Disability Rights Advocates Press Senate for Internet Voting Option in Voting Reforms

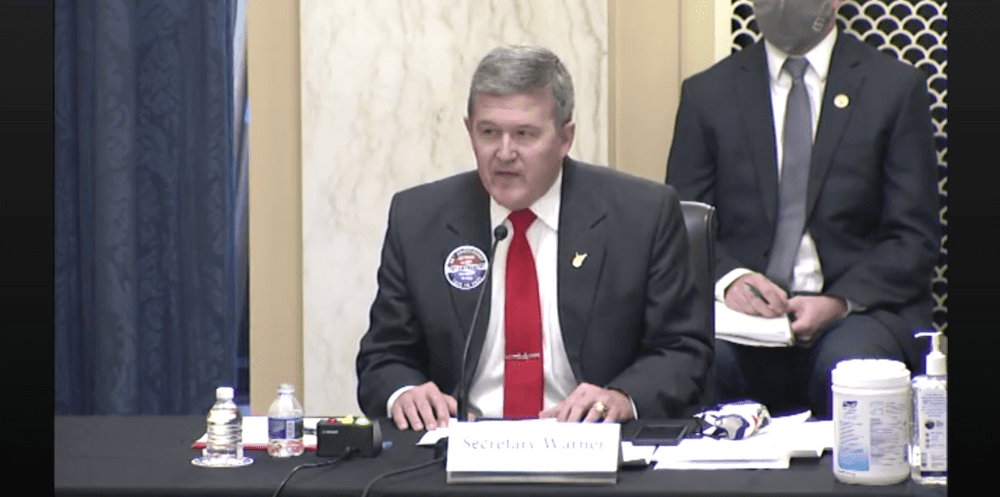

(West Virginia Secretary of State Mac Warner testifying at Senate Rules Committee on S1. Image: https://www.rules.senate.gov/hearings/s1-the-for-the-people-act)

National disability rights organizations are urging the Senate to revise the massive House-passed election reform bill to allow an internet-based voting option for their constituents, who represent one-sixth of the national electorate, and to recognize online voting as a federally sanctioned and regulated voting technology.

Their concerns and online voting remedy have come into focus in recent months as upwards of 20 organizations representing voters with hearing, visual, cognitive and mobility impairments and sometimes requiring assistive technologies have formed a national coalition to press for more flexible voting options as Congress considers the most sweeping reforms in years.

The push for congressional approval of online voting could pose one of the most significant challenges yet for passage of the Democrat-drafted package. It pits two core constituencies—disability rights groups and cybersecurity advocates—against each other. These two cadres have clashed in the past when disability advocates successfully pressed Congress to spend billions on paperless voting machines in the early 2000s, the very systems that most states replaced after Russian interference in 2016’s election due to cybersecurity threats.

“This has been a vexing problem for a long time,” said Ion Sancho, who served for 28 years as supervisor of elections of Leon County, Florida, and retired after the 2016 election. “It’s been a touchy and difficult issue for elections administrators for as long as I can remember.”

The Push for Accessible Voting

The National Coalition for Accessible Voting’s concerns begin with the mandate in the For the People Act of 2021 requiring that voters use a paper ballot. For most voters, that means hand-marking a ballot or using a touch screen computer that prints a filled-out ballot. Every poll also has at least one additional console specially designed for people with disabilities, which the disability rights advocates say draws unwanted attention and does not assist all of these voters.

In recent months, as the Democrats’ major election reform bill has moved through Congress, the disability rights advocates have supported the bill’s broad goals while also sharpening their critique and specifying proposed solutions, including calling for the option to vote online. Initially, their critique focused on the legislation’s paper-ballot mandate.

“Paper-based ballot voting options have become the preferred voting system to many who believe mandating the use of paper ballots is necessary to ensure the security of our elections,” said a January 29 statement by the National Disability Rights Network and other groups. “However, it must be made abundantly clear, that the ability to privately and independently hand mark, verify, and cast a paper ballot is simply not, and will never be, an option for all voters.”

As the Senate Rules Committee began its review of the legislation in March, Curtis L. Decker, the National Disability Rights Network’s executive director, wrote to the panel and said that current federal law did not ensure sufficient voting options for Americans with disabilities,—a group that includes “up to 56.7 million people,” or “one-sixth of the total American electorate, during the 2020 elections.”

