The Supreme Court Just Dealt Another Big Blow to Our Voting Rights

(Photo / http://www.ohiostatehouse.org)

This week’s Supreme Court ruling upholding Ohio’s Republican-led voter roll purges may end up as one of the decade’s most consequential anti-voter rulings, shadowing its 2013 ruling gutting the National Voting Rights Act’s enforcement provisions.

The Court’s conservative majority, in a 5-to-4 ruling, applied a narrow technocratic reading of the National Voter Registration Act of 1993 (NVRA) over the method that Ohio removed registered but infrequent voters. The NVRA laid out a process where someone who did not vote in four years—two cycles—would get a postcard informing them of their inactive status, and pending removal, if they didn’t vote in the next federal election.

But the NVRA’s wording was ambiguous, laying out a four-year trigger for starting the removal process, but elsewhere stating voters couldn’t be purged “by reason of the person’s failure to vote.” Ohio’s Republican Secretary of State, Jon Husted, seized on that ambiguity and created a “supplemental process” accelerating the removal process. Husted mailed cards to inactive voters, which, if not returned, hastened their purge from the voter rolls.

What was additionally devious—and partisan—about Husted’s new process was that it was disproportionately used to purge registered Democrats from Ohio’s urban epicenters, while removing far fewer Republican voters from surrounding suburbs. Investigative reporters from Reuters found twice as many Democrats were purged in Cleveland, Cincinnati and Columbus as were purged in the surrounding suburbs.

However, Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr., writing for the majority, addressed the narrow letter of the law—the technicalities of the voter notification and removal process—as opposed to the spirit of the national law to expand voter registration opportunities.

A key NVRA provision, Alito wrote, “simply forbids the use of non-voting as the sole criterion for removing a registrant, and Ohio does not use it that way.” Instead, “Ohio removes registrants only if they have failed to vote and have failed to respond to a notice.” In other words, Alito said that Ohio did not simply purge people for failure to vote, as the law forbid.

The Court’s more liberal justices strongly dissented. Justice Stephen Breyer noted that Husted cast an unduly wide net and removed many voters due to “the human tendency not to send back cards received in the mail.”

Justice Sonia Sotomayor said the Court’s conservatives turned the NVRA inside out—using a pro-participation law to make it harder to vote.

“Ohio’s Supplemental Process reflects precisely the type of purge system that the NVRA was designed to prevent,” she wrote in a dissent. “Under the Supplemental Process, Ohio will purge a registrant from the rolls after six years of not voting, e.g., sitting out one Presidential election and two midterm elections, and after failing to send back one piece of mail, even though there is no reasonable basis to believe the individual actually moved.

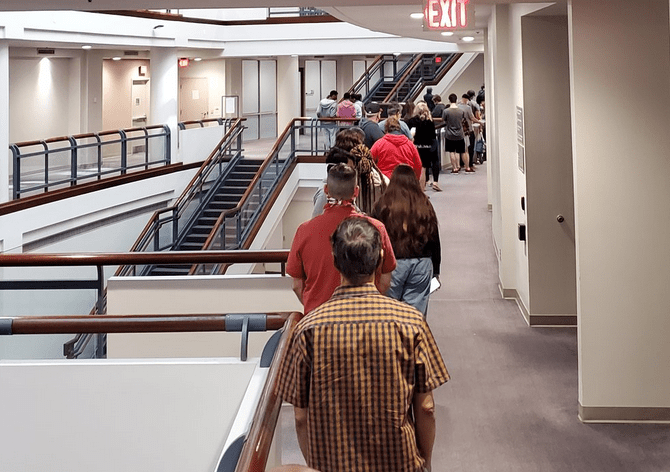

Sotomayor, citing briefs filed by civil rights groups, noted that the ruling’s impact would be to make it harder for the poor, people with disabilities and veterans to vote. While she did not say it, those constituencies tend not to support GOP candidates—such as those in Husted’s party.

“It is unsurprising in light of the history of such purge programs that numerous amici [groups filing briefs] report that the Supplemental Process has disproportionately affected minority, low-income, disabled, and veteran voters,” she said. “As one example, amici point to an investigation that revealed that in Hamilton County, ‘African-American-majority neighborhoods in downtown Cincinnati had 10% of their voters removed due to inactivity’ since 2012, as ‘compared to only 4% of voters in a suburban, majority-white neighborhood.’”

Sotomayor continued, “Amici [filers] also explain at length how low voter turnout rates, language-access problems, mail delivery issues, inflexible work schedules, and transportation issues, among other obstacles, make it more difficult for many minority, low-income, disabled, homeless, and veteran voters to cast a ballot or return a notice, rendering them particularly vulnerable to unwarranted removal under the Supplemental Process.”

Regional Impacts

The Court’s ruling was “a victory for election integrity,” Husted said, and was praised by President Trump in a tweet. But beyond the political rhetoric, the ruling underscores that there are two Americas when it comes to voting.

Blue-state America, as seen by responses on Twitter and other forums, said that the right to vote is sacred and universal and must be upheld. While that is a moral statement, it is not the current law in red states. Republicans are free to impose transactional barriers to the process—and keep doing so.

Ohio was not alone in arguing for aggressive purges. Fourteen states, led by Georgia, filed a brief defending Ohio’s purges. Some of these states have ongoing legal fights over registration barriers and limiting ballot access. (The states were: Alaska, Idaho, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas and West Virginia.)

This excerpt, summarizing the Republican attorneys general’s argument, illustrates how GOP office holders intentionally create processes to limit voter participation and then concoct legal arguments to defend it.

“Ohio’s list-maintenance process does not ‘result in’ (i.e., cause or produce) the removal of a person’s name from the official list of voters ‘by reason of ‘ (i.e., as a proximate cause of) that person’s failure to vote,” their brief said. “Removal is not, for instance, directly related to a person’s failure to vote, because it is more closely related to and purely contingent upon a person’s failure to respond to the address-confirmation notice sent as part of the Confirmation Procedure.”

Remarkably, Alito, writing for the majority, adopted that rationale. Looking ahead, one can expect Republicans in some of these states to try to ramp up voter purges this summer—as the NVRA bars removals 90 days before all federal elections.

Philip Bump, writing for the Washington Post, noted there are more infrequent Democratic voters in the 10 largest states than Republicans.

“Democrats outnumber Republicans in most large states, but they often vote less frequently,” he said. “The upshot is that both nationally and in the 10 largest states in the country, the ratio of Democrats to Republicans is larger among those at risk of being purged by an Ohio-style rule than among the overall voting pool.

Four of those 10 most-populous states are Texas, Michigan, Georgia and Ohio, which all took pro-purge stances before the Court. They are also states that would be politically purple, or trending purple, were it not for GOP-led legislation and regulations to make it harder to cast a ballot—like the “supplemental” procedure at issue in the Ohio litigation.

Despite 2018’s apparent blue voter turnout wave, the Supreme Court’s validation of Ohio’s aggressive purges is a stark reminder that in America, there are dueling partisan versions of who should and should not vote—cloaked in how arduous or friendly the process is.

It may be that Democratic voter turnout in November will rival 1974, the midterm after Richard Nixon resigned. But rulings like the Court’s Ohio voter purge decision will last for decades. And voter purges were not the biggest election law case before the current court term: hyperpartisan gerrymanders, or segregating likely voters by party, is up next.

Also Available on: www.alternet.org