Election Defenders’ Top 2024 Worry: Online Rumors, Deceptions, Lies Swaying Masses

(Donald Trump at rally in June 2016 in Phoenix, AZ. Photo credit: Gage Skidmore via Wikimedia Commons)

A decade ago, when Kate Starbird dove into studying how rumors spread online and how people use social media to make sense of what is happening during crises, the future co-founder of the University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public had no idea that she would become a target of the darker dynamics and behavior she was studying.

Starbird, a Stanford University computer science graduate who turned professional basketball player, had returned to academia as an expert in “crisis informatics.” That emerging field looks at how people use online information and communication to respond to uncertain and chaotic events. Starbird initially looked at how social media could be helpful in crises. But she and her colleagues increasingly were drawn to how false rumors emerge and spread. They confirmed what many of us have long suspected. Mistaken online information tends to travel farther and faster than facts and corrections. “[B]reaking news” accounts often magnify rumors. People who fall for bogus storylines might correct themselves, but not before spreading them.

Those insights were jarring enough. But as Starbird and her colleagues turned to tracking the post-2020 attacks on America’s elections by Donald Trump, copycat Republicans, and right-wing media, they were no longer looking at the dynamics of misinformation and disinformation from the safety of academia. By scrutinizing millions of tweets, Facebook posts, YouTube videos, and Instagram pages for misleading and unsubstantiated claims, and alerting the platforms and federal cybersecurity officials about the most troubling examples, Starbird and her peers soon found themselves in the crosshairs of arch Trump loyalists. They were targeted and harassed much like election officials across the country.

Starbird was dragged before congressional inquisitions led by Ohio GOP Representative Jim Jordan. Her University of Washington e-mail account was targeted by dozens of public records requests. As her and other universities were sued, she and her peers spent more time with lawyers than students. In some cases, the intimidation worked, as some colleagues adopted a “strategy of silence,” Starbird recounted in a keynote address at the Stanford Internet Observatory’s 2023 Trust and Safety Research Conference in September. That response, while understandable, was not the best way to counter propagandists, she said, nor inform the public about their work’s core insights—which is how mistaken or false beliefs take shape online, and why they are so hard to shake.

“Some colleagues decided not to aggressively go after the false claims that we received about ourselves,” Starbird said—such as accusations that alleged they had colluded with the government to censor right-wing speech. “I don’t think that they should have gone directly at the people saying them. But we needed to get the truth out to the public… Online misinformation, disinformation, manipulation; they remain a critical concern for society.”

Barely a week after November 2023’s voting ended, the narratives dominating the news underscored her point. The reproductive rights victories and embrace of Democrats, led by growing numbers of anti-MAGA voters, had barely been parsed by the public before Trump grabbed the headlines by transgressing American political norms.

In a Veterans Day speech, of all settings, Trump, who is the leading 2024 Republican presidential candidate, attacked his domestic opponents with rhetoric that mimicked European fascist dictators that Americans had defeated in World War II. Trump called his domestic critics “vermin,” and pledged that, if reelected, he would use the Justice Department to “crush” them. Even the New York Times noted the similarity between Trump’s words to Adolph Hitler and Benito Mussolini.

Trump’s outburst was one of many incidents and trends that have led election defenders and propaganda experts to say that their biggest worries about 2024 elections concern the reach of mistaken or deceptive propaganda—misinformation and disinformation—and its persuasive power to shape political identities, beliefs, ideologies, and provoke actions.

“It’s no secret that Republicans have a widespread strategy to undermine our democracy. But here’s what I’m worried about most for the 2024 election—election vigilantism,” Marc Elias, a top Democratic Party lawyer, said during a late October episode of his “Defending Democracy” podcast. “Election vigilantism, to put it simply, is when individuals or small groups act in a sort of loosely affiliated way to engage in voter harassment, voter intimidation, misinformation campaigns, or voter challenges.”

Elias has spent decades litigating the details of running elections. Since 2020, many Republican-run states have passed laws making voting harder, disqualifying voters and ballots, imposing gerrymanders to fabricate majorities, and challenging federal voting law. Democratic-led states have gone the other direction, essentially creating two Americas when it comes to running elections. Notably, this veteran civil rights litigator is more worried about partisan passions running amok than the voting war’s latest courtroom fights. And he’s not alone.

“It’s the minds of voters,” replied Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson, a Democrat, when asked at the 2023 Aspen Cyber Summit in New York City about the biggest threat to the legitimacy of 2024 elections. Benson emphasized that it was not the reliability of the voting system or cybersecurity breaches. “It’s the confusion, and chaos, and the sense of division, and the sense of disengagement that bad actors are very much trying to instill in our citizenry.”

