Virginia Early Voting Disruption Highlights Varying Voter Intimidation Laws

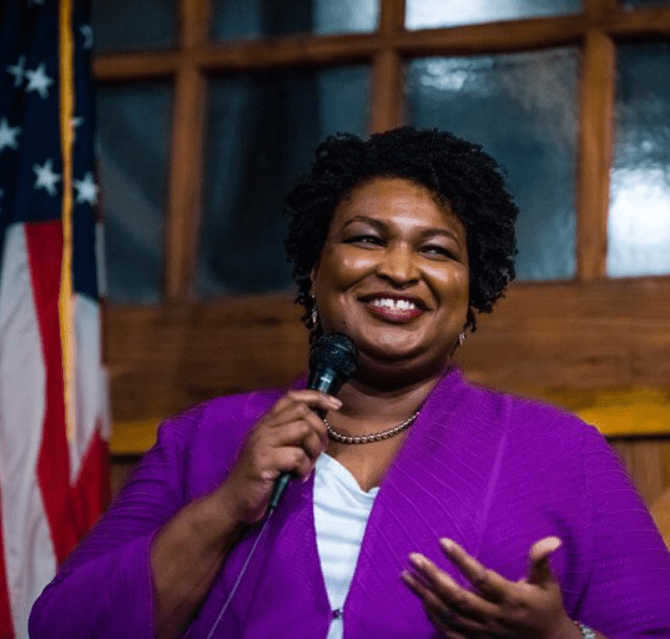

(Photo / twitter.com/Jonesnj)

The photo showed six mask-less Trump supporters waving Trump-Pence signs outside the entrance to Fairfax County Government Center on September 19, Virginia’s second day of early voting. The accompanying New York Times’ report describing their loud electioneering in the populous blue county outside Washington inflamed passions and went viral.

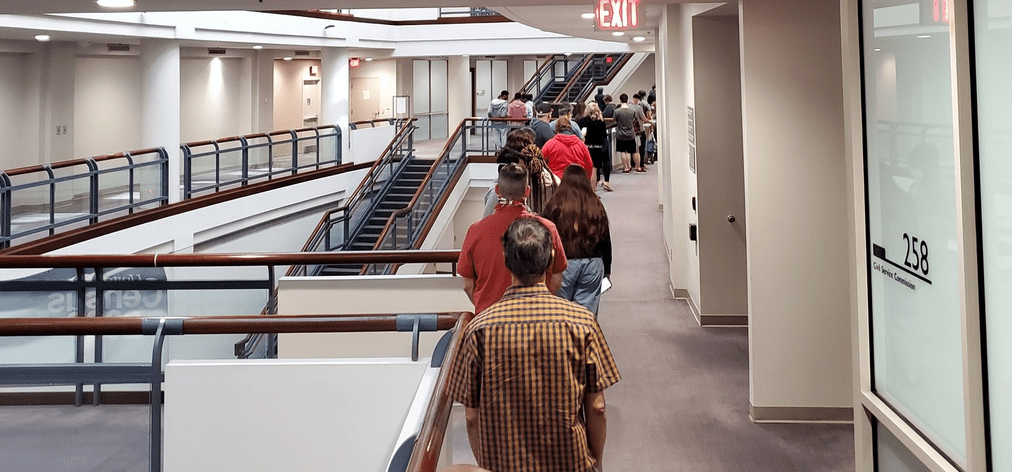

“No gang of goons is going to deter Fairfax from voting,” tweeted Nate Jones, an area resident, who noted that local officials moved the line inside the center, where people still had to wait several hours to vote, as it was the county’s only open early voting site.

