Why Election Officials Are Pinning Their Hopes on Different Vote-Verifying Technologies

(Photo / Steven Rosenfeld)

In early December, the county officials running Florida’s elections unanimously endorsed a new way to recount ballots and more precisely verify votes before winners are certified.

The Florida State Association of Supervisors of Elections wanted to avoid complications seen in November’s multiple statewide recounts. They are urging their legislature to sanction a process pioneered in a half-dozen of its 67 counties. That auditing technique involves using a second independent system to rescan all of the paper ballots to double-check the initial count using powerful software that analyzes all of the ink marks. That accounting-based process also creates a library of ballots with digital images of every ballot card and vote, should manual examination of problematic ballots be needed.

Yet a few days later at a Massachusetts Institute of Technology Election Audit Summit, this emerging approach in the specialized world of making vote counting more accurate and trustable was not part of any presentation. Instead, state election directors, county officials and technicians, top academics in election science and law, technologists and activists were shown a competing approach with differing goals and procedures.

MIT’s summit mostly showcased statistically based analyses. In particular, the approach called a risk-limiting audit (RLA) predominated. Unlike Florida’s push for a process that seeks to verify every vote cast—or get as close as possible—an RLA seeks to examine a relatively small number of randomly drawn ballots to offer a 95 percent assurance that the initial tabulation is correct. It is being piloted and deployed in a half-dozen states, compared to ballot image audits in a smaller number of states and counties.

While the MIT summit’s planners could not have anticipated the Florida Supervisors of Elections’ action when planning their agenda, their embrace of RLAs—a view also being promoted by progressive advocacy groups—reflects factionalism inside the small but important world where election administrations confront new technologies. At its core, what it means to audit vote counts is being redefined in ways offering more or less precision, accompanied by tools and techniques that may—or may not—be practical in the most controversial contests, those triggering recounts.

It is not surprising that individuals who devote years to solving problems (and those who are drawn to one remedy before others) have biases. But as one of the summit’s closing speakers noted after many presentations on statistical audits and on tightening up other parts of the process, it is unwise to take any tool off the table. That advice resonates as many states are poised to buy new vote-counting systems in 2019 and 2020.

“I truly believe that the area for the fastest growth for all of us is going to be auditing,” said Matthew Masterson, Department of Homeland Security senior advisor on election security, ex-U.S. Election Assistance Commissioner and an ex-Ohio election official. A few moments later, he offered this caution to those present and watching online: “There is no one silver bullet that solves the risk management process in elections. The risks are complex and compounding. So we need to avoid, ‘If you do this one thing, you’re good to go,’ because that’s not the reality in elections.”

The MIT Audit Summit comes amid the biggest turning point in election administration since the early 2000s. Legacy vote-counting systems are being replaced by newer systems revolving around unhackable paper ballots. Meanwhile, advances in counting hardware and software, diagnostic analytics and audit protocols present new ways for verifying vote counts. That’s the promise and the opportunity. The reality check is that election administrators must weigh the costs, efficiencies, complexities and compromises that accompany the acquisition and integration of any new system or process.

This juncture poses large questions for the world of election geeks, as those at the MIT summit proudly call themselves. Is technology changing the way that officials and the public should think about, participate in, and evaluate reported outcomes? Can a new tapestry of tools and procedures yield more transparent and trustable results? Are new developments better suited for verifying the votes in some races but not others?

These concerns are not abstract. The political sphere is beset by “post-truth” realities, where facts are often subordinated to partisan feelings. Yet federal courts routinely issue rulings citing the citizenry’s expectation of one-person, one-vote, including constitutional guarantees of equal protection in elections. These clashing factors and expectations put additional pressures on election administrators to earn the public’s confidence.

In the world of administering elections, the options and decisions surrounding the choice of voting systems and related procedures quickly become concrete, including strengths and weaknesses of any tool or practice. As Ohio State University election law professor Edward (Ned) Foley said in the summit’s closing panel, the debate over how accurate vote counting should be is as old as the United States.

“This is a theme that goes all the way back through the beginnings of American history,” Foley said. “This debate was between Alexander Hamilton and James Madison. When they had their disputed elections way back in the beginning, Madison’s view was, ‘We’ve got to get the correct answer in this election right. We cannot tolerate an error in the vote-counting process in this particular election.’ Hamilton said, ‘No, no, no. That’s too difficult a standard. At some point, you have to stop the counting process and say we’ve got to have a winner. And you know what, there’s going to be another election…’”

Looking at an audience, Foley asked, “What’s our standard of optimality, because we are never going to have perfection?”

