Blockchain Ballots? Pilot Project in Denver Will Permit Independent Audit

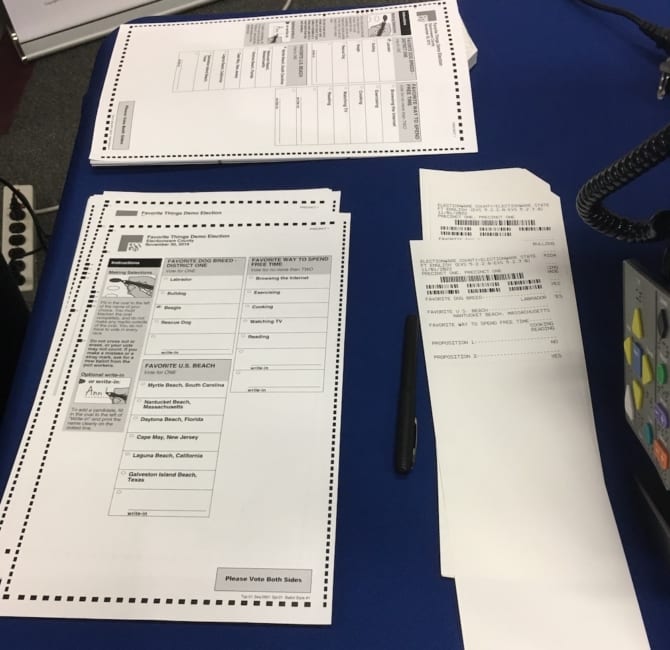

(Photo / Steven Rosenfeld)

The debate over online voting—whether an electronic ballot can be sufficiently trusted—is heading into a higher orbit in Denver. City election officials will open their pilot of the nation’s most advanced smartphone mobile voting app that several hundred overseas residents will use in May’s elections to independent examination by observers.

“We wanted and we asked Voatz [the app maker] to develop a means by which outside observers can conduct their own audits independently of the election conducted through the blockchain,” said Jocelyn Bucaro, Denver deputy director of elections.

The blockchain is a way to secure data by putting encrypted, unchangeable pieces of a file, in this case an electronic ballot marked by a smartphone, on computers in different locations that later will be reassembled, printed and counted with other ballots.

“We are hopeful that by the time that we are actually tabulating results for this election, we will have an offering… to be registered election observers through the blockchain to conduct their own audit of what we are reporting,” Bucaro said.

“We’d be the first entity ever to do a third-party digital audit of an election,” said Forrest Senti, Business and Government Initiatives director at the National Cybersecurity Center (NCC), based in Colorado Springs, which has worked with Denver for the past year to plan the pilot and will set up the ballot-handling audit including outside participants.

Observers can assess an “end-to-end verifiable” process, the city’s announcement said. That technical phrase is key, as it is the exacting security and accountability standard that academic critics of online voting have said must be satisfied before considering its use.

Many critics have never expected a voting system developer to assert they can meet that “end-to-end” standard. For years, they have said, and many still say, that software has holes that can be exploited to tilt election outcomes. That conclusion has bolstered the argument that there is no substitute for human-made ink marks on paper ballots. Some leaders in this community were neither impressed with Denver’s staging of an audit inviting skeptics nor even curious about the technologies involved.

“That’s not good enough,” said Jim Soper, a computer programmer and election integrity organizer. “An audit is not a red team test—a hack test,” he said, adding, “A lot of critical outsiders would not participate… They will invite their own people who will not be as critical or as skeptical as they need to be. We have seen this kind of stuff before.”

“Our country is moving toward paper ballots for a reason. Software is hard. Even the most long-term, experienced voting system vendors in our country cannot get it right—and this is a newbie start-up, who comes in with an app, who claims a bunch of stuff,” said Susan Dzieduszycka-Suinat, founder of the U.S. Vote Foundation, which for the past 15 years has helped overseas voters. “We’re trading one set of problems for another set of problems, and we’re equally unprepared for the new set.”

These hard responses reflect views that were formed when the manufacturers of paperless voting systems over-promised and under-delivered the machinery that many states bought after Florida’s flawed 2000 presidential election. Today, most of the country has gone back to using voting systems built around paper ballots. But what Denver is doing is not resurrecting these old and flawed systems, and it could have far-ranging implications.

Local Pilot, National Stakes

The city’s use of a mobile voting app, following 2018 pilots in West Virginia, is part of a bigger play that could reshape how millions of Americans vote. In short, the smartphone would replace what voters do when they sign into a poll book at a precinct, and then the phone would be used as a ballot-marking device—an electronic pen. The ballots, which are created by the election officials, would be copied and carried by the blockchain.

More specifically, a smartphone’s features are being used to credential the voter; verify their government-issued photo IDs; test that the person using the device is alive and not an avatar or fake; bind that phone to that voter and one ballot; and submit the ballot via the encrypted blockchain. Voatz and its allies in philanthropy, policy and government circles see smartphone voting as a potential option for major slices of society: citizens abroad, people with disabilities, and even states and counties that now vote by mail.

