Inside Mike Lindell’s “Plan” to Sound False Cyber-attack Alarms at Local Polls

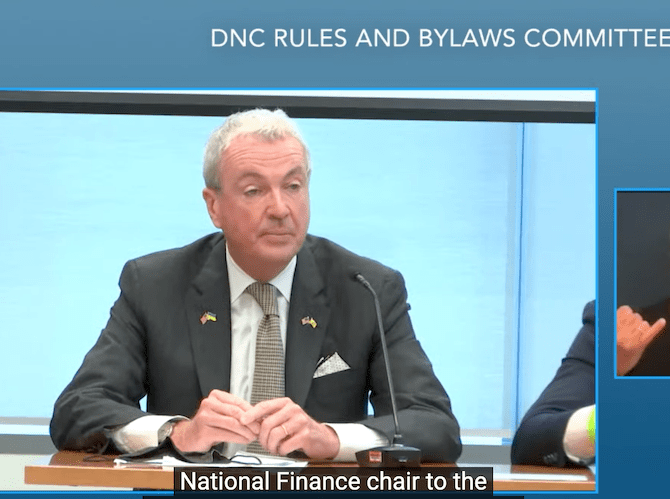

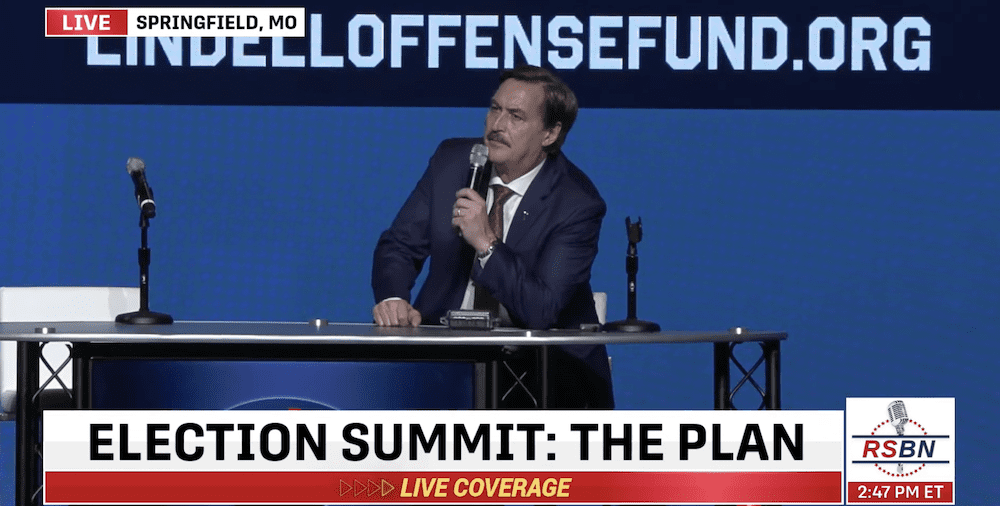

(Mike Lindell unveils his “plan” at his 2023 summit. Photo credit: YouTube.com)

(The report was published by RawStory.com on October 2, 2023.)

At his 2023 “Election Summit,” Mike Lindell, the exuberant pillow peddler turned election truther, was more manic than usual.

Lindell had assembled the most fervent election deniers from every state, mostly Trump cultists, at a conference center in Springfield, Mo., where, with great fanfare, he promised to unveil “The Plan” to prevent elections from being stolen.

Lindell’s audience was a who’s who of the election denial movement. The seats were filled with activists who had filed lawsuits challenging election results from 2020 and 2022, when the candidates they supported lost. Some had convinced a few county boards in presidential swing states such as Arizona to flout official procedures and not certify results until all of the ballots were counted by hand. There were publicity hounds, too — self-proclaimed experts on election technology, voter turnout, cyber-hacking and the hunting of suspected illegal voters. Many were right-wing media regulars who preached how Trump and his tribe were robbed, and that America’s elections cannot be trusted.

Now, in late 2023, their grievances had evolved into the realm of something that more closely resembled science fiction. Trumpian acolytes claimed that invisible hands had used the internet to sabotage computers managing voter rolls and counting votes. This narrative, and other conspiracy theories like it, were rejected in courtrooms across America by Republican and Democratic judges alike who ruled that Trump, and Trump-aligned candidates, presented no proof.

But Lindell, like other Trumpers, viewed this as a grand coverup. Even more infuriating for him: judges and journalists kept quoting election officials who insisted their counting systems were accurate and trustable – especially because they were not connected to the internet. That rationale pushed Lindell, a former crack addict who found God and became a self-made millionaire, to spend his fortune on a quest to prove otherwise.

And at his August summit, he could not keep himself from interrupting panelists to hype his plan and repeat his new war cry.

“They lied. They lied,” Lindell bellowed. “Every person lied! And every person followed that lie. Instead of wanting to look into things, they say, ‘Well, it’s not on the internet!’”

