500 Voting Bills Await State Legislators; 100 Would Make Voting Much Harder

(Photo: Steven Rosenfeld)

Across the country, more than 500 election reform bills are pending in state legislatures. Eighty percent of these bills seek to put into law many of the temporary measures that helped voters in response to 2020’s pandemic. The balance would roll back last year’s emergency measures or more deeply police voting.

The list of bills was compiled by the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law, whose Voting Laws Roundup 2021 report tracked and categorized bills that have been introduced, refiled or carried over from past legislative sessions.

“After historic turnout and increased mail voting in 2020, state lawmakers are pulling in opposite directions,” the report said. “New legislation reflects a surge of bills to limit voter access, with a particular focus on mail voting and voter ID. At the same time, other bills would cement pro-voter policies implemented temporarily last year.”

Most of the restrictive efforts concerned voter registration, a voter’s access to a mailed-out ballot, and the options and requirements associated with returning mailed-out ballots. On the other hand, while there are 106 restrictive bills, 406 bills would expand access to a ballot or codify many of the emergency measures taken by states to assist voters.

“The 2021 legislative sessions have begun in all but six states, and state lawmakers have already introduced hundreds of bills aimed at election procedures and voter access—vastly exceeding the number of voting bills introduced by this time last year,” said the report, which was published on January 26, 2021.

Expanding Participation

On the inclusion side of this ledger, the most prevalent legislation would permit all voters to receive a mailed-out (or absentee) ballot without satisfying an excuse, such as an illness, work conflict or travel. There are related proposals requiring local officials to contact voters who err when filling out their ballot return envelopes to fix those errors so their votes can be counted. There is also legislation to authorize or require officials to use drop boxes for returning these ballots, as well as legislation that allows officials to start vetting ballot envelopes sooner.

There are a handful of states where most or all of these options have been introduced. These steps are part of an overall system of verifying a voter’s eligibility while making it easier for voters to participate in elections and for officials to administer elections. These states include Connecticut, Indiana, Kentucky, Missouri, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York and Texas.

States with Democratic-majority legislatures and governors will be more receptive to these reform packages, while GOP-majority legislatures and governors are less likely to adopt them. However, that blue-red divide is not as fixed in states where both parties hold state offices.

Missouri, for example, which saw political battles in 2020 over expanding access to a mailed-out ballot as the pandemic struck, is less likely than Kentucky to endorse these inclusionary measures. In 2020, Kentucky’s Democratic governor and Republican secretary of state worked together to ensure ballot access during the pandemic. Its fall election was praised as well run, although, as often happens, partisans questioned the accuracy of some results.

Early voting is the next most frequent focus of 2021 legislation. Fourteen states have bills to expand that voting option or to introduce it for the first time. These states span the spectrum, from blue states with historically difficult voting rules, such as New York, to red states such as Alabama, Indiana, Tennessee, South Carolina and Texas. Purple states such as Virginia and Pennsylvania also have bills to expand early voting.

Going further upstream in the process to the starting line, 13 states have bills to implement same-day voter registration and voting. (These states are Alaska, Delaware, Florida, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina and Texas.) Eleven states have legislation to automatically register their voters, following the adoption of automatic voter registration (AVR) in the District of Columbia and 19 states in the past six years. (The proposed AVR states are Florida, Hawaii, Iowa, Indiana, Kentucky, Missouri, Mississippi, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania and Texas.)

Restoration of voting rights for felons is another priority. Fifteen states have introduced bills to restore voting rights or ease restrictions. In 2018, Florida’s voters passed Amendment 4, which re-enfranchised more than 1 million felons. However, its GOP-led legislature and Republican governor required those felons to pay back court fees before voting, which disenfranchised most of these individuals in 2020 and was seen as a factor helping Republicans to maintain statewide power. (The proposed rights restoration states are Alabama, Connecticut, Iowa, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia and Washington.)

“The Sentencing Project estimates that Mississippi disenfranchises over 214,000 citizens living in the community—more than 54% of whom are Black—because of past convictions,” the Brennan Center report said.

