Here’s What America’s Election Experts Think It’s Going to Take to Fix Our Democracy

(Image / www.aoc.gov)

As the vote counts are finalized and the dust settles on California’s June 5 primary, one thing that’s clear is the pre-election predictions and fears about its “top-two” system, where the two top vote getters, regardless of party, face off in the fall, were wrong.

The system, which was instituted in 2010 and backed by then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, a Republican, was promoted as elevating more moderate candidates. The 2018 primary showed that wasn’t the case. Democrats, echoing other 2018 primaries, saw swarms of grassroots-backed progressives and fewer party-backed centrists face off. Republicans saw a mix of incumbents and challengers standing with President Trump or ignoring Trump while playing up local ties. In both cases, the political middle was barren.

And the two major parties, for different reasons, thought they would be shut out of the fall ballot—and that didn’t happen either. Democrats feared too many candidates would dilute their numbers, giving the GOP a boost; Republicans feared too many Democrats would keep them from placing second. So the major parties, once again, showed they hold more sway than widely assumed, and can’t be so easily dislodged.

There’s a big picture lesson in all of this for political reformers—one that some of the nation’s leading election law scholars noted at a recent Stanford Law School conference on the Constitution and Political Parties. That lesson is there is no silver bullet, or single reform, that’s going to fix the anti-democratic or uglier side of our political system.

“I want to start with that, because it introduces this idea of, ‘Just one more reform and we get things back. This is the next reform. We didn’t tinker with the last one just right,’” said Samuel Issacharoff, NYU Law School professor of constitutional law. “Let me give a catalog of some of the reforms that many of us who think about these things have been seduced by over the years, and I include myself. I’ve loved each and every one of these.”

Issacharoff’s ensuing confession was remarkable—and didn’t even include some of the latest solutions, such as New York Times columnist David Brooks pushing multi-member congressional districts (to theoretically have more ideological diversity) and ranked-choice voting (where voters list their top choices and the second- and third-place votes for the least-successful candidates are reassigned until a majority winner appears).

“‘Open primaries, not closed primaries,’” Issacharoff continued, referring to how parties in different states allow non-party members to vote in their primaries—or don’t. “That’s going to start getting the broader base. That’s going to make the parties more responsive than they are in general. [That will prompt] more participation, more democracy in the nominating process. That means that the citizenry will be more heavily invested… [but] what that gave rise to was the tyranny of a minority of the majority.”

“More funds into the party,” he said, citing another reform that might reverse the growth of outside independent spending. “Let’s start relaxing the campaign contributions into the parties themselves, as opposed to pushing it out. We’ve heard more of that today, and I believe in that or I believed in that, I thought that was a great idea… Allow coordination, allow parties to start maintaining some discipline over the candidates. That will empower the parties again. Or ‘more super-delegates,’ because that is more elite control, more peer review. Or ‘less super-delegates,’ because that’s [not] anti-democrat. I loved them all.”

“The reason I raise this is, when you start having a catalog of reforms that are going to almost get you there and they keep failing, sometimes you’ve got to step back and say, ‘What is it that we’re trying to restore and what are the reasons that it is not taking hold?’” Issacharoff said.