Lindell proceeded to unveil a series of electronic tools that he said would push the country to adopt a voting system that more closely resembled something out of the 19th century than the 21st: hand-marked paper ballots, in-person voting only on Election Day, all votes tallied by hand.

Lindell’s vision means ditching every computer used in conducting an election, which, literally, would revert to the late 1800s before voting machines were invented to try to prevent rigged results achieved by stuffing ballot boxes with phony paper ballots.

“I’m getting rid of these electronic voting machines to save our country,” Lindell told me in a follow-up interview. “I know exactly what I’m doing … I’m making our sales pitch easy.”

‘The plan’

Lindell’s quest is decidedly quixotic, beyond the fringe to some, particularly in light of outsized voting-fraud claims made by right-wing election vigilantes, such as True the Vote, that have consistently withered under scrutiny and failed to materialize around Election Day.

But there is a method to Lindell’s mayhem, which is both relentless and accepted as bedrock truth by a subset of Trump’s most ardent and impressionable supporters. With this comes a real danger of inciting more threats to elections officials, distrust of elections, generally, and civil strife. Come 2024, thousands of like-minded local activists may be receiving deeply misinformed messages — via Lindell’s social media network that their local polls and county election headquarters might be under an active cyber-attack.

At the Springfield conference center, Lindell, the ringmaster, instructed everyone to look at the big screen. A video camera from a drone hovered above the building. The drone approached it and flew into its lobby, and then into the large meeting room. It landed on a table on the stage where Lindell sat in front of a banner with a badge-shaped “Election Crime Bureau” logo.

The room cheered as Lindell removed and displayed its cargo. He held up a small, dark gray, electronic gadget with a blue, wallet-size screen. The gadget, he said, would prove that computers and devices used at America’s polling places and election headquarters were connected to the internet, were going online and offline, and, thus, could be invisibly manipulated from afar by their political enemies – who he frequently called the “uni-party,” meaning anti-Trump Democrats and Republicans.

“What if I told you that there was a device that had been made for the first time in history that can tell you that the machine was online?” Lindell said. “And then you could tell what the device was, where it was at, what the name of it was – ES&S 60503 – and you knew the second it went online. Well, this is what we’ve been working on for over a year. And I’m going to show you.”

He played a short video with a British-accented narrator who described what he called the “Wireless Monitoring Device.”

As the narrator told it, this WMD — not to be confused with the common acronym for “weapon of mass destruction” — was more than a box listing WiFi signals like one’s phone. It would find and identify “access points,” “routers”, “printers,” “computers,” “phones” and other devices using WiFi. It would identify their makes, models and serial numbers. It would detect online commands that engaged polling station electronics.

It would not, however, interfere with data transmission. Rather, it would send, in less than a minute, all of the detected information to a nationwide hub – the “Election Crime Bureau.” This Election Crime Bureau, in turn, would send alerts and texts via an app to activists living near the surveilled sites.

“You get the gist of the reporting, right?” Lindell said. “You’re gonna sit in your easy chair on your phone or whatever. And you’re gonna see real-time crime coming. You’re gonna know what a box [election computer] goes live. You’re going to know when a router goes live, when a polling book goes live and everything, okay… We will now become a policing of our own election.”

Lindell would not reveal where the Election Crime Bureau was located nor who would be staffing it.

The app would also address another GOP obsession. Its “Identifying and Reporting Voter Discrepancies” feature would track suspected illegal voters, he said. (Lindell later told me it would use the most current voter roll data from states and send out an alert when it detected that that six or more people with same address on their voter registration file had voted.) This feature would allow activists to investigate, he told the hall, presumably by knocking on their doors and reporting their findings to authorities.

The WMD device and voter-fraud detection app would create a true picture of why elections in America were untrustworthy, because it relied on data from the only messengers that those in Trump circles should trust – patriots like himself, Lindell said. It would enable anyone in the country using his app to see what was really happening.

“You’ll be able to find out what’s going on in other places, immediately, in real time,” he said. “You’ll be able to report that, and send it out on all your social media and everything… The way we get around the media, and the way we communicate, [is] the communication hub.”

People in the room reacted to the spyware, especially the WMD device, with glee. Those watching and chatting online via sites such as Right Side Broadcasting Network — where I saw the debut – were mixed. Some praised it. Some were skeptical.

But the WMD’s potential to incite or magnify strife around upcoming elections became instantly clear. This was a Mike Lindell-backed broadcast system that fabricated voter fraud evidence, misinterpreted facts and sounded alarms.

Among Lindell’s circle, this mattered not. They relished the prospect of a new plan to confront their critics.

“This is intended to put the fear of God into the people who stole our elections,” said Jeff O’Donnell, the WMD’s inventor, in an August 18 webcast on Telegram, a popular right-wing social media platform. “I will guarantee you RINOs [Republicans in name only] and Democrats and foreign intelligence services are talking and they’re talking about how can we still steal elections? Now the light is going to be shined on these machines that we have been promised – cross our heart and hope to die – that these machines are not on the internet.”