Rolling Back Voting

While comprising only 20 percent of the proposed reforms, bills to make voting more difficult—compared to the options offered last fall—have gained the most attention. The Brennan Center said that the volume of 2021 bills represented “a backlash” to 2020’s record voter turnout, and to last year’s historic expansion of absentee and early balloting.

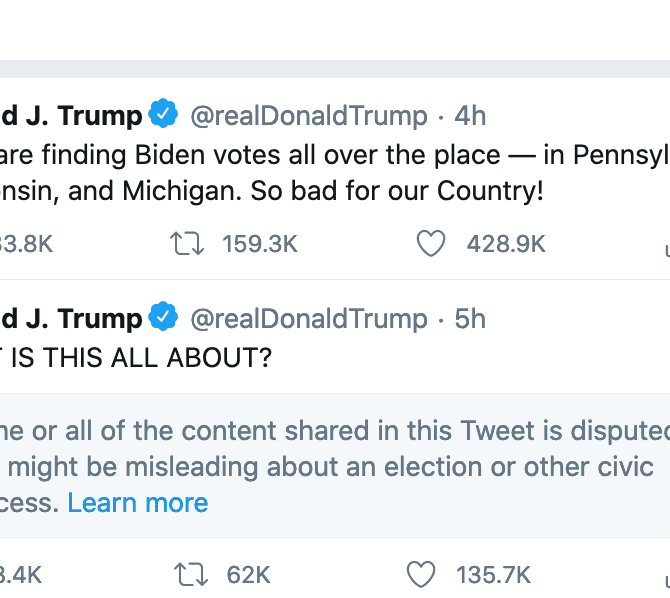

“In a backlash to historic voter turnout in the 2020 general election, and grounded in a rash of baseless and racist allegations of voter fraud and election irregularities, legislators have introduced three times the number of bills to restrict voting access as compared to this time last year,” the Brennan Center said. “Twenty-eight states have introduced, prefiled, or carried over 106 restrictive bills this year (as compared to 35 such bills in fifteen states on February 3, 2020).”

There are four focal points to these restrictive measures: limiting access to a mailed-out ballot; imposing new or stiffer voter ID requirements for returning a mailed-out ballot; limiting voter registration; and enabling more aggressive voter purges.

The states with the most regressive bills are Pennsylvania (14), New Hampshire (11), Missouri (9), Mississippi (8), New Jersey (8), and Texas (8). Georgia also has numerous bills: “lawmakers reportedly plan to introduce bills to require an excuse to cast an absentee ballot, mandate photo ID when returning an absentee ballot, and ban ballot drop boxes, among other harsh restrictions,” the Brennan Center’s report said.

The biggest focus concerns voting with mailed-out ballots, which 65 million Americans used last fall. After the pandemic broke, states suspended the requirement that voters needed to satisfy an excuse requirement to get an absentee ballot. Three states—Pennsylvania, Missouri, and North Dakota—seek to revive their excuse requirement. “[T]hree different proposals in Pennsylvania seek to eliminate no-excuse mail voting, a policy just adopted in 2019,” the Brennan Center said.

Another feature of absentee voting is what is called the permanent absentee list. These are voters who automatically receive ballots by mail. Typically, the voters are seniors, people with disabilities and overseas civilians and soldiers. There is legislation in Arizona and New Jersey to “make it easier for officials to remove voters” from this list, the Brennan Center said. A related voting option is the “permanent early voter list,” which is targeted for elimination by bills in Arizona and Pennsylvania. While Republicans back these proposals, their base—especially in retiree-rich Arizona—has long favored voting by mail or voting early.

Related targets of legislation are groups and individuals who try to help voters obtain absentee ballots and return them. Advocacy groups would face restrictions with mailing absentee ballot applications to voters under bills in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Texas and Washington. (In 2020, some pro-Democratic groups made mistakes with sending voters absentee ballot applications, leading to criticism from local election officials and Republicans.)

