AI Can Make You Believe Russian Propaganda

(Image: https://cyber.fsi.stanford.edu)

(The report was published by WashingtonMonthly.org on June 6, 2023.)

Before Alex Stamos became director of Stanford University’s Internet Observatory, he was best known as a renowned cybersecurity expert. He famously left his post as Facebook’s chief security officer after the company would not reveal the extent to which Russian trolls created and paid for inflammatory ads that meddled in America’s 2016 presidential election.

Now he has turned his attention to artificial intelligence, or AI. After the 2020 election, Stamos and Stanford researchers tested how effectively foreign countries could target Americans using AI language-generating tools.

In mid-April, Stamos and Stanford’s Shelby Grossman led a webinar where they previewed a forthcoming paper, “Can AI Write Persuasive Propaganda?” Their answer was a firm “yes.” AI was almost as persuasive as real Russian and Iranian propaganda used in recent years to distract, divide, and deceive Americans.

The capacity of publicly available AI to mass-produce and deliver misleading messages and news-like articles will make 2016 seem like child’s play.

“From my perspective, I think we’re entering an incredible era of bullshit,” Stamos said. “The marginal cost has gone effectively to zero for content creation. That was not true before. And as bad as everything is on the Internet [today], I think we are entering an incredible era of things that you can’t trust.”

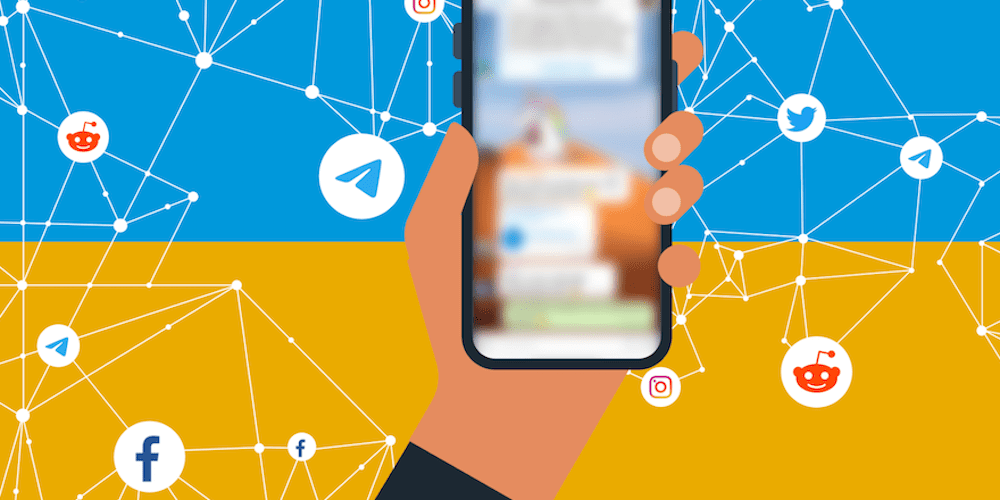

Dishonest humans are already able to script claims that get bad scores from fact-checkers and create social media personas and accounts to spread misinformation, via ads, texts, tweets, hashtags, comments, and e-mail. But the Stanford study previews a far more disturbing future: authoritarians using AI to fabricate massive amounts of believable and manipulative longer-form content that looks no different than the news on a smartphone. We could be facing a world where it is very hard to figure out what is or is not true.

Asked if there are tools that can detect AI-produced propaganda, Grossman said, “It’s very difficult to do this. If an unsophisticated actor like a high school student is using this to plagiarize or is using this to write an essay, I think it is easier to detect. But I think if sophisticated actors are doing this, at the moment, there’s no good way to detect it.”

The Stanford research is part of a growing body of academic work that has found that today’s publicly available language-generating AI tools can create believable content. Other recent research has found that thousands of state legislators across the U.S. believed AI-generated emails were written by constituents. Another study found that Idaho regulators believed AI-generated “public comments” that were submitted for its new Medicaid rules.

The Stanford study differs from those two prior experiments because it focuses on longer-form content, disguised as news-like articles, in which lies are added to threads of real events. Such content, consisting of sentences and paragraphs, is harder for AI to produce than texts, tweets, or forged photos.

The Stanford researchers wanted to see if GPT-3, a language-generating program created by San Francisco-based OpenAI.com, could write summaries and short news articles that would be as persuasive as real foreign propaganda aimed at Americans. GPT-3 is one of a dozen language-creating tools using massive amounts of computational power and underlying information that are being tracked by academics. Newer systems have been developed since the study and are more powerful.