Center Stage: RLAs

Those presenting at MIT’s Audit Summit showed that many steps in the overall voting process could be tightened by statistical or other data-based audits, just as they cited pros and cons of the various statistical audit techniques presented. The summit gave a clear impression that this field was rapidly evolving.

The conference featured ways to streamline random ballot selection before applying the statistical math: foot-high piles of ballot cards are loosely shuffled, as one would do with sections from a deck of cards, with top cards pulled before starting the counting analysis. It discussed how voter registration data could correctly (or not) parse voters into districts and precincts. But organizers were primarily focused on showing what a risk-limiting audit was (or one version) and touting Colorado’s experience pioneering it.

Risk-limiting audits were developed by Philip Stark, an acclaimed mathematician and chair of the Statistics Department at the University of California in Berkeley. The genesis goes back a dozen years, when many states were buying the voting systems now being replaced. Stark and others realized there were not very accurate ways to re-check vote tabulations. Under that umbrella are two terms and tasks that often get confused and sometimes overlap: audits and recounts.

Audits, generally speaking, seek to evaluate specific parts of a larger process. The basic idea is using independent means to assess an underlying operation or record. In elections, some states audit vote count machinery before winners are certified. But other states do it afterward. Recounts, in contrast, are a separate final tally before the winners are certified, and often operate under different state rules (as seen in Florida this November). In some cases, these two activities overlap: pre-certification audits can set a stage for recounts.

For many years, vote count audits meant taking a second look at ballots that were a small percentage of the overall total and seeing if those votes matched the machinery’s count. In many states and counties, that meant looking at one race, and often grabbing ballots from a few precincts that met the sample size. That analysis didn’t reveal much about countywide or statewide counts. Stark and others sought a better way to check counts.

Their solution is a form of statistical analysis called a risk-limiting audit. This process requires all of the voted ballots be assembled in a central location. Depending on the threshold of assurance sought (typically 95 percent), ballots are randomly drawn and manually examined to see if the individual ballots match the overall initial tabulation. Participants tally the observed votes. The math here is based on probability. In races where the winning margins are wide, the volume of ballots to be pulled and noted to reach that 95 percent assurance can be small. That is RLA’s selling point: it can be expeditious, inexpensive and offers more certainty than prior auditing protocols.

But when election outcomes are tighter, including those races triggering state-required recounts, the inverse becomes true. Much larger volumes of ballots must be pulled and examined to satisfy the 95 percent threshold. How many ballots varies with the number of votes cast in the entire contest, the margins between top contenders and the chance element of random draws. At some point, an RLA’s efficiencies break down because the manual examination turns into a large hand count of paper ballots (as seen in the final stage in Florida’s recent simultaneous statewide recounts).

This spectrum of pros and cons was seen in the RLA demo led by Stark at MIT.

Rolling the Dice to Verify Votes

After several panel discussions and testimonials, the audience simulated one version of a risk-limiting audit. What emerged was a scene akin to a science fair. People stood in groups around tables. They rolled dice to generate random numbers. They substituted decks of cards for ballots—with red and black cards standing in for candidates. They followed Stark’s printed instructions to evaluate two hypothetical contests.

Using a combined deck of 65 cards (52 black, 13 red) for the first audit, the task was seeking a 90 percent assurance the results were correct. The cards were separated into six piles. The cards were counted to ensure they added up to 65. Each group made a “ballot look-up table” to randomly select cards from the batches. Dice were rolled to generate random numbers. Then, as cards were pulled from the piles, a score was kept—awarding varying points depending on whether the card was red (subtract 9.75) or black (add 5). Once the score got to 24.5—according to the underlying math—the audit was done.

“Audit!” Stark’s instructions ended. “The number of ballots you will have to inspect to conform the outcome is random. It could be as few as 5. On average you will need to inspect 14 ballots to confirm the contest results.”

Most of the participants could follow these instructions—although some groups finished after pulling fewer cards than others. In the second exercise, using 50 red and 50 black cards to simulate a tie, the 90 percent confidence threshold also was applied. Cards were sorted, randomly pulled and notes taken. But because this intentionally was a tie, the process was more laborious. Stark’s instructions anticipated that consternation, noting this audit, were it real votes, would become another process—a full manual count:

“Continue to select cards and update the running total until you convince yourself that the sum is unlikely ever to get to 24.5 (generally, the running total will tend to get smaller, not bigger). When you get bored, ‘cut to the chase’ and do a full hand count to figure out the correct election outcome. Because this risk limit is 10 percent, there is a 10 percent chance that the audit will stop before there is a full hand count, confirming an incorrect outcome.”