“No paper ballot voting system today, ready for widespread use, is fully accessible. Even BMDs [computerized ballot-marking devices] require voters with disabilities to verify and cast a paper-based ballot, which does not ensure a private and independent vote,” Decker said. “A fully accessible voting system by Federal law must ensure the voter can receive, mark, verify, and cast the ballot without having to directly visually inspect or handle paper. Most, if not all, market-ready voting systems cannot do this.”

The national coalition’s remedy is to amend the reform bill to allow people with disabilities—as well as overseas civilians and military personnel (who are covered under a different federal law)—to vote remotely on an accessible device, which means a computer or smartphone. In addition, Congress should include online voting among the voting systems that are federally sanctioned, regulated, studied and funded.

“The option to vote remotely is necessary for some voters with disabilities and improves access for voters to cast their ballot because they do not have to travel to a polling place, which can be a barrier for some voters,” the coalition said. “Unfortunately, remote voting is inaccessible when a voter-verified paper ballot is mandatory, even though accessibility is a legal right.”

There have been news reports about the difficulties of Democrats potentially breaking rank and threatening the chance to pass the massive election reform bill. However, the emerging demands by disability rights advocates could add a new hurdle. It revives an old divide in election circles, pitting disability advocates against cybersecurity advocates.

Nearly two decades ago, these two factions deeply disagreed over what kind of technology should replace the paper punch cards that led to Florida’s presidential election meltdown in 2000. Today, with technologists such as Apple CEO Tim Cook telling the New York Times that people should be able to use their smartphones to vote, the disability advocates are not just seeking an exception from the For the People Act’s paper-ballot mandate; they are seeking to prevent Congress from stifling hoped-for innovation—developments that the election world’s cybersecurity experts say are not possible with today’s internet.

“Understandably, confusion still exists as to why any paper-ballot mandate is harmful to some voters,” said Erika Hudson, a National Disability Rights Network policy analyst. “We share with folks all the time that we simply do not know what technology will look like in five, 10 years… If in a couple of years, when experts develop new, more secure, and accessible voting technology, we should not be bound by a paper ballot mandate.”

An Old Debate Resurfaces

The disability rights organizations’ push for paperless voting is not new. After Florida’s 2000 election, where paper punch-card ballots failed to clearly register voter intent and threw the results into disarray—leading the U.S. Supreme Court to intervene—some disability advocates teamed up with a major voting system manufacturer to lobby for paperless voting machines.

Back then, as today, the advocates’ priority was using machinery with minimal-to-no assistance, which preserves their voters’ privacy, dignity and equality with other voters. The organizations were persuasive in the congressional response to Florida’s meltdown. When the Help America Vote Act (HAVA) was passed in 2002, it included several billion dollars to help states to acquire all-electronic voting systems, called DREs or direct-recording electronic machines. HAVA also required that all polls had at least one station to assist voters with disabilities, with specialized features to help visually impaired people. For years after HAVA’s passage, top-ranking House Democrats like Maryland Rep. Steny Hoyer lauded HAVA’s benefits for this community.

Typically, voting systems are replaced once a generation. During the HAVA debate and since, computer scientists criticized paperless voting systems as problematic. They largely have been proven right. The DREs offered no way to recover lost votes when memory cards failed. They offered no meaningful way to conduct recounts. Their off-the-shelf parts offered little security protection. This cadre of academic critics, which created the advocacy group Verified Voting, initially called for returning to paper-based voting systems. But neither Congress nor states were willing to spend the billions to do so. That status quo changed in 2016 with Russia’s hacking of the Democratic National Committee, penetration into Illinois’ state voter registration database and a Florida contractor who programmed voting machines. Suddenly, an insider debate was transformed into a national security threat demanding action.

Even though federal officials have since repeatedly said that no votes were altered in 2016’s election, Russia’s actions had consequences. They led the federal government to designate voting systems as critical infrastructure. They expanded cybersecurity assistance to help states. And most states installed a new generation of paper ballot-based systems before 2020’s elections.

The academics who opposed all-electronic voting systems also turned their attention to online voting, which was drawing venture capitalists’ interest. The critics worked with government panels assessing voting system technology and helped draft reports saying that online voting would not be secure for the foreseeable future and should be avoided.

At the same time, however, a handful of state and county governments began working with startups and testing using a smartphone as a ballot-marking device. The first pilots were with military voters and then people with disabilities. Those pilots—in West Virginia, Utah, and elsewhere—involved dozens, then hundreds of voters, not millions. They were well-received by voters and were not hacked.