Information and Psychology

There are many factors driving the hand-wringing over the likelihood that political rumors, mistaken information, mischaracterizations, and intentional deceptions will play an outsized role in America’s 2024 elections. Academics like Starbird, whose work has buoyed guardrails, remain under attack. Some of the biggest social media platforms, led by X—formerly Twitter—have pulled back or gutted content policing efforts. These platforms, meanwhile, are integrating artificial intelligence-generated content, which some of these same researchers have shown can create newspaper-like articles that swaths of the public say are persuasive.

Additionally, the U.S. is involved in controversial wars in Ukraine and Israel invoking global rivalries, which may entice the hostile foreign governments that meddled in recent presidential elections to target key voting blocs in 2024’s battleground states, analysts at the Aspen Cyber Summit said. And domestically, federal efforts to debunk election- and vaccine-related disinformation have shrunk, as Trump loyalists have accused these fact-based initiatives of unconstitutional censorship and sued. These GOP-led lawsuits have led to conflicting federal court rulings that have not been resolved, but fan an atmosphere of lingering distrust.

It is “a real concern for 2024: That the feds and others who monitor and inform citizens about lies and false election information will unilaterally disarm, in the face of the constant bullying and harassment,” tweeted David Becker—who runs the Center for Election Innovation and Research and whose defense of election officials has made him a target of Trump loyalists—commenting after November 2023 Election Day.

What is less discussed in these warnings is what can be done to loosen online propaganda’s grip. That question, which involves the interplay of digitally delivered information and how we think and act, is where insights from scholarly research are clarifying and useful.

Debunking disinformation is not the same as changing minds, many researchers at the recent Trust and Safety conference explained. This understanding has emerged as online threats have evolved since the 2016 presidential election. That year, when Russian operatives created fake personas and pages on Facebook and elsewhere to discourage key Democratic blocs from voting, the scope of problem and solution mostly involved cybersecurity efforts, Starbird recalled in her keynote address during the conference.

At that time, the remedy was finding technical ways to quickly spot and shut down the forged accounts and fake pages. By 2020 election, the problem and its dynamics had shifted. The false narratives were coming from domestic sources. The president and his allies were people using authentic social media accounts. Trump set the tone. Influencers—right-wing personalities, pundits, and media outlets—followed his cues. Ordinary Americans not only believed their erroneous or false claims, and helped to spread them, but some Trump cultists went further and spun stolen election clichés into vast conspiracies and fabricated false evidence.

Propaganda scholars now see disinformation as a participatory phenomenon. There is more going on than simply saying that flawed or fake content is intentionally created, intentionally spread, and intentionally reacted to, Starbird and others explained. To start, disinformation is not always entirely false. It often is a story built around a grain of truth or a plausible scenario, she said, but “layered with exaggerations and distortions to create a false sense of reality.”

Moreover, disinformation “rarely functions” as a single piece of content. It is part of a series of interactions or an ongoing campaign—such as Trump’s repeated claim that elections are rigged. Crucially, while propaganda and disinformation are often talked about as being deceptive, Starbird said that “when you actually look at disinformation campaigns online, most of the content that spreads doesn’t come from people—those that are part of it [the bogus campaign], it comes from unwitting actors or sincere believers in the content.”