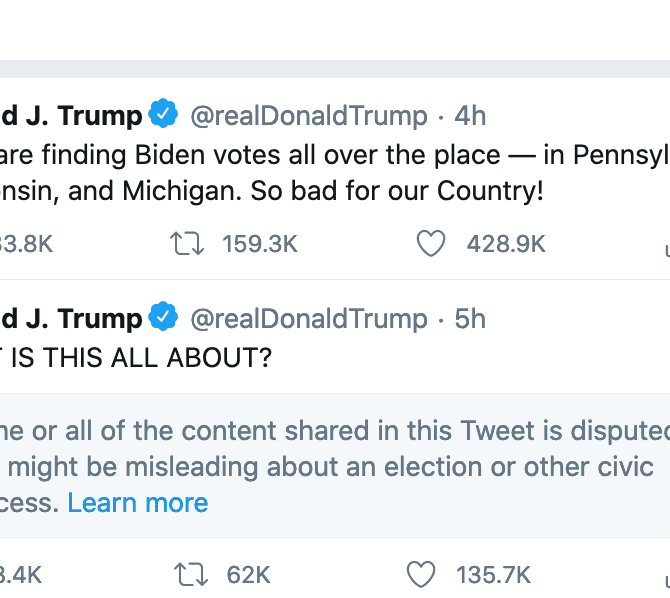

“Quick! Someone call the waaaambulance!” the Virginia Republican Party replied to a Times tweet that said, “Trump supporters disrupted the second day of early voting… chanting ‘four more years’ as voters entered a polling location. A county official said some voters and polling staff felt intimidated.”

Beyond the fears and jeers that broke along partisan lines—and questions about whether a predictable but noisy parade by Trump supporters deserved such attention—was the issue of whether the Trumpers’ unruly presence had broken any state or federal voter intimidation laws.

“What happened was they just came in revving truck and cars around the parking lot where there was this mile-long line that you have been seeing on the national news,” said Kristin Cabral, co-chair of the Fairfax County Democratic Party’s election law and voter protection committee, speaking on an activist call on Monday. “Then they got out of their cars with all sorts of banners and sticks and the like, not wearing face masks, and they gathered on the center plaza, which is basically where the front entrance, the front door, is.”

“They were creating such a ruckus,” she said. “This is the start of election interference, voter intimidation, that we can expect throughout early voting and on Election Day itself… The one thing that I was surprised, here in the open-carry state of Virginia, which is also the headquarters of the NRA, [was] that more folks did not have their weaponry on them.”

Cabral was hoping the county’s prosecutor, an elected Democrat, would file charges to send a message. Other non-Virginians on the call suggested that activists and election officials meet with local police “who don’t know anything about election law,” to be clear on what constitutes disturbing the peace and intimidating voters.

The episode was, at best, a cautionary tale, and, at worst, a portent for battleground states. Inviting a police presence to polls is dicey. What some people see as protecting voters may be seen by others as intimidating voters.

The law, too, has inconsistencies. While federal law is clear on what constitutes voter intimidation, state law primarily regulates elections and has widely varying standards. In some states, electioneering activity—anything that urges voters to support one candidate or cause—has to stop hundreds of feet away from polling place entrances. In other states, it can follow voters up to the doors or even go inside.

Federal law says that “whoever intimidates, threatens, coerces, or attempts to intimidate, threaten, or coerce, any other person for the purpose of interfering with the right of such other person to vote” can be fined or jailed up to a one year.

State law draws different lines. This chart, from the National Association of Secretaries of State, and updated as of January 2020, lists the varying distances that campaigners must stand from polls. Sometimes that distance is measured in feet from the entrance. Sometimes it is the distance from building’s perimeter. Sometimes it is how far a partisan campaigner must stand from a voter in a hallway.

Louisiana has the largest berth, “a radius of 600 feet from the entrance to any polling place.” In most states, that distance is 100 feet or more from the entrance. But there are exceptions in some 2020 battleground states.

In Virginia, electioneering has to stop “within 40 feet of any entrance.” Pennsylvania partisans “must remain at least (10) ten feet distant from the polling place.” North Carolina’s line is 50 feet from the entrance door and 25 feet from the rest of the building.

In Florida, Michigan, Minnesota, Nevada and Wisconsin, it’s 100 feet. In Georgia, it’s 150 feet. In Mississippi and Alabama, it’s 30 feet. In Missouri, it’s 25 feet. In Vermont, electioneering must stop at the entrance to a building. In New Hampshire, it can continue inside, but voters must be given “a corridor 10 feet wide.”

“I think what we have to do is meet with our boards of elections, meet with our mayors and city councils,” said Joel Segal, a former U.S. House Judiciary Committee legal staffer who lives in North Carolina, speaking on Monday’s activist call. “It is not unconstitutional to tell people that there’s a limit on your freedom of assembly. I don’t remember anything that said that could block the entrance for people voting.”

Also available on: AlterNet.