Georgia to Use New Audit Tool to Assess Vote Count Accuracy—Is It Ready?

(Image: https://sos.ga.gov/)

As the nation’s eyes turned to Georgia on Friday, where the latest returns have boosted Joe Biden’s prospects for the presidency and where likely runoffs in two U.S. Senate races could restore Democratic control to that body, the state must first audit its unofficial vote totals before a presidential recount can begin—should President Trump seek a recount.

That next step, called a risk-limiting audit (RLA), is a new and barely tested process in Georgia. Whether the forthcoming RLA will be targeted by President Trump’s campaign lawyers is an open question. But Georgia’s audit will be the highest-profile test yet for an obscure process that was created by statisticians to convey public assurance that vote counts can be trusted.

Georgia hopes to finish counting all of its 2020 election votes by late Friday, Gabriel Sterling, Georgia voting system implementation manager, said midday Friday. The state’s 159 counties then finalize and certify the results, totaling the legally cast ballots. Then comes the RLA.

“State certification [of the winners] can come only after we do our risk-limiting audit,” Sterling said, explaining the steps. “And that is going to be the first time that the state is doing it. It was part of H.B. 316, Secretary [of State Brad] Raffensperger’s election reform law. So that [audit] happens, and then we are going to have the state certification. The outward bound [deadline] of that [state certification] is [Friday,] November 20.”

“Our hope and intent in working with the counties is to move that earlier,” he continued. “And at that point, whoever comes in second, either President Trump or Vice President Biden, either one of them, whoever is in second place, can request that recount.”

Walter C. Jones, who leads the secretary of state’s voter education efforts, said the RLA would likely occur earlier in the week of November 16.

Estimating Accuracy

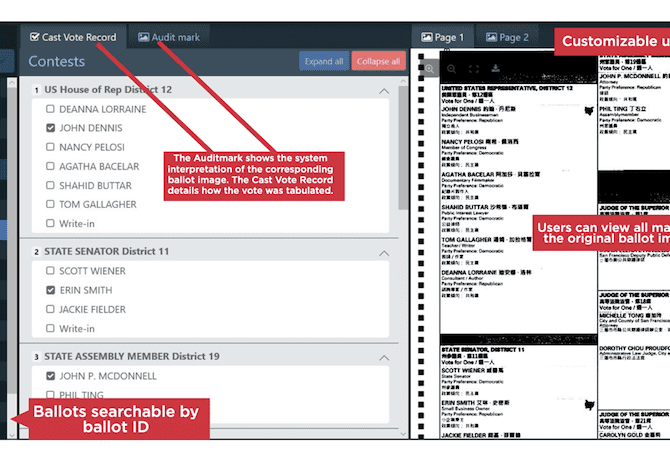

The audit is an exercise that will assess if the electronic totals from a county’s central tabulators match randomly sampled paper ballots. The RLA is based on a statistical formula where auditors set an accuracy level, which is usually 90 or 95 percent. If the manually examined and counted votes from the paper ballots do not match the electronically compiled results, then more paper ballots are randomly pulled until the accuracy level is reached.

A risk-limiting audit typically looks at one race—not every race—on the ballot to produce its confidence estimate. In most cases, a noncontroversial contest with a large winning margin is picked, as a wider margin translates into examining fewer ballots—given the formula’s math.

For example, in an RLA pilot conducted after the problematic June 9 primary in Fulton County, Georgia—one of four such tests conducted in the state—county officials only needed to examine 27 random ballots to have 90 percent confidence in the electronically totaled results. That number of ballots drawn was small because Biden won 84 percent of the county’s Democratic presidential primary, a contest where 160,000 votes were cast.

When asked how Georgia planned to conduct its RLA after a presidential election, where, as of midday Friday, the margin between Biden and Trump was about 1,600 votes out of 5 million ballots cast, Jones said that the state would not audit the presidential race, but instead pick a down-ballot statewide contest such as public service commissioner.

“We’ll essentially do it from a statewide race,” Jones said. “The [RLA] algorithm will then say, in County A, Precinct 22, pull out the ballot that is the 300th in the stack. And in County B, in two precincts, pull others [specified ballots] out. We’ll instruct the counties to do that. I don’t know if it will be some kind of Zoom call or conference call or if we’ll just send an email [to county officials] and they just send us the results and we’ll total it up.”

A California-based nonprofit, VotingWorks, is advising Georgia officials on the RLA, he said.

What Will Be Audited?

Indeed, an RLA based on Georgia’s statewide presidential results would not be expeditious, as it would evolve into almost a full recount, which is a different legal process that is only supposed to occur after the results are certified.

That’s because a statewide RLA based on the presidential votes where the margins are so close—1,600 votes out of 5 million votes cast—would turn into a “full hand count” of almost all ballots, according to the audit tool created by RLA’s creator, University of California, Berkeley, mathematician Philip Stark, that calculates how many random ballots have to be examined. The number of paper ballots grows exponentially as the winning margin shrinks.

While top Georgia election officials expressed confidence in their voting systems Friday and underscored that there had been no voter fraud, whether or not the RLA would be accepted by voters in the state and across the U.S. is an open question.

Whether an accuracy estimate based on a down-ballot race would be accepted or attacked by Trump’s campaign is more easily answered, especially if the votes cast in his election were not examined in a process that was intended to judge the accuracy of the state’s overall vote-counting technology.

Under any scenario, Georgia’s RLA will be the highest-profile test to date.

Meanwhile, whether or not there is a presidential recount in Georgia does not depend solely on that state. Trump’s team has to assess the unofficial margins in other battleground states where he has been trailing, as part of its strategy to assess his path to a second term. It may be that Trump will not file for a Georgia recount if he loses by wide margins in Pennsylvania, Nevada and Arizona.