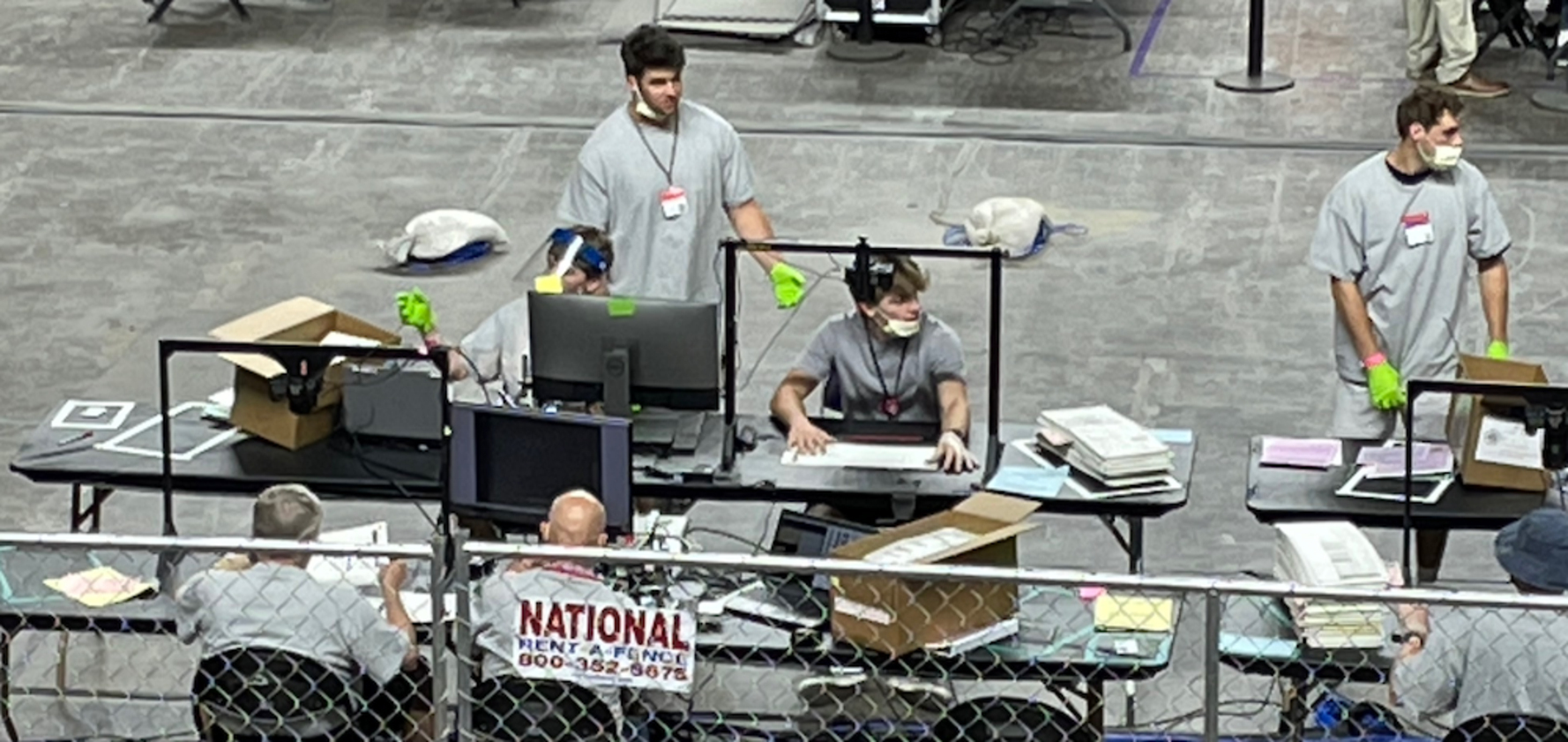

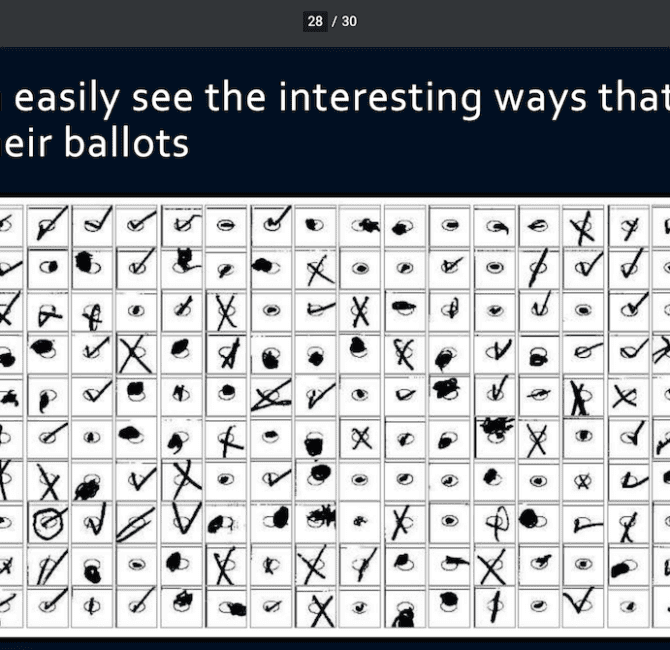

These layered dynamics blur the lines between what is informational and what is psychological. The factors at play include how first impressions, memory, and beliefs can clash with the ground truth—or eclipse it. Starbird cited one example she has studied. In 2020 in Arizona’s Maricopa County, home to Phoenix, Trump supporters had been hearing for months that the November election would be stolen. When they saw that some pens given to voters bled through their paper ballot, that triggered fears and the so-called “Sharpiegate” conspiracy emerged and went viral. Election officials explained that ballots were printed in such a way that no vote would be undetected or misread. But that barely dented the erroneous assumption and false conclusion that a presidential election was being stolen before their eyes.

