Democratic Presidential Candidates in Uncharted Political Waters as Key States Overhaul Their Primaries and Caucuses

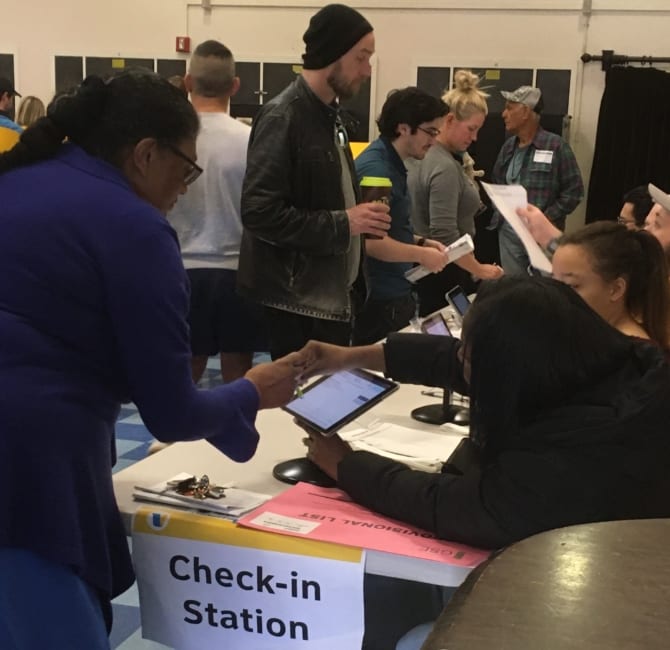

(Photo / Steven Rosenfeld)

Democrats in recent weeks have taken significant steps to reform the nominating process and voting in key states in anticipation of 2020’s presidential election and local contests.

Some of these steps bring voting protocols in big states like New York more in line with West Coast blue epicenters like California and Washington. Others are poised to bring unprecedented—and largely untested—reforms to the early presidential nominating contests, such as possibly using online platforms to participate in caucuses.

This week, on the first day of its session, New York State’s new blue majority legislature passed the most comprehensive package of election reforms in “over 100 years,” as the advocacy group LetNYVote.org put it. It created new early voting options, consolidated state and federal primaries, made voter registration portable (so residents who move do not have to re-register) and will begin pre-registering high school youths. Lawmakers also took the first steps toward adopting two state constitutional amendments to allow same-day voter registration and widespread voting by mail.

“This was an amazing and historic first step toward profound, structural voting reform in New York, and there is much still to do,” the coalition’s statement said.

New York’s actions come a few weeks after the Democratic National Committee issued its 2020 Delegate Selection Rules to modernize its presidential nominating primaries and caucuses. The rules seek to boost participation. They do so by requiring the caucus states to offer same-day registration and a way to participate from home—by absentee ballot or via an online platform. The rules don’t specify the technologies that state parties running caucuses will have to deploy. (State and county governments run primaries, in contrast.)

The new DNC rules are the biggest change in its nominating process in 50 years, which were last reformed after the turbulent 1968 Democratic National Convention and loss in the polls that fall to Republican Richard Nixon. While some previous caucus states such as Colorado will conduct presidential primaries in 2020, influential early caucus states such as Iowa and Nevada must follow the DNC’s new rules.

For example, Iowa Democrats—and any other voter willing to register with the party—will no longer have to spend several hours on a winter night at 1,679 caucus sites. In that traditional setting, voters gather in delegations backing individual candidates and vote in successive rounds, disqualifying candidates who get less than 15 percent of the total. The groups and their members cajole, bargain and realign themselves with new camps until the caucus results are final. (Iowa’s GOP conducts a presidential straw poll.)

In 2016, 171,500 Democrats participated in the Democratic caucuses. Kevin Geiken, the party’s executive director, said the DNC rules could boost turnout by 100,000 Iowans—with the vast majority taking part from home or remote locations.

“I think absolutely it’s realistic,” he said, when asked if turnout could double. “Because we will have the non-present participation or we will have that [technical pathway] solved by then. I think it will open it up to another 100,000 people right there.