A reality check

Lindell spoke to me for an hour in mid-September, even though I was reporting for Raw Story, which he called “horrible, horrible news.”

I repeatedly went over “The Plan,” which had evolved since August’s summit.

I also pushed back against his baseline assertion that officials were lying when they said that no election computer was connected to the internet. I have covered election administration for two decades. I have repeatedly heard the claim of no internet connection only in regard to the machines that handled ballots and counted votes.

I told Lindell that his WMD alerts would be going off everywhere because many states use online connections for e-pollbooks — which are often i-Pads – to make sure only registered voters get a ballot. In addition, almost every voting site has printers in case a voter needs a new ballot. In other words, his system would be flagging routine polling station operations as possible cyber-attacks.

He didn’t care.

“Here’s why we did this,” Lindell told me. “This has been a year to develop these. Here’s why. All my evidence in the beginning was all cyber evidence. Okay? All cyber.”

The short comment needs unpacking.

Basically, Trump and his allied candidates have lost in court since 2020 because they could not satisfy the judiciary’s rules of evidence. So, in a sense, they today find themselves where they started – pushing conspiracy theories of “cyber” plots that somehow explain their loss by proclaiming there are hidden hands fabricating voters and tilting vote counts.

Lindell took offense when I suggested that there was other data in voting system computers that would show that almost every voter who cast a ballot was qualified. With vote counts, I said, the results could be compared to paper ballots and other data at the starting line of the tabulation process. (A year ago, I co-wrote a short e-book describing those details with Duncan Buell, a retired computer scientist and county election commissioner from South Carolina.)

Again, Lindell balked, but noted that I was citing evidence he could not see, because in some states that information was not a public record. He that complained that the voting system industry was privatized. (To be fair, those complaints also have arisen in progressive circles.)

Moving on, I asked about the WMD itself. What’s the sale price? Where can someone get one?

Lindell said the WMD, which he is manufacturing, will be road tested in three states where senior state elections officials are Republicans: Kentucky, Louisiana and Mississippi. In mid-September, he sent out a fundraising email saying, “For now, it is our goal to put at least 1,000 tools in 3 key states and targeted counties across the country for this November’s down ballot races. The cost of each of these tools in this beginning phase is $600 a piece.”

Unlike at the summit where he suggested that activists could buy the WMD, Lindell said he would start by giving these devices to county officials so that they could see for themselves if their computers were being sabotaged from afar.

“What we’re going to be doing is distributing them first to the clerks that we know out there that want to have them [the WMD] themselves, because they’re running their elections and they need to know if these machines companies lied to them — which they did,” he said.

What Lindell hopes to prove in Louisiana is unclear. The state has some of the oldest and least-reliable voting machinery in the country – entirely paperless touchscreen computers that have been considered unreliable for years. Officials cannot recover lost votes on them. They do not allow recounts. Some Mississippi counties use the same paperless machines.

Lindell said Republican election officials in these states and others were as bad as Democrats. But he said that he had a new card to play. The Republican National Committee recently passed a resolution calling for the return to hand-marked paper ballots. It also calls for minimal early voting, minimal vote-by-mail options, hand counts and the avoidance of using computers wherever possible.

“Now, the Republicans, if they push back on us, they’re gonna stand out like a sore thumb,” he said. Lindell hoped that his WMD device and app-sparked pressure by local activists would push officials to dump their election computers and embrace a machinery-free process.

That answer allowed me to raise my top concern: whether his machine might provoke violence. I asked if he was worried that his app alerts might prompt some people “to get upset and go charging down to county headquarters and start banging on doors” — which happened in 2020, and was a prelude to threats by some Trump supporters to elections officials across the country.

Again, Lindell dismissed that concern.

“No, no,” he replied. “If you remember when I had people reach out for the cast-vote records [a public records campaign in 2022], that didn’t happen, did it? I’ve got a lot of calls to action. This isn’t ‘Go march on City Hall’… I would hope people would say, ‘We want these machines gone.’”

That response is not exactly accurate, either. A recent report by VoteBeat, an online journal, profiled an Arizona election worker who was threatened and driven to end her 33-year career by some of the same people following Lindell’s call for public records.

Lindell compared this entire effort to his early strategy around inventing and selling pillows.

“I reverse-engineered any reason why you would buy this pillow and it’s the same way with these election officials,” he said. “I want to take [away] any way they could say ‘no.’ Because right now the biggest reason they’re saying no is they think the machines are secure and they are not hooked up to the internet. And they’re just using that for an excuse.”

But there is a lot that Lindell is not thinking about.

In some states, officials may not be allowed to use federally uncertified equipment at voting sites and inside county headquarters. His app that tracks allegedly illegal voters could spawn vigilante squads that violate federal civil rights laws barring voter intimidation. His WMD alarm could test new post-2020 laws that criminalize any harassment or threats to election officials. And nobody can say if an emotional and enraged partisan will be provoked by a false claim of a cyber-attack and angrily head to a poll or their county headquarters.

After all, January 6 was a “peaceful protest,” not a bloody insurrection.