Still, the opposition to online voting is as fervent as the push for remote voting by the disability rights community. Knowing this history and the emotional stakes of this debate, several longtime members of the cybersecurity cadre did not want to be directly quoted. But one cybersecurity expert said, attesting to how deep-seated this divide is, that online voting can never be secured.

“It’s not going to happen in a couple of years. And it’s not going to happen in 10 years,” the expert said. “We have been saying this for 20 years now, and it’s been true all along: if anything, the situation [with online threats] is getting worse, and we have to get that message across. The internet is a more toxic place than it has ever been before.”

Republican Support for Online Voting?

Whether online voting can ever be sanctioned by federal law is one question. At the Senate Rules Committee’s March 24 hearing, the first Republican witness to testify, West Virginia Secretary of State Mac Warner, began his remarks by touting his state’s smartphone pilot for overseas troops, which he later expanded to voters with disabilities.

“My most vehement objection to this [S. 1] is that by prohibiting the electronic transmission of ballots, it strips the most efficient and secure form of voting for our military, the people who put their very lives on the line for our democracy and way of life,” Warner said. “When I was deployed, as were my two sons, my two daughters, my two sons-in-law, all of whom served in the U.S. Army… they have had difficulty voting. Therefore, when I became secretary of state, I was determined to fix this, and we did it through electronic transmission of ballots, using mobile devices. We proved the technology with our military, and then we extended it to voters with disabilities, giving them not just the right to vote but the opportunity to vote.”

When Sen. Shelley Moore Capito, R-West Virginia, asked questions about an hour later, she returned to how the state “pioneered” efforts to offer mobile voting.

“The specific thing I would like to talk about is your mobile voting app,” Capito said, turning to Warner. “You’ve talked about your overseas service members with electronic voting. But I think it’s also important to know that you’ve expanded the use of—with the help of the legislature, I believe—online voting for disabled individuals. And I’ve heard from our deaf and blind community in West Virginia, about what S. 1 would do to prevent them from using this tremendous increased accessibility voting option that you’ve pioneered.”

When considering the politics surrounding the Senate passage of S. 1, West Virginia’s other senator, Democrat Joe Manchin, will have outsized influence. Not only has he opposed any change in the Senate rules to pass the bill—namely modifying the filibuster—but he also has called on fellow Democrats to work with Republicans to pass bipartisan election reform in an April 7 commentary in the Washington Post. “I have always said, ‘If I can’t go home and explain it, I can’t vote for it,’” he wrote, underscoring his fealty to his state’s election officials.

The disability rights community’s proposals to fix the For the People Act include creating a “carve out,” which is a legal exception, to allow their constituents—and overseas civilian and military voters—to use remote devices to receive, mark and cast ballots, which is internet voting. How many voters would actually seek this option, at least initially, has been the subject of research that was recently published by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC).

In the February report, “Disability and Voting Accessibility in the 2020 Elections,” from Rutgers University professors Lisa Schur and Douglas Kruse, “1,782 citizens with disabilities and 787 citizens without disabilities” were asked about voting last year and about their preferred methods of voting in 2020 and for the future.

About three-fourths of voters with disabilities either voted early in person or by mail in 2020, a slightly higher percentage than other voters. Overall, turnout for voters with disabilities was about 7 percent lower than other voters, with the largest gap among visually impaired (11.6 percent) and cognitively impaired (10.3 percent) voters.

“About one in nine voters with disabilities encountered difficulties voting in 2020,” the EAC’s key findings said. “This is double the rate of people without disabilities, but a sizeable drop from 2012… During a general election that experienced a shift to mail and absentee voting, 5 percent of voters with disabilities had difficulties using a mail ballot, compared to 2 percent of voters without disabilities.”

Deep in the report, on Table 24, voters were asked how they wanted to vote in the next election. Among voters with disabilities, 7.8 percent wanted to “vote fully online, using personal computer or smartphone,” and 4.1 percent wanted to “fill out [a] ballot online, print it and mail.” Among voters with no disability, 12.2 percent wanted to vote fully online and 3 percent wanted to fill out the ballot online and return it.

How the disability rights’ community’s push for an online voting option plays out is an open question, as is the fate of the Democrats’ massive election reform bill. But these advocates have signaled they will be standing up for their constituents and pressing lawmakers who oppose expanded accessibility, including an online voting option.

“It is vital that voters with disabilities, who require technology to exercise their right to vote, must be afforded that opportunity,” said the National Disability Rights Network’s Erika Hudson. “If not, we must all be prepared to explain to some voters with disabilities why a paper-ballot mandate outweighs their right to a private and independent vote.”