“Sometimes misinformation stands for false evidence, or even vague [evidence] or deep fakes [forged audio, photos or video], or whatever,” Starbird said. “But more often, misinformation comes in the form of misrepresentations, misinterpretations, and mischaracterizations… the frame that we use to interpret that evidence; and those frames are often strategically shaped by political actors and campaigns.”

In 2023, online influencers do not even have to mention the triggering frames, she said, as their audiences already know them. Influencers can pose questions, selectively surface evidence, and knowingly—in wink and nod fashion—create a collaboration where witting and unwitting actors produce and spread false content and conclusions. Additionally, the technical architecture of social media—where platforms endlessly profile users based on their posts, and those profiles help to customize and deliver targeted content—is another factor that amplifies its spread.

Starbird’s summary of the dynamics of disinformation is more nuanced than what one hears in election circles, where officials avoid commenting publicly on partisan passions. But she was not the only researcher with insights into how and where mis- and disinformation are likely to surface in 2024. Eviane Leidig, a postdoctoral fellow at Tilburg University in the Netherlands, described another conduit during the conference where “personal radicalization and recruitment narratives” may be hiding in plain sight: influencer-led lifestyle websites.

Leidig showed seemingly innocuous pages from influencers that use “the qualities of being relatable, authentic, accessible, and responsive to their audiences to cultivate the perception of intimacy.” As they shared their personal stories, Leidig pointed to instances where influencers’ extreme views filtered in and became part of the community experience. “The messaging [is] to sell both a lifestyle and an ideology in order to build a fundamental in-group identity,” she said, which, in turn, ends up “legitimizing and normalizing… their political ideology.”

The reality that many factors shape beliefs, identity, community, and a sense of belonging means that unwinding false rumors, misconceptions, and lies—indeed, changing minds—is more complicated than merely presenting facts, said Cristina López G., a senior analyst at Graphika, which maps social media, during her talk on the dynamics of rabid online fandom at the 2023 Trust and Safety Research Conference.

López G. studied how some of Taylor Swift’s online fans harassed and abused other fans over the superstar’s purported sexuality—whether she was “secretly queer.” The “Gaylors,” who believed Swift was gay or bisexual, shared “tips about how to preserve their anonymity online,” López G. said. They anonymously harassed others. They used coded language. They censored others. Their mob-like dynamics and behavior are not that different from what can be seen on pro-Trump platforms that attacked RINOs—the pejorative for “Republicans in Name Only”—or anyone else outside their sect.

“Fandoms are really microcosms of the internet,” López G. said. “Their members are driven by the same thing as every internet user, which is just establish their dominance, and safeguard their community beliefs, and beliefs become really closely tied to who they are online… who they identify as online.”

In other words, changing minds is neither easy nor quick, and, in many circles, not welcomed.

“What this means is that real-world events do very little to change this belief,” López G. concluded, adding this observation also applied to political circles. “If you change beliefs, you’re no longer part of that community… So, it’s not really, ‘what’s real?’ and ‘what’s not?’ It’s really the friends we’ve made along the way.”

“Once you begin to see this phenomenon through that lens [where disinformation is participatory and tribal], you realize it’s everywhere,” Starbird said.

‘Counter-influencers’

At the Aspen Cyber Summit, the elections panel offered a sober view of the strategies undertaken during the Trump era, and challenges facing election defenders in and outside of government in 2024.

To date, the response essentially has been twofold. As Chris Krebs explained, “Information warfare has two pillars. One is information technical; the other is information psychological.” Krebs ran CISA—the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency—during the Trump administration. He was fired after 2020 Election Day for retweeting that the election was “the most secure in American history.” As he told the audience, “It was also the most litigated election. The most scrutinized election. The most audited election. I could go on…”

On the “information technical” side, Krebs said that officials have learned to protect election computers and data. There was no indication that anyone manipulated any jurisdictions’ computers in recent cycles. But that achievement mostly took place inside government offices and behind closed doors. It has not been fully appreciated by voters, especially by partisans who do not believe that their side lost.

Instead, what many disappointed voters have seen of election operations has preyed on their insecurities—such as Starbird’s Sharpiegate example. In other words, the technical successes have been offset by what Krebs called “information psychological.” The strategy to respond to this dynamic, he and others said, is to curtail propaganda’s rapid spread on both fronts.

Some of that challenge remains technical, such as having contacts in online platforms who can flag or remove bogus content, they said. But the most potentially impactful response, at least with interrupting propaganda’s viral dynamics, hinges on cultivating what Leidig called “counter-influencers,” and what election officials call “trusted voices.” These voices are credible people inside communities, online or otherwise, who will say “not so fast,” defend the democratic process, and hopefully be heard before passionate reactions trample facts or run amok.

