ages 35 and below, could take a sizeable slice of the credit because their turnout on April 4, compared to February 28, helped pushed Johnson across the finish line.

“The February 28th election was driven more by voters 55 and up,” said Max Bever, Chicago Board of Election Commissions spokesman. “On April 4’s election, there were quite a few voters showing up under 55. But especially, we saw improvements with voters ages 18 to 24. There were 5,000 more voters within that age group. That’s probably going to improve with more mail ballots coming back [and being counted after Election Day]. The biggest increase was voters ages 25 to 34. It was 17,000 more voters within that age group compared to the February 28th election.”

The Associated Press called the race on April 4 after Johnson was ahead by 26,000 votes. (The results are not official until the canvass is complete.) Chicago’s convenient voting options, especially surrounding mailed-out ballots, stand in contrast to Wisconsin’s. While both jurisdictions offer early in-person voting in central locations, Chicago has ballot drop boxes at every early voting site (one per ward and at a big downtown vote center). Bever said half of the runoff’s mail-ballots were returned that way. Unlike Wisconsin, Illinois accepts and counts ballots for two weeks after Election Day, as long as the postmark is by Election Day.

When asked whether any of the three voting options (mail, early in-person, Election Day) could be tied to an increase in turnout by any key slice of the runoff’s electorate – such as younger voters, Bever didn’t think so, but he took a closer look. It is possible to glean some demographic data, such as sex and age of voters, from registration files of people who cast ballots. It turns out that voters across all age groups appear to be gravitating to whatever early voting option they think is most convenient.

“It’s becoming clear that we have a similar amount of voters for the elections that we have, but more voters are using early voting and voter by mail,” Bever said. “In the November 2022 election, 53 percent of people still waited to vote on Election Day. Instead, for this February 28th election, it shook out that 23 percent of the people early voted. Nearly 30 percent of the people voted by mail. And only about 47 percent of the people voted on Election Day.”

When comparing the February 28 statistics to the April 4 figures, the early voting patterns were reversed. More than 55,000 more people voted early in-person for the mayoral runoff, while a few thousand fewer people voted with mailed-out ballots. In February, more than 311,000 Chicagoans voted these two ways, compared to about 364,000 in April.

What would account for that change? Perhaps the leadup to the runoff was shorter than the February election. Perhaps the contest between different wings of the city’s Democratic Party was locally exciting. Perhaps organizers were encouraging young voters to vote early and in person – so any issues with getting a ballot could be resolved then and there. (Some of the biggest increases in the runoff’s early in-person voting by voters 55 and younger.)

There is no single explanation for turnout. But in Chicago and nearby Wisconsin, sizable slices of the electorate want to cast ballots before Election or receive them at home. And they appear to navigate whatever steps are required, arduous or not, to vote.