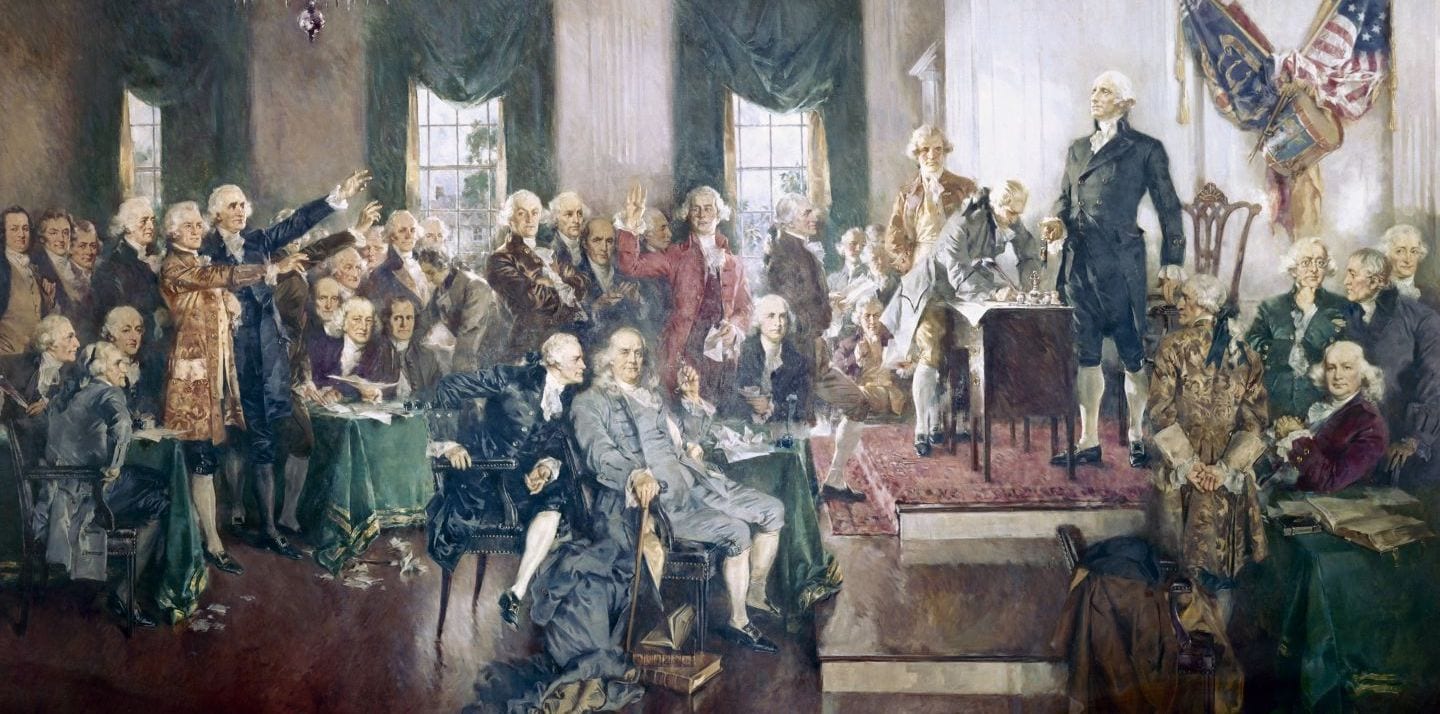

His answer partly was to remind people that political parties existed for many reasons that are easily overlooked today—even if there is frustration with the two major parties. They controlled the nominating process. They kept constituencies in line. They helped immigrant communities integrate into America by patronage jobs. They are the bedrock behind a functioning legislative process—or the opposite, which can be seen as political parties are collapsing in Italy, Spain, France and India and leaving vacuums.

“That’s shocking and that’s the pattern across the democratic world right now. So that leaves one element that the parties play that I think we underestimate its significance. Which is parties were the mechanism of transmission of ideas, interest, and loyalty between mass institutions, non-state institutions in the society, and the political process,” he said. “So that sense of the parties having some center of gravity outside the state was what gave the parties a sense of dynamism and made them responsive to the needs of the population. Once that fails, the institutional frailty of the parties becomes more and more apparent.”

Issacharoff is not defending today’s two major American political parties, per se. But he is asking the questions of what’s their useful roles, what’s not, and he’s urging political reformers to look at a larger landscape than a silver-bullet solution—as most reforms have not achieved their intended goals.

Going back to this week’s top-two California primary, the final results won’t be known for days because of the vote-counting process. But one thing that’s clear is the voter turnout was low—more in line with typical midterm elections than what’s been seen in other states where Democrats have come out in numbers suggesting this is a blue wave year.

Another Question: Why People Vote

Why more people didn’t vote is an open question. The press was telling Californians that their state could hold the key to whether Democrats gained a quarter of the seats needed to retake the House majority. In short, they were told the state held a big key to resisting Trump. There also were important local races, such as an open mayoral seat in San Francisco.

