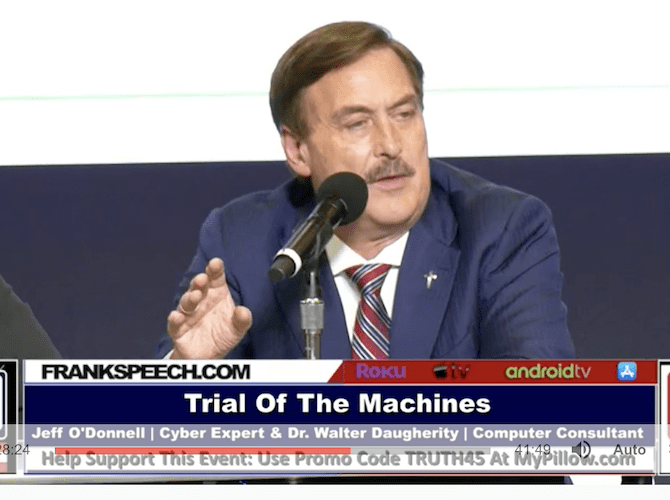

With 1,000 Complaints of Election Theft, Garland has Gotten One Conviction

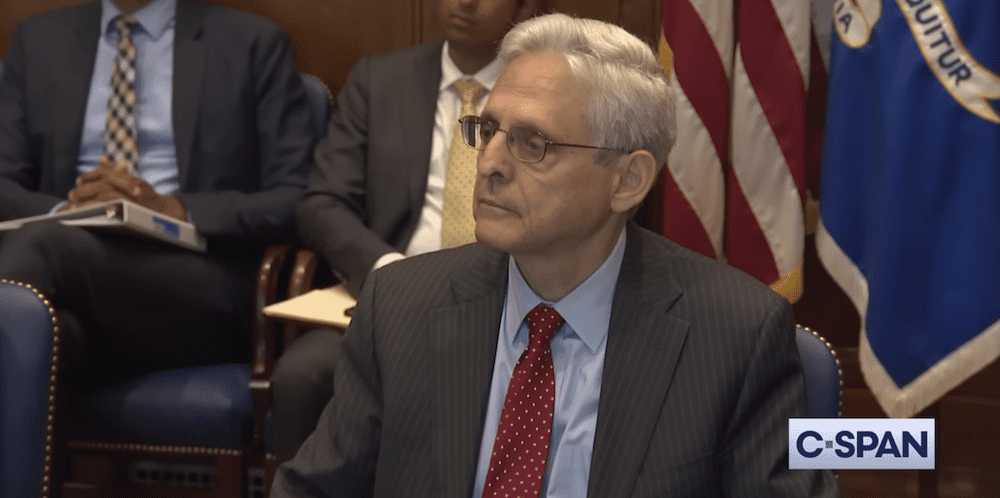

(Attorney General Merrick Garland. Image: www.youtube.com/watch?v=sY5x0wpGzi4.)

A Department of Justice task force to combat violent threats against election workers has received more than 1,000 referrals since it was launched in July 2021 but has only secured one conviction, a House hearing revealed Wednesday.

“It’s received well over 1,000 reports of threats, but it’s only secured one conviction,” said Rep. Richie Torres, D-NY, House Homeland Security Committee vice chair. “Which raises the question, ‘Why only one conviction?”

At the hearing on the election security landscape, the lack of accountability was also tied to more local law enforcement. Often police departments were reluctant to press charges after being contacted by the election officials, the committee was told, because police officers often did not know where the legal line was between illegal threatening conduct and permissible political speech.

“Law enforcement, in many cases, is unaware that issues on Election Day or leading up to the election can be a real threat or a real issue,” said Neal Kelly, who now chairs the Committee for Safe and Secure Elections, which seeks to educate police on this issue, and was formerly the registrar of voters in Orange County, California, and was a police officer before that.

“Beat officers, officers on the ground, just are not familiar with criminal code for election violations or that threats to election officials are occurring in large numbers,” he said. “When I was in Orange County, I had police officers respond to some scenes and they just thought it was a civil matter. They were not aware that there were actually criminal violations that occurred at a vote center.”

The House hearing comes as 2022’s general election is heating up and there is disagreement over what are the biggest ongoing threats facing voters, election officials and American democracy. Polls conducted since the House January 6 Committee has been holding hearings detailing ex-President Donald Trump’s attempts to overturn the 2020 election have shown many voters, especially independents, want provocateurs and insurrectionists held accountable.

“The threats to election security vary widely in the United States,” said Torres. “There’s the threat of a cyberattack on election infrastructure. There’s the threat of influence operations that radicalized people with misinformation and disinformation… And there’s a threat of violence and harassment and intimidation against election officials themselves.”

Torres asked which threat was mostly likely to “endanger” the 2022 midterms.

Elizabeth Howard, a senior counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice and New York University law school and a former Virginia state election official, replied that widespread threats to election officials were her top concern “because of the cascading effects that result.”

