Democrat and GOP Leaders Are Considering Online Voting in Light of Coronavirus for Party Elections

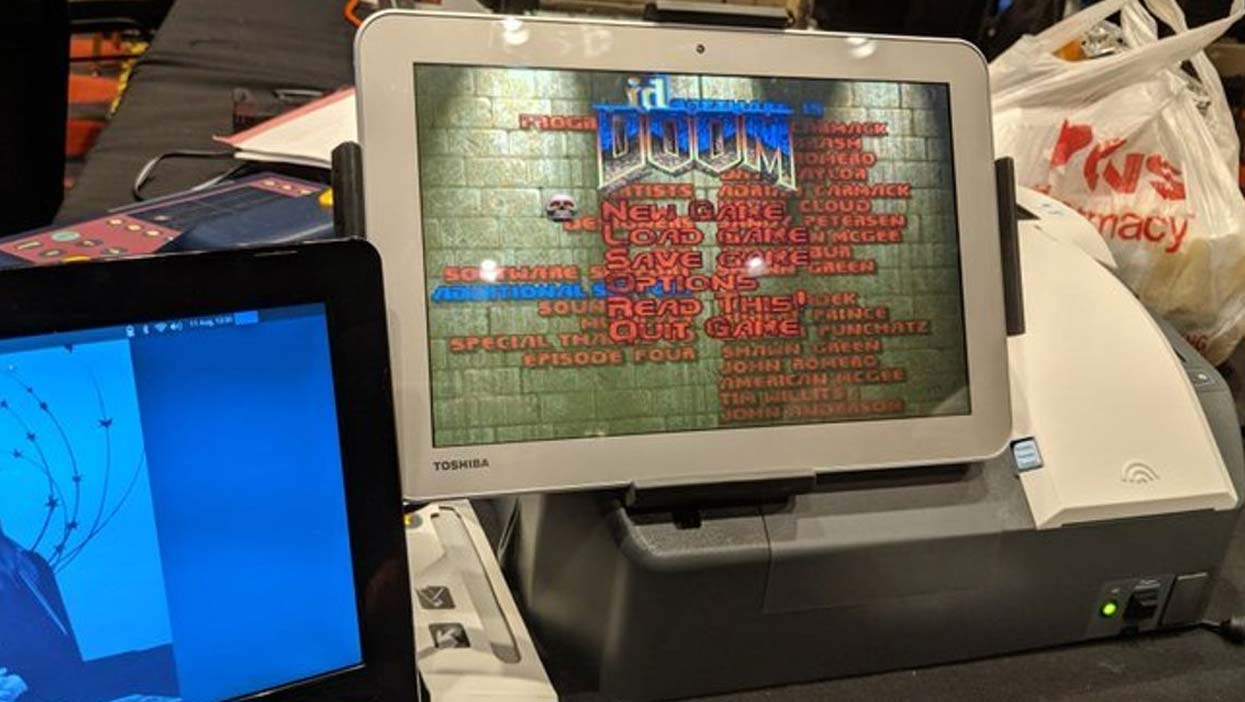

An “electronic pollbook” modified by Def Con hackers to play the computer game Doom. (Twitter)

“I don’t think anyone, in the next month or two months, is planning on doing it [participating] in person.”

This article was produced by Voting Booth, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Online voting is emerging as a near-term solution for state political parties to continue party-run 2020 contests in response to the pandemic, a notable contrast with efforts in government-run elections to expand absentee voting.

Democrats in Minnesota, Colorado, Virginia, and Massachusetts and Republicans in Utah have either adopted policies that allow online voting following the outbreak or have been working with consultants to run online elections in the coming weeks.

These elections are not government-run primaries where all voters who turn out cast secret ballots. Rather, they are the next steps in presidential nominating contests, elections to party leadership posts, resolutions and other business.

“Last night, an emergency meeting of the Minnesota DFL [Democratic Farmer Labor] Party Executive Committee made the decision to move local convention activities away from in-person meetings and tele-conventions, and instead conduct party business via an online balloting system,” a March 17 statement by the Minnesota DFL said.

Colorado Democratic “Governor [Jared] Polis signed an executive order and House Bill… [that] allows delegates to vote by email, mail, telephone or app,” a March 17 press release said. The bill also “allows an individual who is physically present to carry up to five proxies [for voters not present], and allows the [state] party to reduce the number of participants required for quorum.”

The Democratic Party of Virginia was studying options that included electronic voting for its upcoming contests, said Virginia-based attorney Frank Leone, who also sits on the Democratic National Committee’s Rules and Bylaws Committee, the panel that oversees its presidential nominating contests.