At the Stanford Law School conference, Burt Neuborne, who is the founding legal director of the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU Law School and has worked on civil liberties cases dating back to the Vietnam War, confessed that progressives have been losing election law cases for decades and said it’s hard to convince ordinary people that their votes really matter. On the other hand, he said voting was important to a person’s self-expression, dignity, sense of community, and noted that the political system is a reflection, for good and bad, of society at large. But rather than merely fighting in legal trenches to remove “transaction costs, things like voter ID, that are part of voter suppression,” Neuborne said he has begun to think a new priority is called for.

“So I think that we have to at least begin to think about how we increase the perceived value of voting. That is the only way we’re going to pull people in. I spent a career taking costs down, I want to spend some time now taking perceiving value up,” he said. “And one way to do it is the way we talked about yesterday. And that’s to get rid of gerrymandering once and for all. And to at least enhance the likelihood that there are genuinely competitive elections.”

“And the second one is campaign finance reform,” he continued. “I don’t accept the fact that we’re locked in an airless box, that we have to stay inside the existing [legal] parameters. To me, there are seven fundamental analytic mistakes that are there—waiting to be kicked over, and one of them will be kicked over in a way that will change. And I’ll just quickly summarize what the seven are, and then suggest some wiggle room.”

Neuborne’s starting point is the U.S. Supreme Court 1976 ruling, Buckley v. Valeo, was wrong to assert that spending money is a form of political speech deserving the highest First Amendment protections—more than picketing, other forms of protest or equality among citizens.

“I know this is an argument that has been lost and lost and lost and lost. [But] campaign spending is not pure speech,” he said. “It is communicative action, there’s no question that it’s communicative action. But why it has to be called pure speech, why it should receive more protection than picketing, why it should receive more protection than demonstrating, why it should receive more protection than burning a draft card as a form of protest. Why the spending of large amounts of money on a campaign should be characterized as more deserving of constitutional protection than other categories of communicative activity, I still don’t understand.”

“The second is, I still don’t understand why equality is not a compelling government interest, even if you go to pure speech,” Neuborne continued, referring to how the courts have eviscerated public financing schemes—to allow a more economically diverse slate of candidates. “The maintenance of political equality in this system is absolutely crucial to a strong and vibrant democracy, and if you don’t have it, your democracy is in trouble. And of course, the [Supreme] Court didn’t say it wasn’t a compelling interest. What they said was, public funding could be a less drastic means, but… made it very difficult to have public funding.”

Other Supreme Court rulings also were wrong he said. There’s no reason why political contributions should be regulated but political spending should not. Also, the current definition of political corruption in campaign finance law has become meaningless, he said, allowing operatives outside of campaigns and political parties to spend big to sway elections and curry favor with winners.

“I just want to put on the table… the idea that independent expenditures cannot result in corruption. That’s nonsense,” he said. “Everybody in this room knows that independent expenditures can. What the Supreme Court did is it froze the election cycle in single election, and it said because the person making the independent expenditure doesn’t have any connection with the candidate; therefore, there can’t be any corruption. Did they forget that people run for reelection? Did they forget that you might want to make it very, very useful for the person making the independent expenditure to keep making independent expenditures in future elections? So the chance for corruption is there.”

Right now, Neuborne thinks the one reform that might curb the extremism that marks today’s political arena is Congress regulating independent expenditures and loosening the restrictions faced by parties with raising money and spending it on candidates. Both the GOP and Democrats support that, he and other election law specialists noted.

“In other words, instead of letting massive independent expenditure votes on either side play disproportionate roles in the electoral process, tell them that that’s going to be regulated,” he said. “But if the money is cycled into the political party system, which really should be the engine that’s driving the electoral process, we can do that. That can be done, I think, with relatively minor tinkering with the existing system.”

Neuborne’s suggestion won’t address the frustrations that people on both sides of the aisle feel about the two major parties. But just as Issacharoff has spent decades looking at individual reforms and seen how they fail to deliver as promised, Neuborne’s suggestion doesn’t hinge on a new Supreme Court majority or a future constitutional amendment.

It looks at an outsized dysfunctional feature of a complex system and says start there. And it does that against a backdrop of millions of Americans who still cast ballots, even if they are frustrated or worse with the choice of candidates and political system.

Also Available on: www.alternet.org