Virginia and Georgia, Southern Bastions, Take Opposite Courses on Voting Rights

(Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp. Photo by nlintheusa is licensed under CC BY 2.0)

As a mass shooting, possible tornadoes and school closures drew Georgians’ attention on St. Patrick’s Day, Republicans in its GOP-majority legislature in Atlanta raced to push a massive rewrite of an election bill to “drastically change” the state’s voting laws toward passage.

“HAPPENING NOW: Georgia House Republicans led by Rep. Barry Fleming are rushing out a 93-page substitute to SB 202 right before a key committee meeting to try and ram through their anti-voting agenda as part of their unconstitutional attacks on Georgians’ voting rights,” tweeted Fair Fight, an Atlanta-based voting rights group, on March 17.

“There are nearly 80 voting-related bills about voting+elections in Georgia. Most won’t go anywhere. Others keep changing faster than you can read them,” tweeted Stephen Fowler, Georgia Public Broadcasting’s reporter, echoing the alert.

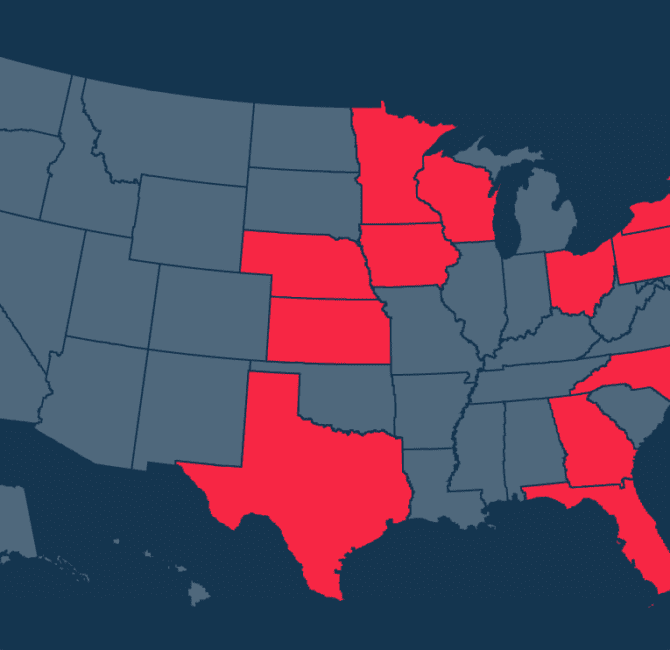

Such hardball tactics are not unique to Georgia’s legislature. Following 2020’s election loss, ex-President Trump’s supporters are using their power as lawmakers to try to change the rules of voting to their perceived benefit. In Georgia, currently the nation’s foremost swing state, the legislative melee also reflects fierce responses from voting rights advocates.

“They got more pushback than they expected,” said Andrea Miller, who runs the Center for Common Ground, which advocates for Black voters in the South and coordinated 3,700 phone calls from their districts to the Republican legislators sponsoring the rollbacks, and helped to shepherd 40,000 emails opposing the legislation.

Other groups have also pressed Georgia’s biggest employers to oppose the bills—and gained some traction. Some of the most draconian proposals, such as ending no-excuse absentee balloting, automatic voter registration and restricting early voting on Sunday—favored by Black clergy and congregations—are being withdrawn. Rep. Fleming was fired as Randolph County attorney for sponsoring suppressive legislation. But bills regulating voting keep hurtling forward.

“It’s such a moving target,” Miller said, speaking of the GOP’s tactics. “We are seeing every legislative trick in the book. A bill comes over from the Senate. You totally rewrite it in the morning and then have the hearing, the committee vote, that afternoon.”

Georgia’s voting war is one front line in the national battle over the options to get and cast a ballot. While many Georgia Republicans are reviving old fears about empowering their critics to vote, hold office and possibly make decisions affecting their lives, another key Southern state, Virginia, has taken the opposite course. Since 2020, Virginia Democrats have vastly expanded voting options and rights, embracing the state’s growing diversity and setting a different example.