There are additional proposed restrictions on who can help voters to cast mailed-out ballots. In Arizona, current law limits such assistance to family and household members. A proposed bill would add an ID requirement for those returning the ballots for another person and require that these absentee ballots be notarized. Alaska, South Carolina and Virginia also have bills that require returned mail ballots to be notarized first. A Virginia bill would require the absentee ballots to be returned at registrars’ offices, which would eliminate the use of drop boxes.

There are also bills expanding the reasons for the disqualification of returned ballots. A Pennsylvania bill would impose signature-matching requirements that are used to vet voters—by how they sign the outside of their ballot return envelope—before their votes are counted. There are ways that checking signatures can be done scientifically, but it can also be done in ways that end up mistakenly disqualifying valid votes. The more professional processes match the ballot envelope signature with a mix of signatures in other state records—from voter registration forms, absentee ballot applications, drivers’ licenses, tax returns, etc.

Under the umbrella of bills that could expand disqualification, Kansas and Pennsylvania also have legislation to reject any absentee ballot that arrives after Election Day, even if it was postmarked before Election Day. An Iowa bill would require voters to mail all ballots at least 10 days before Election Day.

Nearly 36 million people voted early in the 2020 general election. Another wave of proposed legislation would impose more stringent requirements for early in-person voting.

Ten states have introduced voter ID bills, including six states that do not now require early voters to show ID to get a ballot (Minnesota, Nebraska, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Washington and Wyoming). Two states, Mississippi and New Hampshire, would narrow the range of accepted IDs, including those often used by students. A related bill in New Hampshire would eliminate the state’s same-day registration and voting option, which thousands of students use for its presidential primaries. GOP bills in Connecticut, Montana and Virginia would also eliminate same-day registration.

Finally, there are a handful of bills that, if passed, could create big bureaucratic problems. A Texas bill would strip “voter registration authority from county clerks and requir[e] the secretary of state to send voter registration information to the Department of Public Safety for citizenship verification.” That scenario is troubling because the Public Safety agency would have to vet hundreds of thousands of voters, a process that is outside of its mission and expertise.

Similarly, three Mississippi bills would require the state to compare its voter rolls to other data lists to identify non-citizens, and “would require removal from the rolls of voters who fail to respond to a notice within 30 days with proof of citizenship,” the Brennan Center reported. Depending on the database used to verify voters, many false positives (non-citizens) could be generated. Lawsuits from former President Trump’s supporters made similar claims of non-citizen and illegal voting, but never produced authoritative evidence in court.

States and Congress

The fate of the proposed legislation will largely depend on which political party controls state government. Currently, 38 states are controlled by one party that has a legislative majority and the governor’s seat, according to Ballotpedia—15 are Democratic; 23 are Republican. In these “trifecta” states, such as blue Virginia and red Texas, it is unlikely that bills proposed by the minority party will have traction. On the other hand, states with split party rule—such as Pennsylvania where the governor is a Democrat, and the legislature is in GOP hands—may experience nasty fights. But the state’s legislature cannot override a gubernatorial veto.

How state legislatures handle election reforms will provide a very important legal baseline for whatever federal reforms might emerge from Congress in 2021. Currently, both chambers in Congress have teed up a massive reform bill drafted by Democrats for early action. The bills include many of the inclusionary reforms being pushed in the states. The federal legislation is written so court challenges could only apply to narrow policies—one at a time and not the whole bill—if successful.

Needless to say, Republicans are likely to challenge federal reforms passed by Democrats. In 2020, Republicans suing on Trump’s behalf argued that the U.S. Constitution only authorized state legislatures—not governors, secretaries of state, or state supreme courts—to set the rules for elections. Reforms passed by blue state legislatures could be fortified if that “originalist” argument gained traction in federal court. But the converse is true as well. Red states rolling back voting options would also be sustained if that controversial legal theory was upheld in federal court—or by an expanded conservative majority on the Supreme Court.

The most that can be said at this stage in the process—as state legislatures and Congress begin their sessions—is the options and rules for voting into the foreseeable future are in play. Voters can see which political party controls the legislature and governorships in their states to game the likely success of the proposed reforms. For non-trifecta states, voters can take a closer look at whether a governor’s veto can be overridden by the legislature.