The DNC’s new rules are guidelines. Each state must submit plans this spring detailing how it will conduct voting by mail and/or online voting for those not present. The rules also require an audit and recount process for disputes.

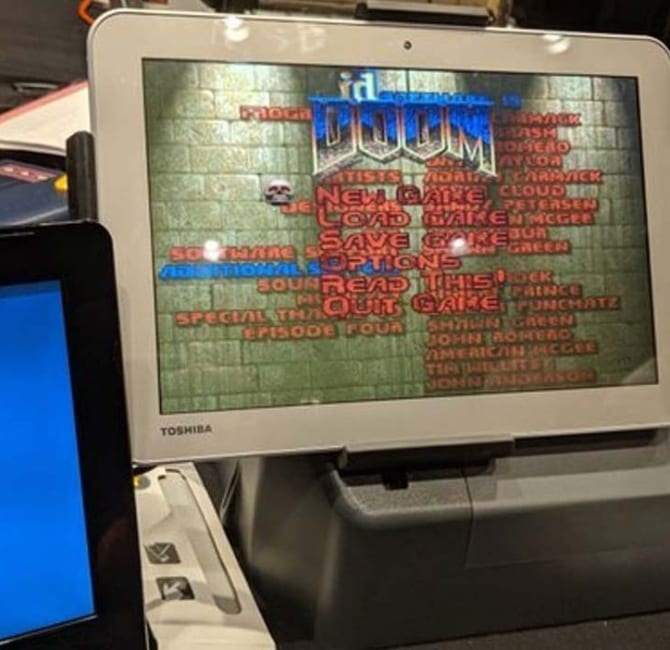

While the DNC is bullish about their 2020 caucus reforms, officials with experience administering elections are skeptical that so many changes can be well executed in the first election cycle they are unveiled. In 2004, Michigan Democrats offered an online caucusing option. In 2016, Nebraska and Washington used mail-in ballots.

In 2016, Utah’s Republican Party used an online platform for its presidential caucus. That process was closer to a regular primary election, where one candidate was selected, as opposed to successive rounds of voting that comprise an Iowa-style caucus. The report of the private vendor running the caucuses for the GOP noted that 90 percent of the voters who signed up to use it took part online. It did not explain why the other 10 percent did not participate—though one state election official this week said on background that thousands of people apparently tried but could not successfully log onto the online system.

In Iowa, the state Democratic Party is well aware of the challenges as it looks to 2020, Geiken said. He said the party would be working with Iowa stakeholders, consultants and voting technology firms to develop the details of how all this is supposed to work. But an online pathway to participate—a “tele-caucus”—was most in keeping with the caucus’ spirit, he said, offering his opinion but noting that the party has not made a formal decision.

“We have spent many, many months and thousands of hours of conversations with a whole lot of different folks about what is the best solution,” Geiken said. “We’re in the process, literally this month, of crafting that into a draft of a delegate selection plan… To be completely honest, none of these potential solutions is perfect.