“All the tools we need to instill confidence in our elections exist,” Benson said at the summit. “We just have to get them—not just in the hands of trusted voices, but then communicate effectively to the people who need to hear them.”

But Benson, whose hopes echo those heard from election officials across the country, was putting on a brave face. She soon told the audience that reining in runaway rumors was not easy—and said officials needed help.

“We need assistance in developing trusted voices,” Benson said. “Second, we need assistance, particularly from tech companies in both identifying false information and removing it. We know we’re farther away from that than we have ever been in the evolution of social media over the last several years. But at the same time, where artificial intelligence is going to be used to exponentially increase both the impact and reach of misinformation, we need partners in the tech industry to help us minimize the impact and rapidly mitigate any harm.”

Still, she pointed to some progress. Michigan’s legislature, like a handful of states, recently passed laws requiring disclosure of any AI-created content in election communications. It has criminalized using deep fake imagery or forged voices. Congress, in contrast, has yet to act—and probably won’t do so before 2024. The White House recently issued executive orders that impose restrictions on AI’s use. While the large platforms will likely comply with labeling and other requirements, 2024’s torrid political campaigns are likely to be less restrained.

And so, Benson and others have tried to be as concrete as possible in naming plausible threats. In November, she told the U.S. Senate’s AI Caucus they should “expect” AI to be used “to divide, deceive, and demobilize voters throughout our country over the next year.” Those scenarios included creating false non-English messages for minority voters, automating the harassment of election officials, and generating error-ridden analyses to purge voters.

But countering propaganda remains a steep climb. Even before AI’s arrival, the nuts and bolts of elections were an ideal target because the public has little idea of how elections are run—there is little prior knowledge to reject made-up claims and discern the truth. Moreover, political passions peak in presidential years, and every election cycle has a handful of errors by workers who set up the devices that check in voters, cast votes, and count ballots. This November’s election was no exception, according to this tally of administrative errors by ElectionLine.org. After Trump’s 2020 loss, operational mistakes like these—which caused some votes to be incorrectly counted before the error was found and corrected—were misinterpreted, mischaracterized, and became fodder for his stolen election tropes. Much the same scripts surfaced after this fall’s snafus.

As crisis informatics researchers like Starbird have confirmed, doubt is more easily provoked than trust. Nor do labels and fact-checking alone change minds. At the cyber summit, Raffi Krikorian, the CTO at the Emerson Collective, a charitable foundation—who held that role for the Democratic National Committee during the last presidential election—made the same point.

“Our election system, in a lot of ways, is built on trust—like we trust a lot of the portions of the mechanics will work together,” he said. “There’s a lot of humans involved. It’s not necessarily all codified. And so, [if there is] any break in the system, it’s really easy to lose trust in the entire system.”

Krikorian, who hosts the Collective’s “Technically Optimistic” podcast, was worried about 2024. Turning to Benson, he said that his research about “where people [in Michigan] are actually getting their information,” shows that it is increasingly from smaller and more obscure online platforms. Others at the summit noted that people were turning to encrypted channels like WhatsApp for political information. In other words, the propaganda pathways appear to be shifting.

“We’re actually, in some ways, spending our time maybe in the wrong places,” Krikorian said. “We need to be spending our time on these other smaller and up-and-coming platforms, that also don’t have the staff, don’t have the energy, don’t have the people and the resources needed in order to make sure that they’re secure in the process.”

Nonetheless, the remedy that Benson kept returning to was locally trusted voices. For example, her office has stationed observers within 5 miles of every voting site to investigate any problem or claim. She said that she has been engaging “faith leaders, sports leaders, business leaders, and community leaders about the truth about how to participate and how to trust our elections.”

“AI is a new technology, but the solution is an old one—it’s about developing trusted voices that people can turn to get accurate information,” Benson said. “All of this, everything we’re talking about, is about deceiving people, deceiving voters who then act on that deception.”

But rumors, misperceptions, mischaracterizations, deceptions, lies, and violence in politics are as old as America itself, as political historians like Heather Cox Richardson have noted. There is no simple or single solution, said Starbird. Nonetheless, she ended her Stanford address with a “call to action” urging everyone to redouble their efforts in 2024.

“We’re not going to solve the problem with misinformation, disinformation, manipulation… with one new label, or a new educational initiative, or a new research program,” she told trust and safety researchers. “It’s going to have to be all of the above… It’s going to be all these different things coming at it from different directions.”