If this process seems complex, it was. Not everyone in a room filled with election insiders (including some of the nation’s top election law and political science scholars) could follow the instructions. A few big names were publicly teased. One participant later suggested that the process might have been easier had a walk-through first been shown on the auditorium’s screen.

Nonetheless, those endorsing RLAs said there were great benefits to be gained by doing them, saying, once learned, they brought a heightened diligence to the ballot custody and vote-counting process. They urged those observing RLAs for the first time to be patient and suspend judgment.

Many Questions Were Raised

In the follow-up discussion, Karen McKim, a Wisconsin election integrity activist, recounted how she had used Stark’s instructions, found online, to conduct RLAs with county clerks in 2014 and 2016. But she used digital images of the ballot cards (made by optical scanners) instead of randomly pulling the paper. McKim said she liked the speed and visual impact of using images, but said the number of ballots to be examined was so small that some voters did not have “emotional confidence” about the process. She asked Stark whether it would hurt to keep pulling ballots until skeptics were satisfied.

It would not, Stark replied, saying RLAs were a minimal standard for how much auditing to do, amid their wider benefits.

Walter Mebane, a University of Michigan political scientist, Washington Post columnist and “election forensics” expert, told Stark that he required his advanced students to read Stark’s papers on RLAs. But picking up on McKim’s concern about giving the public “emotional confidence” about verifying votes, Mebane said RLAs rely on “voices of authority”—amounting to every statistician saying they would do the same thing.

“This is fine when this is not [an] important” election, Mebane said. “But we are in an era now when expertise is no guarantee of anything. If you’re important, then our president, for example, is happy to denounce expertise, and I can guarantee you there will be experts on either side with their presumably bogus arguments. But what is the way to explain this? I get frustrated. I say we have to explain to people what statistics is in some fundamental sense… I don’t think arguments from authority can survive a sustained form of [propagandistic] attack.”

Stark replied the math behind RLAs was available and as such was “transparent,” even if one needed “to learn two years of math to do it.” He then offered an analogy, saying that pulling random ballots was like tasting a sip of well-stirred soup. “If you stir it well, and take a tablespoon, that’s enough. If you don’t stir it, all bets are off. It’s the stirring and then taking a tablespoon that amounts to a random sample… I don’t expect everyone to be able to check the theorem. I do expect everyone to be able to check the calculations based on the theorem… An astute fourth-grader could do the arithmetic.”

After other questions, Stark returned to McKim’s comment and made a crucial point to RLA’s promoters. He emphasized that vote count audits were not the same as recounts, which would be a new counting procedure that would have to resolve the closest contests.

“The decision whether to do a recount is different from the decision whether to audit more; you need to decouple those,” Stark said. “The other thing I have to interject is I don’t view auditing from [digital ballot] images as a risk-limiting audit, for reasons I think everyone here understands. Because it’s not the artifact that the voter looked at; there are lots of things that can cause there to be a different number of images.”

Looking Beyond Factions

This exchange, while deep in the details of vote verification techniques, revealed key decision points facing election officials and schisms among experts about solutions. The MIT summit showed there are new ways to verify the accuracy of vote counts as many states are poised to buy new gear that likely will be used for years. Indeed, the push by Florida Supervisors of Elections to use a second ballot image-based system to audit their initial tabulations is additional evidence of this overall vote-verification trend.

But what was glossed over at MIT’s summit was the fact that not every audit technique could handle all of the stages in progressively verifying vote counts. RLAs, despite their complexities, can be efficient in affirming outcomes in races that are not close—as Mebane put it, “not important.” As the margins tighten, those efficiencies vanish.

That turnaround raises big questions, considering RLAs’ backers have been successful in getting some state legislatures to require them before certifying election outcomes. What are those states going to do when the public sees election officials start an RLA, but have to shift to another start-to-finish process to recount? What happens when this vaunted verification process can’t take closest races across the finish line?