“I don’t think anyone, in the next month or two months, is planning on doing it [participating] in person,” he said. “We’ve got caucuses in April that we are not going to do, although I think we have some ways around it. We have district conventions in May. We are thinking of doing those remotely and then various ways to address the state convention.”

“I think everybody is trying to figure out ways to do this without having more than 10 people in a room,” he said.

Democrats in Massachusetts and Republicans in Utah were considering using a smartphone-based app, developed by Voatz (which Massachusetts has previously used). While longtime opponents of online voting have criticized the Voatz app as untrustworthy, a half-dozen state parties — mostly Republican — may soon use it, a company executive said without naming all of the states.

An unexpected return

The emergence of online voting options in party contests would raise eyebrows in election policy circles under more normal circumstances, as opponents have been wary of any use of this technology that could validate it for state-run elections.

For example, a pressure campaign has been unfolding in Puerto Rico, where a bill awaiting the governor’s signature would phase in internet voting as a part of a response to recently destructive hurricanes. Opponents are urging a veto.

“Anyone in the world, including foreign nation states, criminal organizations, or our domestic partisans, can attack any Internet voting system, attempt to change votes, violate privacy, or disrupt the election—possibly in a completely undetectable way,” a March 19 letterfrom Verified Voting, a national advocacy group, to Gov. Wanda Vázquez Garced, said. Three-dozen academics, computer scientists, security experts and voting rights activists co-signed the letter.

Government-run elections are not the same as party contests. State-run elections are more regulated, including requiring state or federal certification of the voting systems. Party contests are less so and may not even require secret ballots. They share features with elections for other non-governmental entities, such as labor unions, corporate shareholders or even the Academy Awards.

But party-run contests are in a gray zone between private and public elections because their outcomes affect candidates and government. Thus, developers of new voting technologies have seen party contests as valuable proving grounds.

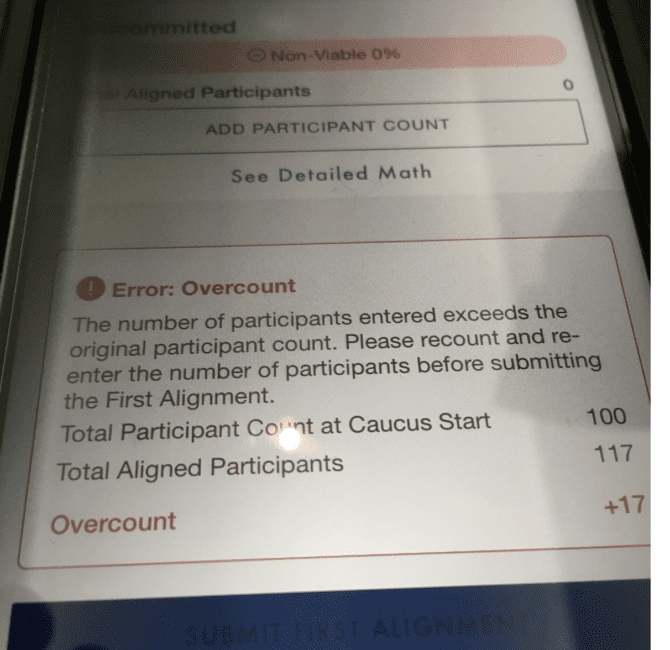

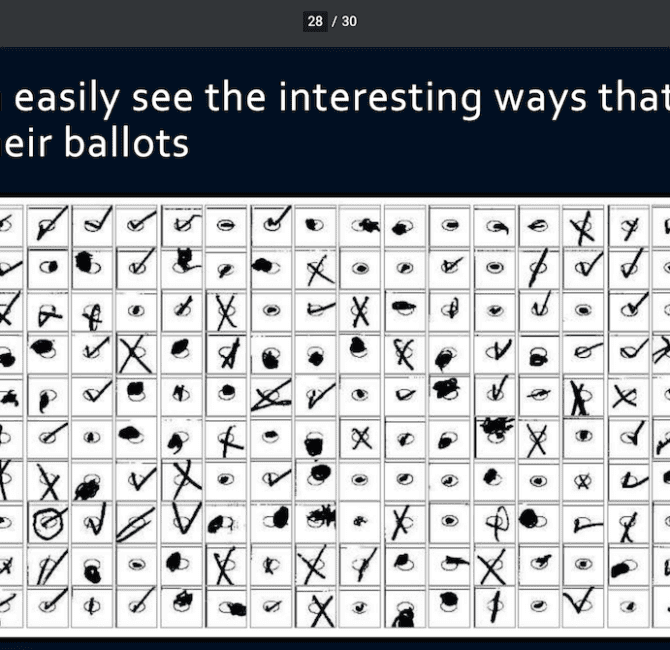

That strategy backfired in the Democratic Party’s 2020 presidential caucuses in Iowa and Nevada, when new digital apps and counting systems did not perform as pledged, delaying the results — followed by questions from some candidates about the reported outcomes’ accuracy.

