Here’s What You Need to Know About Registering for the 2018 Election – Before Time Runs Out

Editor’s Note: The 2018 midterm elections are quickly approaching. These non-presidential elections historically give voters a chance to change the country’s course. They will decide whether or not Republicans keep a majority in Congress, important governor’s races, and more.

A Voter’s Guide to the 2018 Election, written by Steven Rosenfeld, senior writing fellow of Voting Booth, is intended to help new voters, infrequent voters and veteran voters have a better idea of what they must do to be able to vote and have their vote counted. The following is an excerpt from the guide, available in full here.

How to Vote, Step One: Get Registered

Every state except North Dakota requires residents to register to vote. This can be done in three-quarters of the states by going online, or by paper applications mailed in or filed in person.

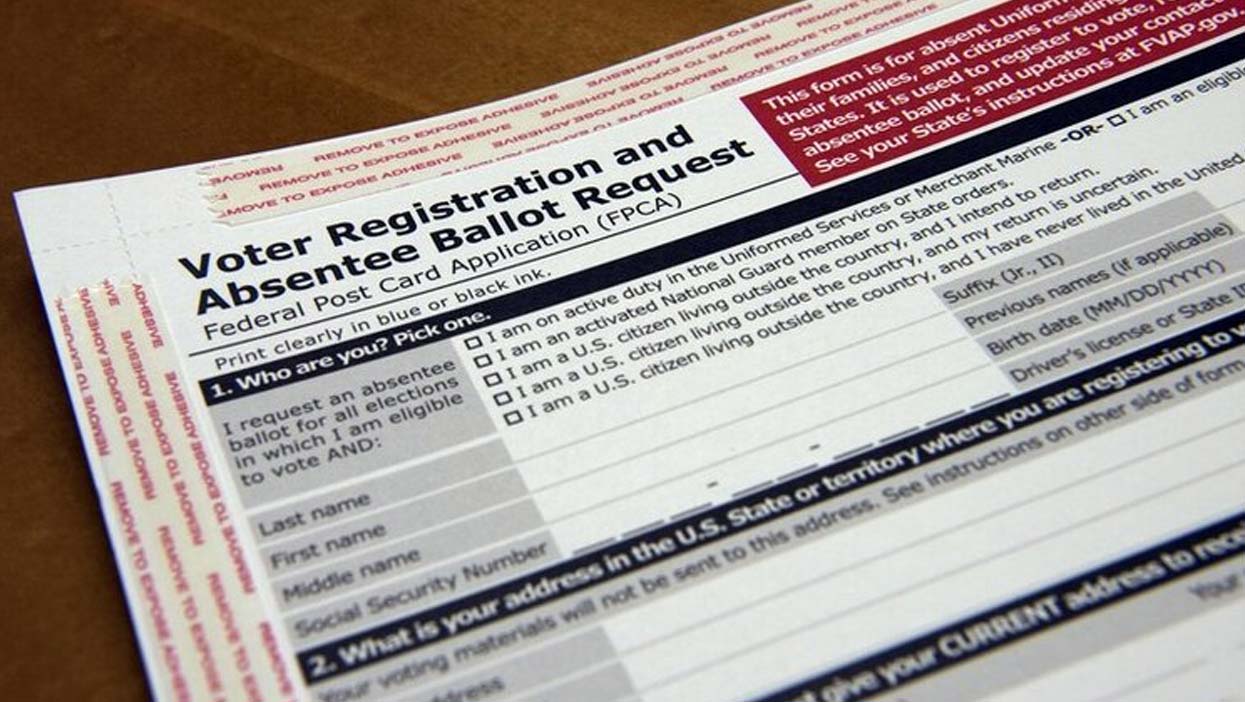

To vote in national and state elections in America, you have to be a citizen, age 18 or older, and register with your state before its deadline. In most states, that means going online to a state website and filling in basic information—or filling out and mailing in a paper registration form found at all post offices (or doing that in person at a county election office).

Increasingly, states are helping people to register. Thirty-seven states and Washington, D.C., offer online registration (here is a chart of those states). Motor vehicle agencies ask if you want to register when getting or renewing your license. As of mid-2018, 10 states are registering voters automatically when they get or renew a driver’s license, unless they opt out.