“That’s why we are doing this in the first place. We want to be able to bring people into the room and be able to understand that potential,” said Senti of the NCC, which spent a year assessing the city’s election infrastructure, creating technical guidelines for using blockchains in elections, vetted vendors and will oversee the open audit.

“We are going to have some people from the E.A.C. [Election Assistance Commission, the federal agency regulating overall voting systems] here at the end of the month and be able to have that conversation, and say, ‘Look, we’re leaving these people that want to test these technologies and bring these pilot opportunities to markets, and to provide a voice,’” he said. “The UOCAVA [overseas] population is 3.3 million registered voters, and the turnout is around 7 percent. That is an election [margin in a national race].”

Rarely has a local trial involving so few voters had such big stakes hovering overhead or behind-the-scenes players pushing for a new paradigm. But what is unfolding in Denver didn’t appear overnight. It is a result of many factors, including the absence of actively engaged federal arbiters in recent years—agencies whose reports inventorying internet voting globally or assessing voting system threats have not anticipated the building blocks of the Voatz app, or briefly discuss what the app uses to verify identities.

“It is unfortunate. There’s no federal standard to vet a system like this. I don’t know if they will ever create a standard to do something like this,” said Nimit Sawhney, founder and CEO of Voatz. “The new VVSG 2.0 [EAC’s Voluntary Voting System Guidelines] standard allows this [app] to be a part of a bigger voting system, but not a primary voting system. So it might be a while before you see these standards at all. So, in that regime, that scenario, we have to rely on third parties, and those third parties include the FBI, DHS and all those people [at think tanks, in philanthropy and government] as well.”

The technologies that are the building blocks of Voatz’s system underscore how the ground beneath the online voting debate has shifted. These recent developments are the emergence of biometrics as security features in smartphones (2013), the use of blockchains, or distributed ledgers, in finance—notably for cyber-currencies (2016), and a digital identity proofing industry that has grown in recent years.

A 2011 EAC report discussing surveying internet voting, after noting that “a single comprehensive standard for developing and testing internet voting does not exist,” says that election jurisdictions must make their own judgments about “the risks associated with multiple voting channels.” The report emphasizes that every voting system has trade-offs. The open question is where to draw the line on risks in the process.

When asked, Denver’s Bucaro said it was easy to assess risk when it came to a pilot for several hundred overseas voters in a local election.

“We are only using this for a population of voters that already, under federal law, receive their ballots, and, in Colorado, can cast their ballots electronically,” she said. “So, for us, the decision was a bit simpler, because one question we wanted to answer was, ‘Was this more secure than what we were otherwise offering to our military and overseas citizens?’ And the answer is yes. This is a more secure method than asking our voters to fill out their ballot online and return it to us as an email attachment. That’s easy.”

Thus, what Denver and its partners are doing is using a pilot to assess new technologies in a real-world setting, which is how new voting systems or any technology evolves, said Larry Moore, the former CEO of Clear Ballot, which pioneered the use of digital ballot images to account for every vote cast in an audit, and who is advising the start-up.

“We are not saying today that the Voatz system should be rolled out to millions of voters. No one in Voatz is saying that,” Moore said. “What we are saying is that we are anxious to pilot this in real-world settings that cannot be simulated in a lab, where problems come up and we try to solve them in a way that is lasting and is true. It is only through real-world pilots that we can really make progress.”

To date, as Voatz’s critics accurately have pointed out, the start-up has mostly tested its app within trusted circles and has not said what it is doing to protect potential voter privacy concerns, as the app is using a lot of data via the smartphone.

Voatz and its allies say that more closed approach is because there is a history of critics, including some of the advisers who articulated the “end-to-end” security standard in a 2015 report from Dzieduszycka-Suinat’s organization, working to stop any online voting. Some even tried to sabotage a 2016 trial by putting up a fake online voting website to lure unsuspecting voters in a party-run caucus in Utah. Soper defended that effort as a “spoof” to show that what’s seen online cannot be trusted. “They are there to make a technological point,” he said.

But Denver’s pilot and invitation to third parties to independently audit the core of its system—the use of blockchains—opens a new chapter in this narrative. The pilot and audit could push the online voting debate into an orbit where specifics and new technologies are evaluated, even if it is not the red team hacking test that Soper seeks. Or it could be like Krazy Glue fortifying already hardened positions.

“I think if you are against any form of internet voting, chances are it’s hard to convince you,” Bucaro said. “However, I will say this. I think it’s beneficial to have skeptics in the room. I think the more skeptics we have, questioning every aspect of this, the better, because they may think of something that the developers didn’t consider. They may test it in a way that the developers didn’t test. So I think to have them at the table, even if we don’t convince them that this is something that can be secure—or even if we can’t sell it to them—having their perspective is still very important.”

Also Available on: www.salon.com