Before emergencies like the pandemic and Puerto Rico hurricanes, online voting opponents had kept the option out of most government elections. A few exceptions involved trials where a few hundred people — mostly overseas troops and civilians — voted. As a result, Puerto Rico’s legislation has alarmed critics.

Among the signatories to the letter lobbying Gov. Vázquez Garced to veto Senate Bill 1314 were some of the experts who advised the DNC’s Rules and Bylaws Committee in 2019 before the RBC reversed course on requiring its 2020 caucus states to offer a remote participation option (which meant voting online or by cell phone). While virtual voting via phones did not happen, Iowa and Nevada had other problems.

Thus, it is somewhat ironic that a number of state Democratic parties are looking to online voting to continue their 2020 contests, even if these exercises do not involve voting by the general public. However, given the pandemic’s challenges, the DNC Rules and Bylaws Committee would not be scrutinizing the shift to online voting options as it might otherwise do, said James Roosevelt Jr., RBC co-chair.

“As long as it deals with how they will conduct their state convention, it is unlikely that we will look at it,” he said. “To the extent that it deals with the selection of national convention delegates, we might well look at it. Frankly, I think there is likely to be less scrutiny on our part under this state of national emergency than there would have been in normal times.”

The shift to online voting in the nominating process’s next stages — county or state conventions — raises the prospect that some of the voting systems deployed could also be used as a partial replacement for the Democratic National Convention, which is slated for July 13-16 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Roosevelt also said that the DNC was still planning to hold its national convention in July. (The convention was timed to not conflict with the 2020 Olympics, which have not yet been postponed, but countries are saying they won’t send any athletes.)

As some states have moved their presidential primaries to June, Roosevelt said the RBC would review potential delegate allocation changes that possibly could affect the total number needed to nominate a presidential candidate. But the big picture, he said, was that state parties were not “postponing or canceling conventions.”

The RBC co-chair said that he favored any solution that increased access and participation in 2020’s party-run contests and primaries.

Primaries also changing

In response to the pandemic, state officials and election policy experts have been pushing a shift to voting by mail for 2020’s remaining elections. While executing that shift on a national level is a formidable task, Frank Leone said that some blue states were acting quickly to try to increase access in upcoming spring primaries.

In Virginia and New York, where an “excuse” is now needed to get an absentee ballot, state election boards have decided that voters could check a box on an application citing “an illness” — the coronavirus — to get a ballot, he said.

But in purple and red-run states, there are brewing fights over near-term voting options and rules. The Wisconsin Democratic Party and DNC filed an emergency suit on March 18 and won a court order to lift barriers to online voter registration before its April 7 primary. But the Texas Democratic Party has not convinced statewide officials to expand early voting for its May 26 primary runoffs.

The pandemic is changing the way that America votes. But whether online voting will be expanded beyond party contests is an open question. Computer scientists who oppose online voting, including those who signed the letter urging a Puerto Rico veto, said that they expected it to arise in discussions about the pandemic.

“I would suspect the situation is this: Governors and their staff have N+1 things that are critical right now. Someone says, ‘Well, we could just take the election online, and that would solve one of the critical issues,'” Duncan Buell, University of South Carolina Computer Science and Engineering Department chair, said via email. “Thus, a decision would be made to do what seems easy at the time.”

“In this time of pandemic, it is to be expected that the issue will arise many times,” concurred David Jefferson, a computer scientist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, who has studied voting for decades. “I think/hope that election officials are so busy with preparing for a huge surge in mail-in voting that they will not want to take on the additional burden and risk of learning about and fielding online voting.”

Buell and Jefferson said that there were dividing lines when considering online voting’s use. They emphasized that voting for presidential delegates at a national convention — or even Congress voting remotely — was not the same circumstance as all of an election district’s voters casting secret ballots.

“It is not just nonsecrecy that allows online voting,” Jefferson added. “It should actually be public who voted and for what. Only that way can all voters verify that their ballots were correctly cast, and everyone can verify that only eligible voters are listed as having voted — and at most [voting] once, and everyone can verify the outcome.”

And any online system also has cybersecurity risks, he said, where meddlers could seek to disrupt the process or corrupt the results.

“To prevent other kinds of mischief, it is important to have strong authentication of the voters, e.g., through two-factor authentication such as a password and RSA token,” he said. “And any online voting system is still vulnerable to denial of service attack, so there are still risks.”

Indeed, every voting system has risks. The question has always been: Do the benefits outweigh the liabilities? In an unexpected pandemic, online voting options, once scorned, are being reassessed with that equation.

Also Available on: www.salon.com