Assessing the Moment: How Far Will Democrats Go for Democracy Reform?

(Photo by Sue Dorfman / Zuma Press)

On March 25, the day President Joe Biden held his first press conference and called bids by Republican state legislators to complicate voting “un-American,” Georgia’s legislature passed, and its Republican governor signed, 2021’s most aggressive rewrite of voting rules. That same day in Texas’ state legislature, a hearing was abruptly halted on a bill with arguably even more obstructive and punitive provisions before the chairs of its Black and Mexican American legislative caucuses were allowed to participate.

The Texas bill’s author and Texas House Elections Committee chair, Rep. Briscoe Cain, a Houston-area Republican, apparently made a procedural mistake—the kind of technicality contained in his bill that would criminalize election officials, poll workers or neighbors who did not precisely follow the bill’s new restrictions for absentee voting and its expanded rights for political party observers. The bill barred election officials from removing intentionally unruly partisans.

“This package of bills, along with many others being considered in the Texas House, could have the greatest impact on voting rights since the Jim Crow era,” said Charlie Bonner, spokesman for MOVE Texas, a nonprofit championing voting rights for young adults, at a Zoom briefing after the hearing’s halt. “Unlike Chair Cain, we don’t seek to criminalize those simple mistakes that often happen and will put many people, particularly Black and Brown voters, in jail.”

The interruption didn’t stop the Texas bill. Another public hearing took place on April 1. As in Georgia and other battleground states—Arizona, Florida, Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania—bills to curtail voting options and add unnecessary bureaucracy for election officials are moving through statehouses. But their momentum is having an opposite effect in the nation’s capital; it is underscoring a moral imperative and political will among almost all Democrats to pass history-making election and voting reform.

“It is an apocryphal moment, one of those like [before] the 1964 Civil Rights Act, one of those moments where you just feel the change gathering in Washington, in addition to analyzing it,” said Norman Eisen, a longtime anti-corruption policy analyst who led a Brookings Institution briefing on Senate Bill 1—the Democrats’ reform package—on the day of its first hearing in late March.

Revising election laws after presidential cycles is not new. And it’s not the first time each party has tried to do so where it holds legislative majorities. But the GOP push in state legislatures since January is outsized in volume and intensity. Very few of these proposals have been endorsed by the officials who administer elections, whether Democrat or Republican, said David Becker, executive director for the Center for Election Innovation and Research. (In 2020, the center disbursed $64 million in grants to these state officials from Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan.)

Most unwanted and meddlesome bills are coming from Republican state legislators who, along with some of their constituents, did not like the 2020 presidential election’s result, Becker said. Meanwhile, the response from voting rights advocates and Democrats has been as strident.

Georgia’s Democratic Party, like the Texas advocates, compared the pernicious aspects of its newest voting law, Senate Bill 202, to the Jim Crow era—which began in the 1890s and lasted through the 1960s across the South. Under Jim Crow, the governing class, including that era’s Democratic Party, unapologetically opposed empowering Black people, especially at the starting line for political representation—voter registration.

“This is a sad day for Georgia,” said Congresswoman Nikema Williams, Georgia Democratic Party chair. “Senate Bill 202—the most flagrantly racist, partisan power grab of elections in modern Georgia history—is a slap in the face to Georgia’s civil rights legacy. After losing elections because more voters of color made their voices heard, [Gov.] Brian Kemp and the GOP are now trying to outright silence Georgia voters by making it harder to cast a ballot and letting partisan actors take over local elections.”

The same point was made about the early Republican opposition to Senate Bill 1. The massive bill is a compendium of two dozen separate voting rights, election administration, campaign finance and ethics reform proposals dating to 2007. (Democrats would have to revise the Senate’s filibuster rule—ending debate—to pass it. Not all Democrats are on board with that strategy.) In the bill’s opening hearing in the Senate Rules Committee, several Republicans recited ex-President Trump’s lies about widespread Democratic voter fraud and said S. 1 would sully the purity of the ballot.

“If we actually compare what some people [like Texas Sen. Ted Cruz] are saying in the Senate to what we heard six or seven decades ago, where we would see people aiming to block civil rights legislation, it is very reminiscent,” said Rashawn Ray, a Brookings fellow and University of Maryland professor who has studied racial and social inequities, including police brutality. “When we really think about how it relates to the Jim Crow South, we can go back to the 1950s.”

“This is how much people actually don’t want to see people being able to vote,” Ray said. “We have to be very honest. Oftentimes, they don’t want to see people of color vote. They oftentimes don’t want to see immigrants vote—even people who are legal citizens. We really have to get down to the crux of what is going on. Through all of the noise, that was what I heard in the Senate. That unfortunately, some people, some of our elected officials, don’t actually want to see some people really be able to express and embrace what it means to be American.”

“What it means to be American” was at the heart of the Jim Crow era. For the ruling class, it meant white supremacy. As historian V.O. Key Jr. explained in his 1949 book based on hundreds of interviews, Southern Politics in State and Nation, these Southerners—politicians, judges, police, businessmen, editorial writers—did not want Black people to have power to make decisions affecting white people. Key called this effort a “disenfranchisement movement.”

But is it apt to compare the Republicans’ latest state-based moves to the Jim Crow era? Or is a more accurate parallel the GOP’s more recent efforts to overly regulate voting with “surgical precision,” as a federal appeals court put it in 2016 when describing suppressive laws that were quickly enacted in North Carolina after the Supreme Court in 2013 gutted the main enforcement tool of the Voting Rights Act of 1965? Morally, there may not be much difference. But politically and legally, it may matter quite a bit when considering the congressional and executive branch responses in 2021.

