Did the Contested Kentucky Election Reveal Republicans’ Strategy for 2020?

(Photo / facebook.com/mattbevinforkentucky/photos)

Kentucky’s 2019 governor’s race has showcased two troubling political tactics that may come into play in 2020 if the presidential election is seen as coming down to the wire in red-run swing states.

The first trend was an outbreak of online disinformation immediately after Election Day seeking to create doubt about the likelihood of a Democratic victory. In this case, it was the election of Democrat Andy Beshear as the state’s next governor after leading by 5,100 votes in the early unofficial returns.

The disinformation’s linchpin was the oft-hurled Republican cliché that Democrats had voted illegally in numbers that stole the race — never mind that the GOP swept every other statewide office. This go-to accusation has surfaced in many close elections in recent years, whether Donald Trump’s popular vote loss to Hillary Clinton in 2016, Florida’s U.S. Senate race in 2018, North Carolina’s governor’s race in 2016, and elsewhere. (In North Carolina, a Republican operative was caught stealing ballots, forcing a do-over election of a 2018 U.S. House race.) More than a week after Kentucky’s election, the incumbent Republican governor, Matt Bevin, hasn’t conceded nor produced any evidence of voting “irregularities.”

But the more ominous tactic is what followed Bevin’s accusations as allies in the state’s legislature floated a pro-GOP remedy not seen in recent years. That prospect was the notion that the legislature could override the popular vote to appoint Bevin to another term — a response to the purported problematic voting granted by the state’s constitution.

The Kentucky Constitution gives its legislature such power, which it last used in 1899. In recent days, evidence supporting Bevin’s allegations has not been forthcoming. That’s prompted growing numbers of Republicans to say that Bevin should move on. (There also are court decisions that have ruled that states cannot change election rules after a vote.)

Yet the notion that Republicans could seek to subvert elections by moving those contests from voters to legislatures where they have supermajority control is a tactic to note and track. Several potential 2020 swing states have Republican control of legislative and executive branches: Florida, Ohio, Georgia and Texas. While there may be legal hurdles that likely would have collided with such a power grab in Kentucky’s governor’s race, those same precedents do not apply to a presidential election, which is governed by the U.S. Constitution.

In presidential elections, the U.S. Constitution has no requirement that the popular vote result must be followed when legislatures appoint Electoral College delegations. Thus, Kentucky’s governor’s race raises a worrisome question. Could states with red super-majority legislatures back away from a presidential vote and just appoint Electoral College delegations?

“If a state legislature said, today, ‘You know what. We’re not going to bother with voting for president next November. We’re just going to appoint our electors directly. We’re not going to go through the complication of actually having a popular vote.’ I don’t think there would be any federal constitutional objection, unfortunately,” said Ned Foley, who directs the election law program at Ohio State University and specializes in ballot-counting disputes. “I think that it’s absolutely clear that they have the right to do that under [the Constitution’s] Article Two. And that was interpreted that way in the 19th century and in Bush v. Gore.”

These twin trends — escalating disinformation to delegitimize voting and suggesting ways that popular vote outcomes can be preempted — are the red flags raised by Kentucky’s 2019 governor’s race. They reveal how extreme political campaigns have become compared to even the nastiest contests seen just a few years ago, even as they build on those tactics.

How low will tactics go?

Recall 2016, when another Republican incumbent governor, North Carolina’s Pat McCrory, was trailing by 7,000 votes after November’s Election Day. McCrory’s campaign and the state GOP made the unsubstantiated claim that Democrats, led by black political action committees, fabricated votes that put Democrat Roy Cooper ahead.

At that time, state and county election boards — dominated by GOP appointees — not only did not find any evidence of pro-Democratic voter fraud, as the Republican incumbent governor had alleged, but found that a pro-GOP operative had been stealing and filling out absentee ballots in a U.S. House contest. That scandalous finding forced that congressional race to be rerun and led to criminal charges.

As North Carolina’s 2016 post-Election Day review continued, McCrory and top state GOP officials kept claiming that there was fraud and pledged to appeal any setback — until election officials ruled Cooper won. Then, the state’s Republican-led legislature (a product of 2011’s gerrymander) moved to strip Cooper’s gubernatorial authority.