“What we’re seeing across the country are election officials who are deciding to leave the profession,” she said. “For example, five of Arizona’s 15 counties now have new election directors this cycle. Six of Georgia’s most populous counties have new election directors this cycle. This creates the potential for more mis- and disinformation because the people taking the retiring election officials’ place are not going to have the same level of experience [running elections].”

Kelly said that the 2020 election “amplified” the harassment, but “I’ve heard them before. If you go back to 2018 in Orange County, there was a number of similar threats and issues arose when we had congressional districts flip from red to blue… It’s not just at the national level. It can certainly happen at the local level. We see that, and I will say this, it’s not just the battleground states.”

“In every single election we see rumors, we see myths and disinformation,” said New Mexico Secretary of State Maggie Toulouse Oliver, a Democrat, who had to leave her home and have police protection after the 2020 election and after her state’s recent 2022 primary. “Those rumors tend to peter out.”

“Unfortunately, we are still on a daily basis, in my state and across the country, living with the reverberating effects of the big lie from 2020,” she continued. “The recent activities that happened in my state where we almost failed to certify an entire county’s worth of votes in a primary election [Otero County] are a direct result of that rhetoric.”

At Wednesday’s hearing, Democratic congresspeople were united in squarely blaming Trump’s false stolen election claims, and, to a lesser degree, social media platforms, that paired conspiracy-minded people with conspiracy theorists, for the uptick in threatened violence. Republican committee members, in contrast, said increased federal oversight of state-run elections was their top worry, and often went on to repeat Trumpian conspiracy theories about 2020.

“Isn’t it true, by implication, that the ballots cast in Wisconsin – by absentee drop box deposited ballots – were illegal in the 2020 election,” Rep. Dan Bishop, R-NC, asked Oliver, referring to July 2022 ruling by the Wisconsin Supreme Court that banned their use one month before the state’s upcoming primary.

“I cannot speak to the ins and outs of the specific legality, the constitutional questions that came forth in Wisconsin,” Oliver replied. “What I can tell you is that in states like mine, where we have secure 24-hour monitored systems that are permissible under state law, [that] we do not see the level of concern. And frankly, the alleged fraud that has been leveled against such ballot collection systems.”

These kinds of exchanges evaded the central question of what the most pressing security threat was facing upcoming midterm elections. And, as important, what could be done to counter election-centered threats and violence?

“When something like 40 percent of Americans believe that the 2020 election was stolen, about 60 to 70 percent of Republicans… clearly, that is the root cause of the threats of violence that many nonpartisan election officials are facing,” said Rep. Tom. Malinowski, D-NJ, addressing Ohio Secretary of State Frank LaRose, a Republican, where polls have found 62 percent of Republicans still believe the 2020 election was stolen. “What should responsible leaders in our country be doing to address that false believe out there?”

“I guess I find the silver lining to every cloud – that folks are interested in this topic right now at a level that they would not normally be,” replied LaRose. “I view this as an opportunity to educate people about the safeguards that exist, and make sure that information is available in every part of our state.”

Only the committee vice chair, Torres, asked repeated questions about the Justice Department’s election threats task force and why it only had one conviction.

“Is the issue one of law and the law is insufficiently protective of election workers or is it one of enforcement?” he asked. “What’s going on?”

“The DOJ task force has taken important steps but clearly what they’ve done is not enough,” Howard replied, summarizing her more detailed written testimony. “We think that they need to expand the task force to include state and local law enforcement. As our Brennan Center survey showed, almost nine out of 10 election officials who had been threatened reported those threats not to federal officials, but to their local law enforcement.”

The DOJ did not testify. But later in the hearing, Kelly amplified Howard’s comments by noting that most local police officers are unfamiliar with election-related crimes and are reluctant to present cases to local prosecutors.

Meanwhile, elsewhere in Washington, Attorney General Merrick Garland spoke to reporters and pushed back on the accusation that the DOJ wasn’t doing enough to hold perpetrators of 2020-related election violence accountable.

Garland replied:

“There is a lot of speculation about what the Justice Department is doing, what it’s not doing, what our theories are, what are theories aren’t, and there will continue to be that speculation. That’s because a central tenant of the way in which the Justice Department investigates — a central tenant of the rule of law — is that we do not do our investigations in public. This is the most wide-ranging investigation and the most important investigation that the Justice Department has ever entered into. And we have done so because this represents, this effort to upend a legitimate election, transferring power from one administration to another, cuts at the fundamental of American democracy. We have to get this right. And for people who are concerned, as I think every American should be about protecting democracy, we have to do two things. We have to hold accountable every person who is criminally responsible for trying to overturn a legitimate election. And we must do it in a way filled with integrity and professionalism – the way the Justice Department conducts investigations. Both of these are necessary in order to achieve justice and to protect our democracy.”

Garland primarily was referring to crimes surrounding the planning and execution of the insurrection at the Capitol on January 6, 2021. (Other recent news reports have said that internal DOJ memos suggest the department would not likely indict Trump before the 2022 midterm elections, if he were to be indicted.)

In contrast, the testimony before the House Homeland Security Committee concerned the ongoing and current threats to local and state election officials by followers of the big lie, where local and federal police, for differing reasons, have barely held those threatening violence to account.