Are Iowa’s Days as the Nation’s First Presidential Nominating Contest Numbered?

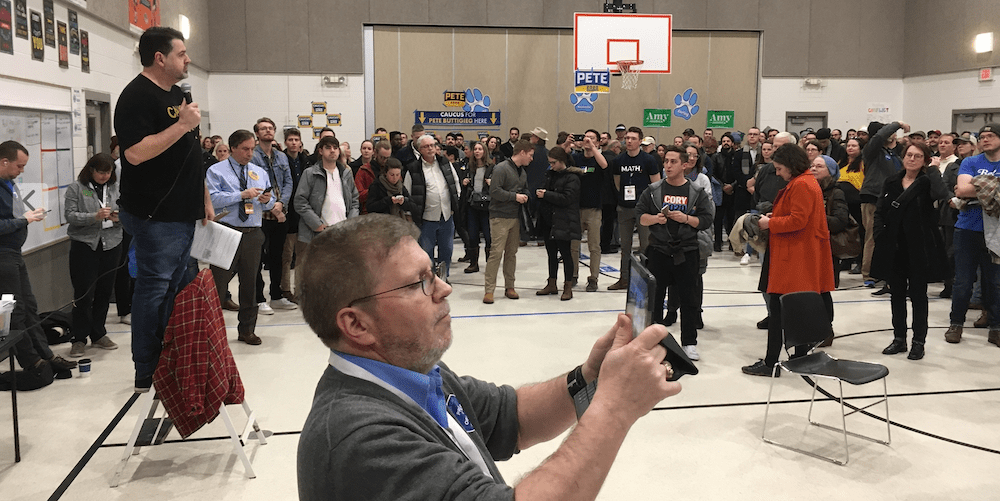

(2020 Iowa Democratic Party caucus. Photo by Steven Rosenfeld)

In the past half-century since the Iowa caucuses have led off the presidential nominating season, only one Democratic candidate who was not already president—a U.S. senator from the neighboring state of Illinois, Barack Obama—went on to win the White House. Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, and Joe Biden all lost in Iowa in their first bid for the presidency, even though they went on to win the nomination and the election.

The record for Democratic presidential candidates in New Hampshire, the nation’s first presidential primary election, isn’t much better. In the same time period, only Carter—in his first campaign for the presidency in 1976—won the state’s primary, Democratic nomination, and White House.

These awkward facts, coupled with criticism that both states’ voters do not reflect a sufficiently diverse cross-section of the national electorate, and a technical meltdown during Iowa’s 2020 caucuses that led to its results being delayed, have led the Democratic National Committee to open its first review since 2005 to reassess which states will open the 2024 presidential nominating season.

“Our party is best when we reflect the people we are trying to serve,” DNC Chair Jaime Harrison told the DNC’s Rules and Bylaws Committee (RBC) on March 28. “I want folks to understand that this process, like all of the processes that we have gone through time and time again after each election cycle, will be open. It will be accessible. And it will incorporate the diverse perspectives that make our party strong.”

Harrison’s language, like much of the RBC meeting, was cordial, and emphasized transparency and inclusiveness. But it was clear, from the comments made by several RBC members, that Iowa’s days as the nation’s first contest, a party-run caucus, may be numbered. If the state kept an early role, it would be conducted as a party-run primary—not a party-run caucus—which, in itself, would be a major change inside the state and nationally.

More pointedly, the jockeying has begun over which mix of states might take part in a series of coordinated opening primaries on the same day in different regions of the country. While it is impossible to predict what will emerge from the RBC’s review, which it hopes to present this August, voices have suggested that Michigan, New Jersey or Wisconsin should replace Iowa, amid concurrent elections in Nevada, New Hampshire and South Carolina.

“As things stand right now, the first state to hold a delegate selection process in 2024 would be Iowa, whose 80 percent white electorate hasn’t voted for a Democratic presidential candidate in a decade,” wrote Morley Winograd, a former RBC chair and top party official who oversaw the creation of the party’s opening primary schedule, in a March 25 blog at the Washington-based Brookings Institution. “The second state would be New Hampshire, which may have more of a historical and legal claim [since 1920] to be ‘first in the nation’ but whose electorate is even whiter, 90 percent, than Iowa’s… Most importantly, neither state voted for Joe Biden’s candidacy in 2020.”

Morley was welcomed at the March 28 meeting by James Roosevelt Jr., RBC co-chair, who said that the panel looked forward to hearing from him. At the meeting, Harrison announced that the RBC would be holding “three national virtual listening sessions” in coming months to gather input from the public and stakeholders. RBC members also suggested that state parties, unions, political scientists, and past and future presidential candidates should all weigh in.

But the groundwork was already being laid for reconfiguring what the RBC committee refers to as “the pre-window period,” which are the nominating contests before the numerous primaries held on the first Tuesday in March, called Super Tuesday, and the final contests in mid-June.

As Roosevelt summarized, the RBC is envisioning a process where state parties would apply and make their case for an early slot. The panel is looking at several criteria, which are priorities but not inflexible. States should commit to a primary election, not a caucus. States should also play a competitive role in the fall’s general election. And they should have a diverse electorate.

New Priorities, Led by Diversity

At the meeting, some RBC members began to press various constituencies’ cases, starting with a push for choosing early states that have a more racially diverse electorate.