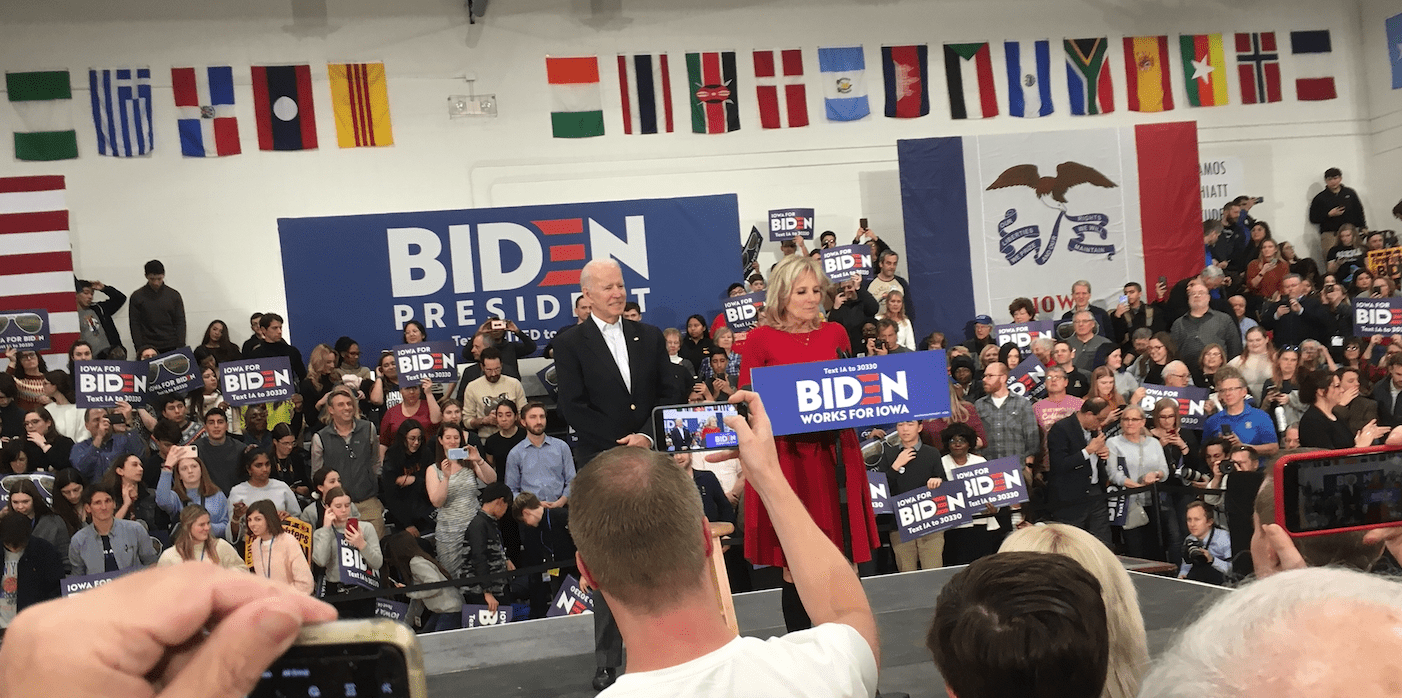

The DNC’s reforms affecting its first-in-the-nation nominating event—followed by a similar-style caucus in Nevada 19 days later—will not just change the way people participate on Caucus Day—or during the week before if an early participation option is offered. The 2020 reforms, and how state parties attend to details—such as possibly sharing its data on who wants to participate online—will affect how campaigns target voters.

For example, the most successful candidates in 2016 and 2018 did not rely on traditional ways to build their ranks and engage their supporters, several 2016 presidential campaign operatives said on background, which has tended to rely on lists of registered voters. The most successful campaigns bypassed the traditional gatekeepers, such as mainstream media. The DNC’s new rules should encourage more innovations in 2020, such as using text platforms to send messaging that can be shared on personal networks.

But looking toward the finish line, the biggest challenge facing the caucus states will likely be coordinating the rounds of voting and ensuing tabulation.

“No state’s election system is simple,” said Wesley Hicok, a procedural specialist and trainer in Iowa’s Secretary of State office. “A simple statement like ‘I’d like to remotely participate in a caucus system’ seems like a relatively innocuous request until you start thinking about how is this logistically going to work.”

Hicok said Iowans are used to high voting standards, at least in government-run elections, as opposed to what can be chaotic citizen-led presidential caucuses. The Des Moines Register, the state’s leading newspaper, editorialized after 2016’s Democratic caucuses that the stakes were too high for the mistakes it had witnessed. The GOP is not immune either. In 2012, the GOP mistakenly announced that Mitt Romney won its presidential straw poll, when, once all votes were counted, Rick Santorum had won.

But Geiken said the Iowa party has no choice but to figure out how to implement the DNC’s new 2020 delegate selection rules.

“That’s exactly where we are,” he said. “But it is the right goal to increase participation.”

Also Available on: www.alternet.org