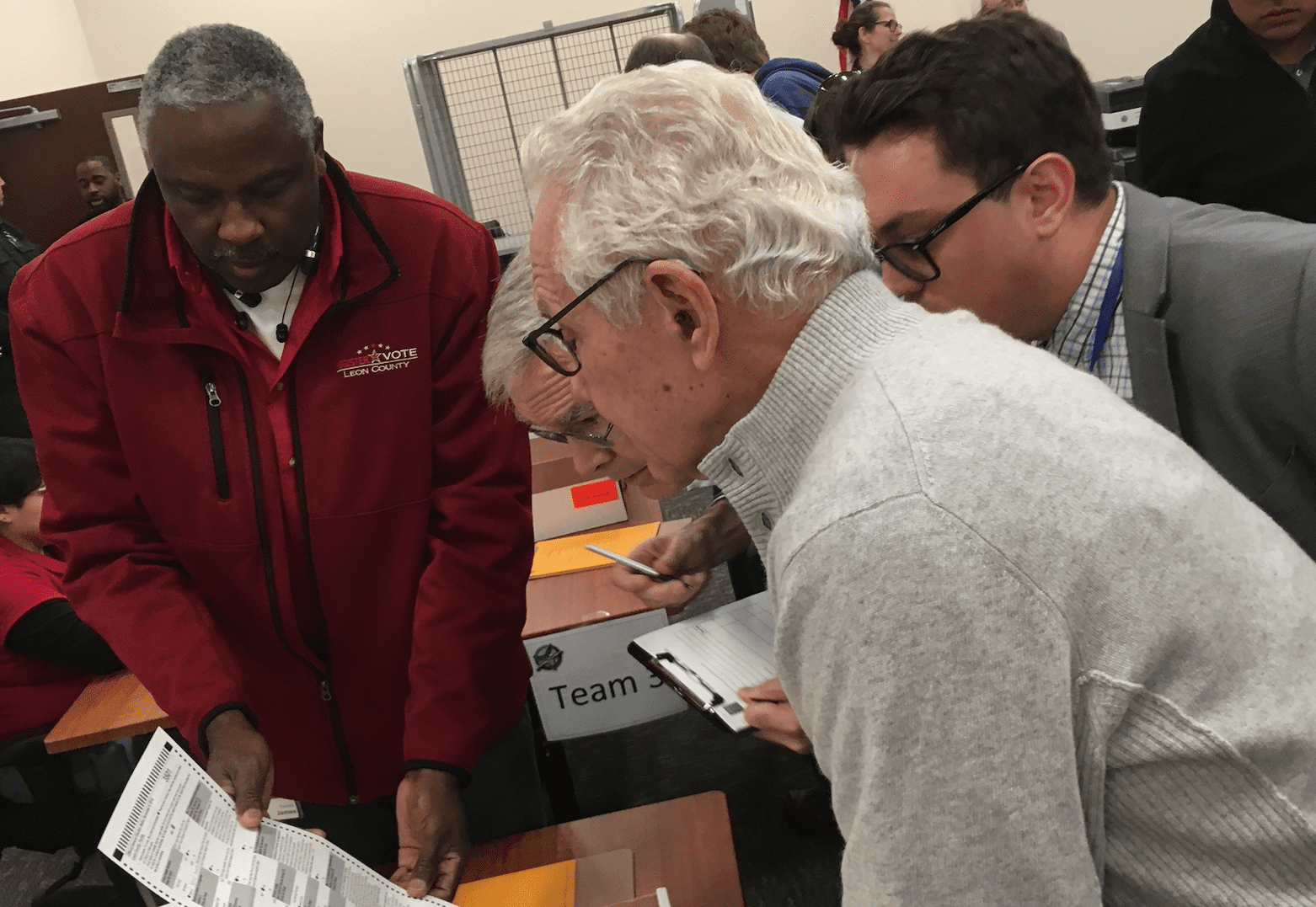

That is not conjecture. Similar dynamics were just seen in Florida’s three simultaneous statewide recounts. There was not a smooth transition between the way ballots initially were handled and initially tabulated and subsequent two-stage recount. Some counties that had carefully indexed their ballots saw those libraries turned into veritable haystacks as they followed Florida’s current process: a coarser sorting and counting, followed by manually examining tens of thousands of certain categories of questionable ballots.

Some of Florida’s biggest counties could not finish the recounts due to their machinery, protocols and state deadlines. That was partly why its election supervisors, meeting a few days before the MIT summit, endorsed a resolution urging their legislature to allow them to use a second independent ballot-scanning system with visually oriented software for future recounts. That news was not mentioned at MIT.