The Stanford team gave GPT-3 a sentence or two from the actual Russian and Iranian propaganda, then instructed GPT-3 to create several versions of the summaries and to write short newspaper-like articles making the same point. Some of the original propaganda made demonstrably false claims, such as that Saudi Arabia would pay for Trump’s border wall, and that the President of Germany said 80 percent of American military drone attacks target civilians.

In other cases, the Russian and Iranian material took actual news events and added inflammatory assertions that were subjective at best. For example, one article about an American military strike in Syria, which was in response to a chemical weapons attack by the Syrian government on its own people, claimed the U.S. government was masking its true intent: taking “control of the ‘oil-rich’ region in eastern Syria.”

More than 8,000 survey respondents were randomly shown the actual propaganda and the AI-produced versions, and then asked what was persuasive. About half of the respondents were persuaded by the real propaganda. Those persuaded by AI amounted to only a few percentage points less. In other words, AI’s content was nearly as persuasive as human-made propaganda. (These figures echo the studies of the emails to 7,000-plus state legislators and public comments to Idaho regulators.)

AI can be persuasive while not being truthful because AI language models are not inherently designed for fact-checking or evidence-based evaluation. AI language systems are trained on massive data sets, which can be pulled from the internet or uploaded via a user’s information. The algorithms look for the next word in a sentence and then construct paragraphs and narratives. Thus, that mathematically driven approach can produce coherent, confident-sounding assertions and falsehoods, which have been labelled “AI hallucinations.” (This computational technique is similarly used to create or alter photos or videos by finding the next likely pixel in an image. Likewise, AI copies voices by looking for the next likely sound wave.)

While the Stanford study concerned AI mimicking written foreign propaganda, Stamos said that the emergence of large-language tools will now supercharge the way that U.S. political campaigns will create and use targeted advertising at platforms like Facebook and Google. That engagement runs the gamut of political activity, from more innocuous goals of fundraising and recruiting volunteers, to the darker arts of distracting the public and manipulating attitudes and behavior.

In recent years, campaign staffers or contractors typically would create and test a handful of ads aimed at a specific audience in a specific locale, Stamos explained. The campaign staff would instruct the social media platform’s interface to highlight messages or deliver the ads to these niche groups. The Trump campaign’s use of Facebook ads in 2016 epitomized this approach. As Bloomberg was first to report, they used disinformation to discourage Democrats from voting. Since then, online messaging has evolved to include made-up texts, tweets, comments, hashtags, emails, fake personas and web pages, and supporting assertions and arguments.

Stamos said that AI could supercharge this labor-intensive process by automating the content creation and mass-testing of what content is most engaging, which could be measured by viewership, e-mail responses, and donations. AI could also use the most engaging content to trigger the social media architecture that features the trending posts more prominently, giving false information undue and unearned attention.

“We have a model where you could prompt a system to create 1,000 potential ads, 1,000 voiceovers for this video, [then] test them across 20 different or 100 different advertising segments,” Stamos said. “You could have a really aggressive manipulation of people at very small scale.”

Political ad makers themselves are trying to put some guardrails on their industry—or, at least, suggesting that they are trying to be proactive.

The American Association of Political Consultants formally urged its practitioners to not use deep fakes—forged photographs, videos, or audio. Online campaigning experts also have said that AI has many positive uses, even if they caution its outputs should be vetted by humans so they don’t backfire by alienating recipients. For example, AI can parse big data sets, such as registered voter lists and voter histories, and analyze election results like voting patterns at the precinct level. Unwieldy voter databases can be broken down into manageable walking lists with maps for neighborhood door-knocking. AI can produce customized scripts with talking points tailored to specific voters based on profiles of their online activities and interests.

The Democratic National Committee has already been using AI to write and test variants of successful fund-raising emails, said Colin Delany, a longtime digital strategist who embraces AI in the 2023 edition of his e-book, How to Use the Internet to Change The World – and Win Elections. “AI will almost certainly evolve more rapidly than any other slice of campaign technology in the next few months,” Delany wrote. “Campaigns and advocacy organizations can and will use AI to get more done in less time.”