“We know that we can engage more diverse groups that we need to help us win in the general election,” said Donna Brazile, a former DNC chair, presidential campaign manager and recent Fox News analyst. “It’s time for us, Mr. Chairman, to take a hard look at this.”

“We cannot be stuck in a 50-year-old calendar when we are trying to win 2022 and 2024,” said Leah Daughtry of New York. “This idea of considering the changing electorate is so important. Our country is very different than it was when we first set up the [pre-Super Tuesday] window… African Americans comprise 25 percent of rural America, and when you add [in] Latino Americans and Native Americans, rural America is nearly 40 percent people of color.”

But other members countered that the presidential campaigns prefer smaller states.

“[What] presidential candidates have always wanted from us… is that the early states be small states, and I do not see that listed in this framework,” said Carol Fowler of South Carolina. “And presidential campaigns have very good reasons for that. It has to do with cost. It has to do with a candidate who is not well known being given a benefit about campaigning in small states before they move onto larger states. I do hope that will be something that we can consider.”

“Carol’s right,” said Scott Brennan of Iowa, speaking several minutes later. “I think it would be very helpful to hear from presidential campaigns, folks like that, because, again, well, I think the touchstone is electing Democratic presidents.”

David McDonald of Washington noted that the RBC had yet to formally specify how it would assess states. Like Fowler and Brennan, he said small states help “startup” candidates.

“The states that are upfront are basically smaller states, more accessible to startup candidates; they’re not major media markets,” McDonald said. “I would hope that we will continue to have the upfront window be as accessible as possible to candidates and not slide into a situation where, essentially, we end up with four large states upfront and an election decided based on mass media markets.”

Even though the RBC’s review has barely begun, there is also lobbying by politicos in states seeking to preserve their early role—as well as the prestige and millions of dollars in political campaign dollars spent by candidates, new media, and constituency groups.

Early Reactions

Art Cullen, editor of the Storm Lake Times in northwest Iowa, recently wrote a Washington Post opinion piece where he said the DNC was poised to bypass and disrespect rural America, and, with that, extinguish the prospect of another candidate like Obama emerging and triumphing.

“Yes, the Democratic National Committee is holding its quadrennial ritual of lashing us deplorables because, its notables believe, the two early-voting states do not represent the electorate and because politicians hate having discerning voters run the show,” he said.

“The caucuses are misunderstood—they were never meant to pick a winner,” he continued. “Their role is to winnow the field—down from 10 or 20 candidates sometimes to five or six viable campaigns going into New Hampshire. In 2020, the Democratic winner was picked by Black women turning out in droves for Joe Biden in South Carolina.”

But even South Carolina, despite Biden’s debt to that state’s Democrats, might not make the RBC’s final cut, as it hasn’t elected a Democratic presidential candidate in the fall since Jimmy Carter in 1976 and is not a battleground state. (The DNC, however, historically follows an incumbent president’s preferences.)

Nevada, despite its diversity, has other problems. The state party has internal leadership fissures after Democratic Socialists swept all the positions, prompting Nevada’s top elected Democrats to create a “shadow party.” In 2020, the state party ignored the RBC and used untested software to tally its caucus votes, causing delays in announcing the winner that were longer than Iowa’s breakdown weeks before. (Because Bernie Sanders won by a large margin, the press ignored the technical snafus.) In 2021, Nevada passed legislation making it the earliest presidential primary state in the West.

In contrast, Iowa, which has become an increasingly red-run state in recent years, has not passed legislation to replace its caucuses with a government-run primary. That means Iowa’s Democratic Party would have to stand up another entirely new voting system in 2024—if it preserved its early role—after the high-profile failure of its new voting system in 2020.

And Winograd, who led the RBC decades ago and had a major role in shaping the party’s current schedule, apart from pushing for Michigan to replace Iowa (he was that state’s Democratic Party chair in the 1970s) also noted in his recent blog post that New Hampshire might have to change its primary rules to satisfy the committee’s new requirements.

“There is, however, one thing New Hampshire can do to assure their first in the nation status, at least for 2024,” he wrote. “To deal with the state’s lack of diversity, the party should permit only registered Democrats to vote in its primary in 2024, abandoning their tradition of allowing voters from one party to vote in the other party’s contest.”

The RBC is heading into stormy waters. The politics, voting rules, and election administration details quickly become complicated. For example, other states, such as South Carolina and Virginia, have open primaries where voters who are not registered Democrats can participate. The RBC is unlikely to pursue a rule change that would upend more states than necessary.

No matter what the RBC decides, some states will not be pleased, which raises another possibility. The earliest nominating races, while high profile, only involve a small number of the delegates needed to win the nomination. Thus, small states might ignore the DNC and proceed no matter what, even if the RBC sanctions them after the fact—as it did in 2008 when Florida and Michigan moved their primary dates. (The RBC stripped both states of half of their delegates, but restored them before the national convention.)

Meanwhile, the competition to be first only promises to become more heated.

“Why not end the early primaries with the most bitterly contested swing state in the nation—Wisconsin?” wrote the New Republic’s Walter Shapiro, a veteran political journalist who first covered the Iowa caucuses in 1980, endorsing yet another Midwestern state.

“What matters more than anything is that the Democrats retain for 2024 and beyond the most democratic aspect of running for president,” he wrote. “And that is creating a system under which candidates do not view most of America as flyover country as they race from major media market to major media market. Even in a nation of 330 million, personal campaigning should matter.”