Election Deniers Still Don’t Know How Elections Work

(Image: www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=444141447881221&set=pcb.444141681214531)

The 2022 general election has many takeaways. But apart from the winners and losers from political and policy perspectives, one obvious, lingering, and disturbing result is that election-denying partisans still do not know how elections work.

Across the country, activists – mostly Trump Republicans whose candidates lost – are claiming the results are inaccurate and illegitimate. Their criticism and demands, including calls for new elections, are based on misperceptions of how ballots are obtained, cast, and counted.

The accusations are not just in high-profile battleground states like Arizona, where supporters of Trump-aligned candidates who lost bids for governor, secretary of state and U.S. Senate are planning a state capitol protest to demand a new election on Friday, November 25.

Consider the following examples from ElectionLine.org, which collates press reports from around the county on election administration and policy issues.

• In Forsyth County, North Carolina, the state’s fourth most populous and home to the Winston-Salem metro area, confusion over software used to shut down polling place voting computers on Election Day led Kenneth Raymond, the county’s Republican Party chair, to allege that a “security breach” could have occurred. He called for a “full forensic” investigation; a term thrown around by election deniers that is an open-ended inquest that can perpetuate doubts.

Forsyth County’s election director, Tim Tsujii, at a Board of Elections meeting, acknowledged the apparent programming mistake but said it would not have affected vote counts. All of the paper ballots at two randomly chosen precincts were hand-counted and they matched the electronicly compiled totals, he said, attesting to the voting system’s accuracy.

• In Dallas County, Texas, electronic voter rolls, called e-poll books, which are used to check in voters before they receive a ballot, are updated throughout the day. That is done to ensure that the number of voters and ballots match, and to prevent anyone from voting more than once.

However, partisan observers at polls claimed on social media that they saw data on voter rolls repeatedly “jump,” saying, “Think about it, this time, the fraud is so undeniably obvious. It happened in every state, in every county.” USA Today’s fact-check team said, “We rate FALSE the claim that a Texas voting machine [was] adding voters as polls close was election fraud. E-poll books in Dallas County encountered a processing delay that resulted in data from already checked-in voters being downloaded after polls closed.”

The contrast between racy conspiratorial claims and more boring factual reality can be striking. It often takes years to understand how election law, polling place procedures, and the data in voter rolls and voting counting computers interact – to get the correct version of a ballot into a voter’s hands, and then to correctly detect and count a ballot’s votes.

Partisans who are new to this arena often don’t realize what checks and balances follow the complex steps in the process. They suspect – or have been led to believe – that anything that is not immediately apparent is suspicious or cause for alarm.

Last week in Delaware County, Pennsylvania – a populous Philadelphia suburb – two GOP poll watchers and an unsuccessful Republican candidate for state representative filed a petition for an emergency injunction to delay the certification of winners.

They cited a blizzard of detailed claims. The county had mailed out ballots to “unverified voters.” It had deleted mail ballot requests for others. It had allowed “a partisan third party to control and handle mail ballots.” It took “hours” to return paper ballots and flash drives from ballot-counting computers from polling places to headquarters. The process was anything but simple and transparent.

A day long court hearing led a county judge – who allowed those suing to present witnesses – to comment from the bench that “he had not heard any testimony to even suspect fraud or bad actors… and that he became more and more convinced as the hearing went along that [election board attorney Nick] Centrella had correctly identified the petition as an election challenge [to the unofficial results],” a local newspaper reported on November 23.

Election officials and workers do make mistakes with setting up and operating the multitude of computers and paper records used in voting. But occasional mistakes do not man that elections are being stolen, which is the default posture of many disappointed Trump Republicans.

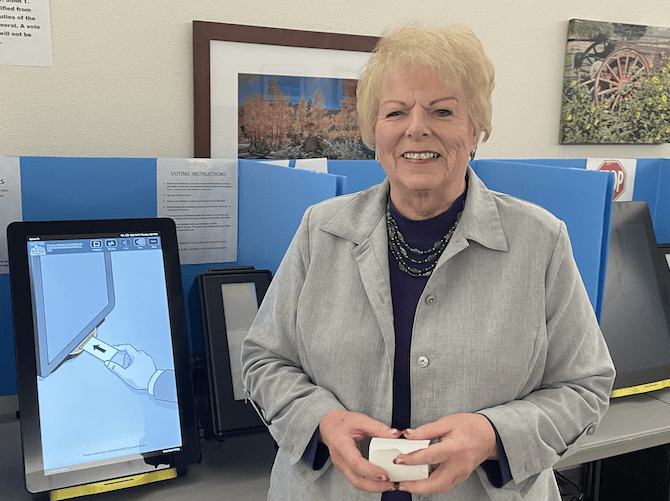

On November 17, Liz Harris – one of Arizona’s most fervent Trump Republicans who is ahead in her 2022 bid for state representative by 270 votes (triggering a recount) – said on Facebook that “we need to hold a new election immediately” due to “clear signs of foul play.” She cited “machine malfunctions, chain of custody issues and just blatant mathematical impossibilities.”

“I will now be withholding my vote on any bills in this session without this new election in protest to what is clearly a potentially fraudulent election,” she wrote.

Whether Harris takes a less draconian view after the forthcoming recount in her race is an open question. But in nearby Nevada, Mark Kampf, the clerk of Nye County and a 2020 presidential election denier, is doing something that no other Trump Republican is doing.

Kampf, a retired corporate auditor for Fortune 500 companies, is conducting an unofficial hand recount of the general election’s paper ballots. Kampf and other Trump Republicans, including Nye County’s supervisors, said that they did not trust their voting system’s computers.

“On Wednesday, more than 12,000 ballots had been counted in Nye County, Kampf reported, with 99.89 percent accuracy compared to results from electronic machines,” the Pahrump Valley Times reported on November 21. “We’ve learned a lot,” he told a local TV station.

Was the electronic vote-counting system perfect? No. But a 99.89 percent accuracy rate and insights about where minor variations occurred is a far cry from claiming an election was stolen, and election workers and voting system computers cannot be trusted.