There are explanations why not—namely many mathematicians, cryptographers and election integrity activists distrust anything involving computer records and analytics. But there’s a bigger point beyond parsing their beliefs. Every auditing approach has strengths and weaknesses. The verification choices—RLAs, other statistical audits, image audits, hand counts—differ in what stages of the process and scale they can handle well. Their goals, estimating an election’s accuracy or a fuller accounting, also vary.

Put bluntly, MIT’s chosen tool—risk-limiting audits—cannot expeditiously cross the finish line in photo-finish elections or in recounts in high-population jurisdictions.

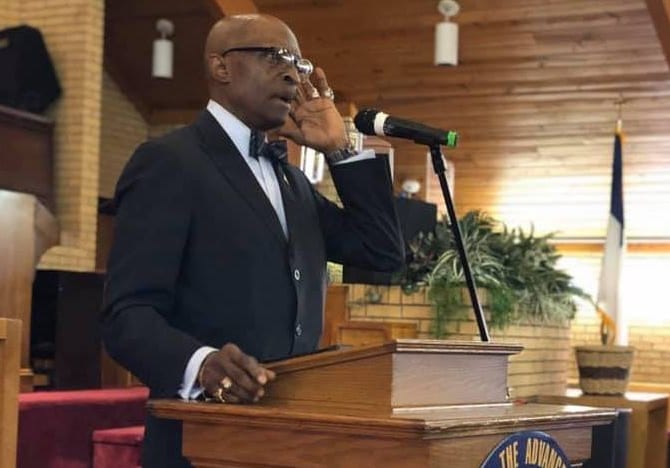

“It is a solution that is not practicable, particularly for the large practitioner,” said Ion Sancho, who recently retired as the Supervisor of Elections in Leon County, Florida, after nearly three decades in that job, and who helped develop the ballot-image audit system just endorsed by his former peers. “It [an RLA] is scientifically valid, what they are doing. But it doesn’t lend itself to the kind of organized, pre-planned activity that matches everything else we’re doing. Everything has to be pre-planned. The process has to be as efficient as possible… How do you plan [an RLA] for what happened in Florida with three races within one-half of 1 percent, and two within one-quarter of 1 percent?”

These pros and cons do not mean that this array of new audit tools should not be used. These technologies and techniques should be deployed—but deployed knowingly and judiciously. They should be targeted to the task at hand—not oversold. They should be assessed to see how they could be integrated into a more streamlined ballot inventory, vote-verifying and confidence-building process.

For example, RLAs require that all of the ballots in a race to be audited be assembled in one location. In Colorado, which votes entirely by mail, that’s more easily done than in states using precincts, mail and vote centers. Once assembled, the numbers of ballots in storage boxes must be checked before an RLA can start pulling random ballots to physically examine and start its math. Contrast that process and ballot inventory with what Florida officials seek to do: a second scan (no data from the initial tabulation is used—only the actual ballots) to create a new tally and searchable library of every vote, and where the ballots are scanned in batches tied to the first scanners used (to trace machine errors).

“Here’s the difference as a practitioner of elections: good enough is not good enough for me,” said Sancho. “I’ve dealt with this issue for such a long time. It’s one of the reasons I pulled back from the Electronic Verification Network [including RLA co-authors]. I really like those individuals… but I want to know what I can do to train out of my citizenry the typical mistakes they are making, which may make their ballot or their vote not count, or slow down the process, or reduce the overall efficiency.”

Stepping back, this spectrum of emerging audit tools and a push for verifying votes is a positive development. It is a counterpoint to post-truth rhetoric shadowing political campaigns. But the factions inside the insular world of verifying votes should heed Matt Masterson’s cautionary note—there is no one-size-fits-all solution. They should ponder Ned Foley’s historic frame: how accurate do Americans expect their vote counts to be? And officials buying new voting systems should ask themselves if they will be able to withstand the propagandistic attacks that Walter Mebane said will be forthcoming.

Why can’t paper ballot libraries be built that support RLAs and ballot image audits before certifying outcomes? Why can’t random ballot selection techniques affirm that digital ballot images are correct? Why can’t hand counts—which are less accurate than scans, according to new research based on the Green Party’s 2016 presidential recount—be selectively used after mountains of paper are turned into libraries? Why can’t problematic ballots quickly be identified and pulled for scrutiny as the public watches online?

As Ned Foley said, how accurate do Americans want their vote counting to be?

Also Available on: www.alternet.org