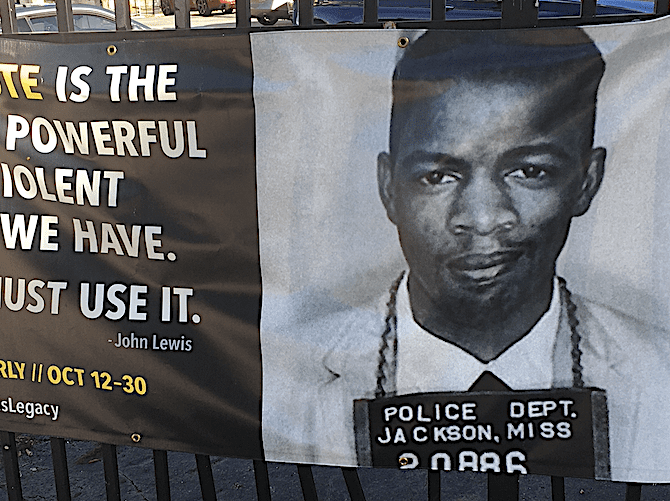

“Virginia’s work in 2021 is a model of voting rights expansion for states,” said Jorge Vasquez, power and democracy director for Advancement Project, a civil rights group. “Governor Ralph Northam’s [March 16] announcement [restoring voting rights to 69,000 ex-felons] is the capstone of a successful legislative session in which advocates successfully passed the Voting Rights Act of Virginia, the most expansive piece of voting rights legislation in the South.”

There may be no wider contrast between the politics and polarities surrounding voting rights at the start of the post-Trump era than between Georgia Republicans’ efforts to restrict voting and Virginia Democrats’ recent efforts to expand the franchise. Since the November 2019 statewide elections in Virginia—which returned a Democratic state legislative majority for the first time in 20 years—the state had adopted several waves of inclusionary reforms.

“Virginia is the gateway,” said Miller. “Virginia is the former capital of the Confederacy. So which direction does the South go? Does it follow Virginia? Or does it follow Georgia?”

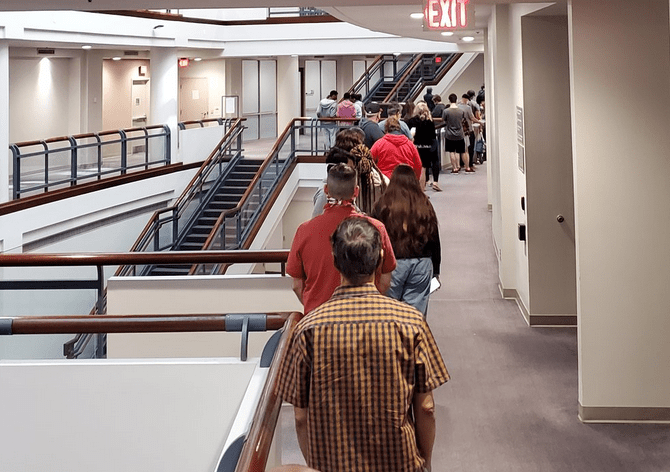

Virginia’s 2020 legislative session, which ended in February before the pandemic struck, passed a catalog of reforms. A longer no-excuse absentee voting period beginning 45 days before Election Day was instituted. The list of documents that would be accepted as voter ID was expanded. Election Day became a holiday. Automatic voter registration would be done at state motor vehicle offices unless residents opted out. A bipartisan redistricting commission was created for 2021. Same-day voter registration would begin in July 2022. It passed the federal Equal Rights Amendment.

In August 2020, a special session to address the pandemic further expanded voting options in Virginia. Registrars were required to contact voters to fix any mistakes they had made when filling out their ballot-return envelopes. A witness signature requirement for returned absentee ballot envelopes was suspended. Those envelopes had prepaid return postage. Drop boxes also were put into use to collect ballots.

“2020 was an incredible year where there were huge changes,” said Deb Wake, League of Women Voters of Virginia president. “Before the changes in voting laws, Virginia was… [ranked 49th in the list of states based on how easy it was to vote there]. After the 2020 legislative sessions, we moved to the 12th [easiest state in which to vote].”

In Virginia’s 2021 legislative session, which ended in February, most of the emergency responses to the pandemic were made permanent—except for suspending a witness signature on ballot return envelopes. Legislators also passed a state constitutional amendment to re-enfranchise ex-felons—a process that takes several years to enact. (It also abolished the death penalty, legalized recreational marijuana and allowed state health plans to cover abortions.) Gov. Northam is expected to sign all of these measures into law, advocates said.

A state Voting Rights Act was also passed. It bars the “denial or abridgment of the right of any United States citizen to vote based on his race or color or membership in a language minority group.” It notably also creates a process where any change in voting rules can be contested—and reversed—if it rolls back prior voting options. This preclearance is akin to what the U.S. Supreme Court removed from the federal Voting Rights Act in a 2013 decision—which led numerous Southern states to quickly enact new barriers for voters.

“With the preclearance requirement of federal law eliminated by the U.S. Supreme Court, Virginia replaced that rule with its own preclearance requirement,” wrote Janet Boyd in a March 1 legislative summary for the League of Women Voters of Virginia. “The preclearance rule provides two pathways for a locality to clear changes, either through a process of providing public notice and receiving comments or through approval by the Office of the Attorney General.”