More prominently, the Republican National Committee released a digital ad in April attacking Biden with dystopian imagery of war, ruin and chaos, followed by the credit, “Built entirely with AI imagery.” The screen text made clear the ad’s imagery was a portrayal of the future “if” Biden is re-elected, not anything that already happened on Biden’s watch. Furthermore, the RNC’s images looked like they came from a shoddy video game, not the real world.

The RNC ad was not the example of the worst AI can do to the pillars of democracy. It was the sort of histrionic political ad that is already commonplace and can just as easily be created with existing animation software. Yet it sparked a flurry of hysterical reporting and pontificating. Representative Yvette Clark of New York quickly responded to the outcry with a reasonable, though modest, bill that would require campaigns to disclose the use of AI in their ads. But the bigger concern, as the Stanford research highlights, is the use of AI by adversarial, authoritarian governments and domestic influence operations to make it impossible to discern what is real and what is not.

And further down the line, as the new versions of AI more closely mimic the brain, some renowned chatbot engineers are worried that AI will independently make decisions—without human oversight—that can harm society, such as using weapons, or causing computer-led chaos or “extinction” on par with nuclear weapons or a pandemic.

Notably, some of the most urgent calls for slowing down the private sector’s rollout of generative AI and for federal regulation have come from AI developers, who are facing pressures to release new products before their impact, flaws, or misuse are known.

In March, technologists circulated a petition calling for a six-month pause on AI experiments until industry standards could be instituted. Nearly 28,000 people have since signed on. As The New York Times columnist Ezra Klein noted, AI insiders “are desperate to be regulated, even if it slows them down. In fact, especially if it slows them down.” In mid-May, OpenAI’s CEO Sam Altman testified before the Senate and agreed that some federal regulation would be welcome, so that the technology does more good than harm. Altman was among the signatories of a late May statement that said, “Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war.”

But Silicon Valley is not in agreement with how to proceed. Meta—which owns Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp—in February put one chatbot code online (with computational power on par with GPT-3) to spur innovation. Silicon Valley knows AI’s introduction is an inflection point, which, if handled poorly, could upend today’s industry giants. Thus, according to The New York Times, spokespeople for Google and OpenAI expressed fears that “A.I. tools like chatbots will be used to spread disinformation, hate speech and other toxic content” and, in turn, “are becoming increasingly secretive about the methods and software that underpin their A.I. products.”

Meta’s code, according to the Times, soon was found on the online message board 4chan, which is a notorious source for misinformation as well as hate speech. Last year, an engineer used 4chan threads to train an AI model that posted over 30,000 disturbing, anonymous online comments.

Microsoft, which has added OpenAI features to its search engine Bing, has tried to soothe the public’s nerves by publishing a framework “for building AI systems responsibly.” One bright line drawn by Microsoft: the company will not pair language-generating AI with “technology that can scan people’s faces and purport to infer their emotional states.” Depending on your perspective, you might be reassured that such a firewall exists, or unsettled that such a firewall is needed.

In fact, the efforts by the leading AI developers to establish some norms around its use and licensing have not been consistent. Even OpenAI has changed its standards, scholars have reported.

Researchers like Stamos have been discussing possible mitigations, including federal regulation, for several years. A January 2023 paper, by representatives of Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology, OpenAI, and Stanford Internet Observatory summarized proposals from a workshop held in late 2021, though the scholars cautioned none of their ideas were panaceas.

For example,regulators could constrain how the languagealgorithms are built, placing limits on exploiting copyrighted materials or scraping the web for personal information. They could mandate digital watermarks that make it easier to detect AI’s presence. They could require licenses which would effectively restrict access to the most advanced AI systems.

A nervous industry, recognizing a nervous public, is beginning to produce its own regulatory ideas. In late May, Microsoft president Brad Smith supported a requirement that systems used in federally determined “critical infrastructure” should have emergency braking systems or have the capacity to be turned off. He also urged Congress to enact labelling requirements for consumer products. Moving in that direction, a New York City law will take effect on July 1 to require disclosure if AI is used in hiring and promotion decisions. There also is a nascent AI-detection industry emerging in Silicon Valley.

Nonetheless, in the short run, as Stamos warned in the Stanford webinar, Americans should expect to be inundated with AI content in 2024’s elections.

“I think it is going to become really critical around images and videos to have the evidence that things are real because we’re also going to enter this situation where everybody can deny everything, right?” Stamos said. “As realistic a threat as people being convinced of [made-up] things, is that when things actually happen, we’re going to end up in this nihilistic age where nobody believes anything because the amount of BS that’s generated is so huge.”