This episode may be considered the “good old days” compared to what has unfolded in Kentucky since November 5th’s election.

After Beshear was ahead in unofficial results, Bevin began making unsubstantiated accusations of illegal voting. As expected, a GOP loyalist paid for automated phone calls asking voters to report suspicious activities or voter fraud to help Bevin’s case. He faced a deadline on November 14 when counties will rerun their tabulations, the next step toward certifying the winner.

But then came the rapid use of disinformation — thousands of people and software robots posting on Twitter—to boost election theft claims as Bevin’s allies looked to their legislature as a legal venue to overturn a popular vote. As Chris Sautter, an election law professor at American University who has worked on high-profile recounts for 30 years, noted, “Forum is one of the most important factors in resolving a disputed election.”

“Claiming there are ‘irregularities’ or that voter fraud explains the unexpected Democratic turnout is an attempt to delegitimize an election won by a Democrat or that Republicans fear will be won by a Democrat,” Sautter said. “If the election seems to be one that either candidate can legitimately claim they won, the case might then move to a more favorable forum… But it is difficult to get the case to a more favorable forum if the public doesn’t believe the election is truly in dispute.”

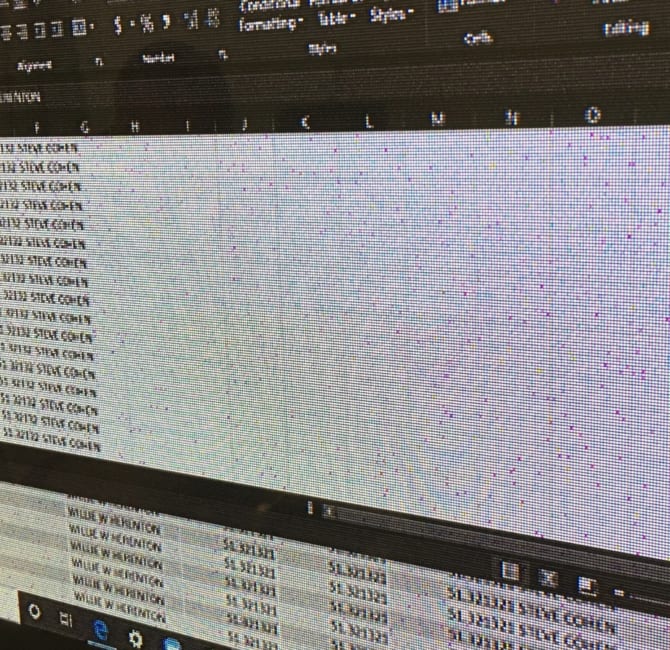

The believability factor is where online propaganda comes in. On November 11, the New York Times detailed how “hyperpartisan conservatives and trolls” — people posting false content — were “providing early grist for allegations of electoral theft in Kentucky.”

The disinformation sought to reframe the narrative. The state’s top election official, Democratic Secretary of State Alison Lundergan Grimes, found one Twitter post about “shredded ballots,” the Times said, which Twitter took down but not before it had been copied and widely shared online. Other posts criticized weak state election laws and voting on electronic voting machines with no paper trail of votes. Some were generated by right-wing law groups. A high-tech consulting firm told the Democratic Governors Association that it had traced disinformation from 1,450 real people and 2,350 robotic accounts on Twitter, each a source of false accounts.

In Kentucky, Bevin’s apparent inability to substantiate his voter theft allegations has led Republicans to distance themselves from that claim and the prospect of their legislature overriding the will of voters—which Ohio State’s Foley said was good news for now.

“The good news is there are limits,” he said. “Even in this current climate, democracy may in fact prevail. That will be a good news story, if the Republicans say that when the Democrats win, you actually have to acknowledge that they won.”

But Sautter is worried that Bevin’s gambit race may open up a dark door if 2020’s presidential election is seen as being very tight in red-run states.

“I believe Trump will do anything possible to win in 2020,” he said. “Having a partisan legislature reverse the outcome of an election that is close but not in doubt would be the next step in the ‘recount wars’ that began with Bush v. Gore. In 2000, the Republican-controlled Florida state legislature made it clear they would side with Bush if it came to that.”

Also Available on: www.salon.com