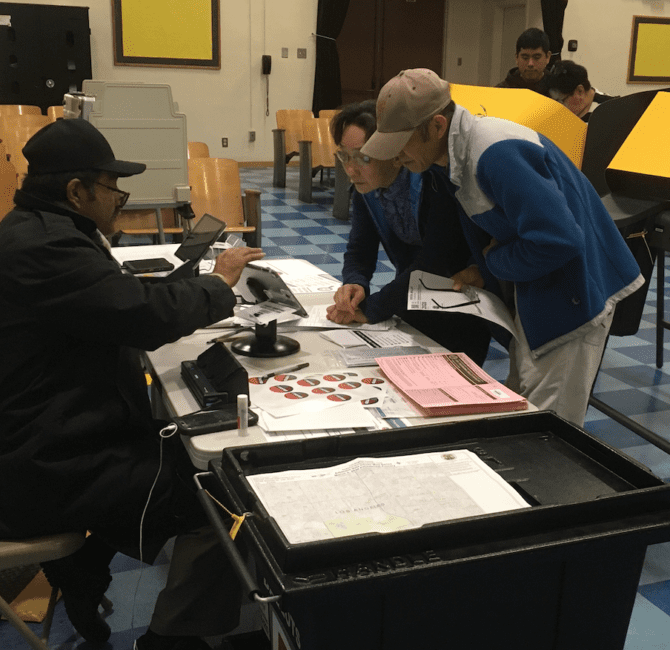

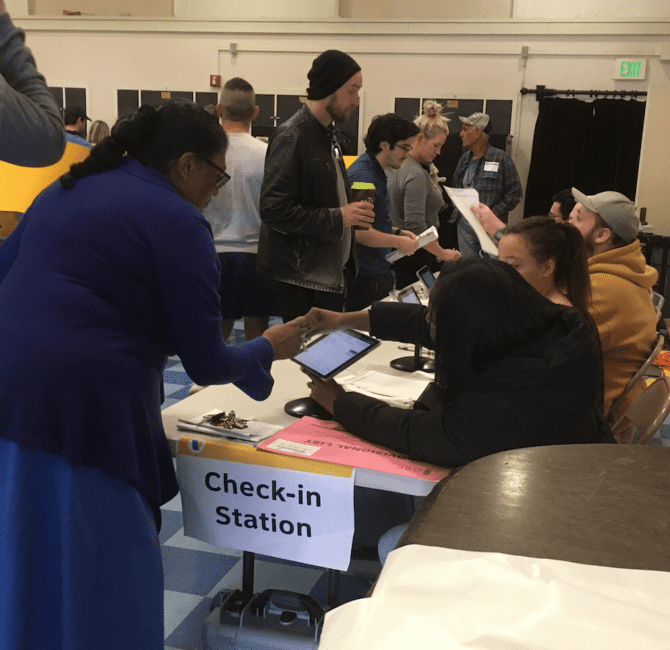

Seventeen states and Washington, D.C., also have same-day registration (see chart), meaning you can register and vote on the same day. In two of those states, Maryland and North Carolina, that option is only available during their early voting period (a window that ends before Election Day, which this fall is November 6, 2018).

While states have registration filing deadlines, it has never been easier to register. This chart has a state-by-state list of deadlines and same-day registration details.

What Information Is Needed?

You start by filling in your formal name (not nicknames!), residence address, mailing address (if it’s different from your home), date of birth, phone number or email (that’s optional—it’s used if there are any questions) and a government-issued ID number (usually your driver’s license or Social Security card number). Some states ask for your choice of political party. A few ask for race or ethnicity. Then you sign your name. (The U.S. Election Assistance Commission has this booklet with specifics for every state.)

Why do states want this information? An accurate home address ensures you get the correct ballot, as candidates and questions differ as you move from national to state to local races. The same goes for political party, whose primaries nominate candidates for the general election. State parties vary on whether anyone can vote in their primary if they have not already joined that party. (Independents have the best chance.) Race and ethnicity are for federal oversight—based on past state histories of discrimination.

Birthdays, driver’s licenses or Social Security numbers are used to verify identity. (The state will assign an ID number if you don’t have these government IDs.) These numbers are also used to keep voter lists current after people move, marry and change their names, or die. The signature is a legal oath that your information is true. It’s also printed in poll books at precincts, where you sign in to receive a regular ballot, and used in other ways—such as checking the ballot envelope if you’re voting by mail.

What Can Go Wrong?

Chances are you won’t misspell your name when registering online. But if you don’t register online and your handwriting is sloppy, a clerk in a county office could misread your name and put a typo in their computerized voter database. That snafu has led to people showing up at the polls and not finding their names in voter lists. That scenario is never pleasant—but can be resolved with patience (more on that shortly).