“The legislature did flip from Republican to Democratic control in 2019, and that did allow for many of these voting/election laws to pass,” said Wake. “One of the things leading to the flip was the redrawing of racially gerrymandered [legislative districts]. … We now have our own VRA [Voting Rights Act], and we have a bipartisan, citizen-led redistricting commission. It’s not independent, but it’s a huge step forward.”

What Happened in Virginia?

Despite the inclusive voting rights legislation, Wake was “not prepared” to call Virginia a blue state. “I can attest that more people are engaged than were before 2016. I also note that the election/voting meetings since the November [2020] election have been full of new faces concerned about voter fraud—and all of their questions and objections fall on the incorrect assertion that there is massive voter fraud. Many people do not understand the system, and many people live in a partisan echo chamber. The challenge is to inform voters in a way that they hear, and [to] accept truths and processes that prevent the thing they fear.”

Wake’s prescription of informed engagement is precisely what led Virginia’s progressives—arguably more than its centrist Democrats—to start focusing on local politics after the 2016 defeat of Bernie Sanders in the presidential primaries, and the defeat of its U.S. senator and 2016 vice presidential nominee, Tim Kaine, in that year’s general election.

Miller, who lives near Richmond, said Virginia’s political landscape was similar to Georgia’s. “People tend to look at Georgia and look at their legislature and say, ‘Oh, there’s no point in trying to do anything in that state.’ Virginia looked exactly like Georgia five years ago.”

Virginia is among a handful of states with statewide elections in odd-numbered years. In 2015, the year before the presidential campaign that elected Trump, 61 out of 100 seats in its House of Delegates, its lower chamber, were uncontested. After Sanders’ and Hillary Clinton’s loss, many progressives, including men and women of color who never held elective office, decided to continue their activism by running for delegate or supporting candidates, said Josh Stanfield, who created a widely signed pledge not to take donations from the state’s biggest utility companies.

In November 2017, many candidates—including men and women of color who in 2021 are now running for governor, lieutenant governor and attorney general—were elected without the initial support of Virginia’s Democratic Party, Miller said. Many of the national groups that were active in 2016 refocused on the state’s legislative races in 2017, Stanfield said, which helped boost voter turnout.

“The majority of the increase in voter turnout was anti-Trump backlash,” Stanfield said, “but what do we mean by anti-Trump backlash? It could include people who were fed up with xenophobia. It was not necessarily Trump-specific… There was so much more mobilization and organization on the ground. Among the grassroots activists, so many more people were involved.”

After the November 2017 election, partisan control of the 100-seat House of Delegates came down to a tie in one contest. On January 4, 2018, a Republican was declared the winner of that race—giving the GOP a 51-49 majority—after the state election board’s chair drew a slip of paper out of a bowl.

One year later, federal judges approved a court-ordered redrawing of 26 House of Delegate districts before Virginia’s 2019 elections, after a federal judge found that the Republican majority had used race-based considerations when drawing the districts’ boundaries after the 2010 census. In November 2019, 70 House of Delegate seats were contested. Democrats won a 55-45 seat majority. Democrats also won a 21-18 seat majority in the state’s Senate. (One seat is vacant.)

“One of the things leading to the flip in the legislature in 2019 was the redrawing of racially gerrymandered maps,” said Wake. “Besides the party flip—and more importantly—we see increased representation of minorities in Virginia. More women and more Black people are serving as legislators. Some legislators have served time. One is transgender. Some are Muslim. This means better representation, and we see this in the laws being passed.”

Virginia’s expansion of voting options and redrawing 26 lower legislative districts to be more representative have also led to the most diverse pool of Democratic and Republican candidates for governor, lieutenant governor and attorney general in upcoming party primaries and nominating conventions. There are more women, people of color, and religiously diverse candidates than in any prior election.

“The state’s Democratic gubernatorial primary, taking place in June, features the most diverse set of candidates in Virginia’s history,” noted Jewish Insider. “There’s Jennifer Carroll Foy, one of the first Black women to graduate from the esteemed Virginia Military Institute; Jennifer McClellan, a corporate attorney and vice chair of the Virginia Legislative Black Caucus; Justin Fairfax, the current lieutenant governor and just the second Black politician ever elected to statewide office; Lee Carter, a 33-year-old self-proclaimed socialist in the House of Delegates; and Terry McAuliffe, who served as governor once before and has been a Democratic Party fixture since the Clinton administration.”

“Virginia has four Black candidates running for governor in 2021. Who saw that coming in 2015?” Miller said. “Maybe the people of Georgia can look at Virginia and say, ‘Oh my. Maybe there’s hope for us. Virginia did it. Why can’t we?’ And Georgia has a bigger community of color population than Virginia—much bigger.”