There’s another version of being sloppy when filling out a registration form (even online) that could come back to bite you: a messy signature. Make sure how you sign looks like what you normally do. Nobody wants a poll worker or party official to think that your signature does not match what’s on your registration form—which is in the poll book. That scenario also can be resolved, but it can be avoided by signing clearly.

Registering online is the best option. Once you’re in the system, you’re in it. The biggest complaint from officials about traditional voter registration drives is they dump a pile of paper applications to process at the last minute. In Georgia, the top state election official, Secretary of State Brian Kemp, a Republican running for governor this fall, did not process tens of thousands of paper forms turned in by a Democrat-led drive in 2014. (Stacey Abrams, now running against Kemp, led that effort.) We will skip Kemp’s rationale. Had those people registered online, they’d have avoided his obstruction.

How does one register online? Type “Secretary of State” and your state’s name into an online search, and a registration portal will appear. Register directly with your state—not with a group that may direct you to another portal. State governments, and then mostly counties, oversee elections. Cut out the middlemen. (Once registered, campaigns and activists will find you.)

Deadlines and New Voters

There are a few more things to know. Most important is that registration deadlines vary by state. The longest are 30 days before the next election. For 2018’s midterms, that falls in early October. Try not to wait until the last minute, as it may be harder to get someone on the phone should any questions arise. (This EAC booklet has state deadlines.)

The next thing is residency requirements. To vote, you have to be a citizen, be at least 18 and qualify as a state resident. Usually, that means living at the same address for 10 to 30 days. Residency mostly concerns first-time voters, especially students. They must decide between registering at their parents’ address (and getting an absentee, or mail-in, ballot from that home county) or registering where they go to school.

Sometimes, states and party officials oppose student voting. Students might hear scare tactics; such as that they could lose financial aid if they registered away from their parents’ home. That’s almost always not true, the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law noted, writing, “There is a lot of misinformation out there regarding what can happen to students.”

Nonetheless, students who want to vote have to think ahead and not be scared off. For example, Republican-led New Hampshire just passed a law (aimed at students) that new voters be permanent residents, obtain a state driver’s license with 60 days of an election and register their cars in the state. But it doesn’t take effect until 2019—not this fall.

Movers and Infrequent Voters

There’s another category of people who need to be mindful about their voter registration status—whether it’s current or they have to update their information. These are people who were registered voters, but moved (inside their county or state), or changed their names (usually by marriage), or vote infrequently (such as only in presidential years). If you moved to a new state, you have to re-register all over again.

Twenty states allow you to update your registration at a polling place, or they track voters who move and automatically update that information for them. If you’ve moved, married or are an infrequent voter, the smart thing is to call your local election office (typically at the county level) and ask if your registration is current. The U.S. Vote Foundation has an online searchable directory to contact these local offices and officials.

If you have voted infrequently but want to vote this fall, you should check your status. Federal law lets states remove (or purge) inactive people if they have not voted in four years—two complete federal election cycles. Some red-run states, like Ohio, that have sped up that four-year timetable have been sued but have won at the Supreme Court. Others like Indiana have tried to do likewise, but have been blocked in court. The easiest way to check your status is to call your local election office.

Not-So-Fine Print

Finally, there are people who have lost their voting rights. Imprisoned felons can only vote in two states—Maine and Vermont. Other states have a range of steps if those individuals want to vote. In some states like Oregon, they can vote as long as they’re not in jail. In other states, there’s a formal process to regain voting rights. In four states they are permanently blocked, although the state with the most felons, Florida, will this November vote on re-enfranchisement. In every election, a few ex-felons register without realizing they may be breaking the law. People found mentally incompetent by a court also lose their voting rights.

There’s one other potential hurdle in a few states. A few states require registrants provide proof of citizenship with their applications to vote in their state elections—as opposed to registering and voting in federal elections. (In all other states, you register for both at the same time.) Those states are Alabama, Arizona, Kansas and Georgia. They have slightly different versions of this policy. Georgia, for example, may request proof if its databases can’t verify one’s citizenship. (These states have some of the least voter-friendly laws.)

The twist of requiring additional proof beyond the eligibility requirements to register takes us to voter suppression. While voter registration is easier than it has ever been in most of the country, in some red-run states, the incumbents have embraced a menu of tactics to discourage their opposition’s base from voting. The most common tactic is requiring voters to present specific state-issued ID cards to get a ballot. (Other states simply have you sign in at the polls, as that’s a legal oath affirming your identity.)

To read the complete text of A Voter’s Guide to the 2018 Election, click here to view online, or click here view/download the full guide as a pdf.

This article was produced by Voting Booth, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Also Available on: www.alternet.org