“Broadly considered, H.R. 1/S. 1 is a very sweeping election reform bill… They set out a floor, a set of rules that apply to all states for federal elections,” said Becker. “Section 5 [of the Voting Rights Act] is a very targeted tool. It is a scalpel. I say this as someone who has enforced Section 5 for many years as a Justice Department lawyer. It is one of the most effective tools in the toolbox of voting rights enforcement that this nation has ever seen.”

“That’s because it is targeted only at those states that have a history of voter discrimination, and it requires those states to affirmatively request approval for any change [in voting laws or rules] before it can be implemented,” he explained. “This means that the law enforcers don’t have to go looking for violations. The state, or whatever smaller jurisdiction or county, has to send those [changes] directly to the Department of Justice, and they cannot implement them until they have been pre-cleared… It is not something that necessarily applies to everybody.”

Already, some constitutional scholars are arguing that restoring the Voting Rights Act could counter the most regressive laws coming from state legislatures. The John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act could do this, they suggest, but that 2019 bill has not yet been introduced in the current Congress. Democrats, for now, are focusing on S. 1, the more sweeping bill.

The Early 1960s Versus Today

When President Lyndon Johnson, the first Southern president in decades, finally saw the need for voting rights legislation, he told his attorney general designee, “I want you to write me the goddamnest toughest voting rights act that you can devise.”

The heart of that bill, which became the Voting Rights Act of 1965, was the act’s Section 5 and enforcement formula in Section 4(b). In 2013, the Supreme Court, in a ruling written by Chief Justice John Roberts, threw out the VRA’s pre-clearance formula. “There is no denying,” the decision said, “that the conditions that originally justified these measures no longer characterize voting in the covered jurisdictions.”

Many books detail, in excruciating fashion, the violence surrounding that era’s voting rights struggle. Local police, long before they dressed in leftover military gear as today, brandished cruder weapons against unarmed men, women and children. Protesters were chased, beaten, fire-hosed and tear-gassed. Bystanders were targeted. People were shot and killed. When charges were pressed, the victims were accused of assaulting the police. Because juries were drawn from rolls of registered voters, cases ended up before all-white juries.

The 1960s voting rights protests focused on the starting line of the democratic political process, voter registration. Since the 1890s, when Jim Crow began with the imposition of poll taxes and literacy tests (and exceptions for white people) blocking Black voter registration was seen, correctly, as the glue holding the South’s political system together. The half-dozen years before and after the turn of the century saw the Supreme Court uphold segregation (Plessy v. Ferguson) and Mississippi and Alabama laws that disenfranchised Black voters. Over a decade, hundreds of thousands of Black Americans were cut from voter rolls, a status quo that lasted until the mid-1960s.

The federal government, led by presidents who did not want to interfere, was largely hands off until the mid-1950s. Dwight Eisenhower, the World War II commanding general whose military was integrated and who was president from 1953 to 1961, pushed for a civil rights bill. Early in his presidency, the Supreme Court ordered the integration of public schools in Brown v. Board of Education. But desegregating schools did not lead to Black citizens gaining political power, as the New Yorker’s Louis Menand noted in an article that profiled the voting rights legacy that was undermined by the Supreme Court’s Shelby v. Holder ruling in 2013. Eisenhower’s legislation, which was a watered-down bill, passed in as the 1957 Civil Rights Act. Still, it was the first civil rights law passed since the Reconstruction era after the Civil War, which temporarily enfranchised Black Americans.

But the 1957 Act could not break Jim Crow’s hold. While it allowed the Justice Department “to pursue litigation against local registrars who discriminated on the basis of race,” Menand noted that the case law precedents at that time required prosecutors to prove intent—what was in the mind of those local officials accused of discrimination. That task was nearly impossible. It was not until after President John F. Kennedy’s assassination in late 1963, when President Lyndon B. Johnson took up the dead president’s civil rights bill, that the need for a voting rights bill emerged. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 banned segregation in public—hotels, restaurants, movie theaters and government offices. It passed after the longest filibuster in Senate history. But it, too, did not prevent Jim Crow tools like literacy tests for voters.

When Johnson told Nicholas Katzenbach to draft the “goddamnest toughest voting rights act,” his attorney general designee came up with the pre-clearance regime. The covered states, counties and cities, meaning those with histories of racial discrimination in voting, had to gain Justice Department approval before implementing new voting laws or rules. Federal prosecutors no longer had to prove that it was the intent of officials and laws to intentionally disenfranchise. The government could look at the effect of any law, and, as Becker noted from his days as a DOJ Voting Section attorney a dozen years ago, covered jurisdictions had to proactively get approval from the Justice Department.

“The 1965 Voting Rights Act was the most successful piece of civil rights legislation our country has ever seen,” said Mimi Marziani, the Texas Civil Rights Project president. “It completely changed who has a seat at the table.”

Voting Rights Crossroads

There are important differences between the political and cultural landscape of today and the landscape of the early 1960s through the passage of the Voting Rights Act in August 1965. The violence surrounding integration, which predated the 1964 Civil Rights Act, became a national disgrace. In 1960, the country saw Black students in Greensboro, South Carolina—students from the state’s largest all-Black university—mocked and attacked as they sat at a “whites-only” downtown lunch counter. As the disobedience deepened, the violence worsened.

Activists who went south to help with voter registration drives were brutalized and killed. Reporters, photographers and TV crews brought stories and images of the violence to the front pages and TV screens across America and internationally. By the end of the summer of 1964 in Mississippi, 35 churches and 30 other buildings had been firebombed. In that November’s presidential election, five deep South states flipped from solidly Democratic to solidly Republican. But Johnson won in a national landslide.

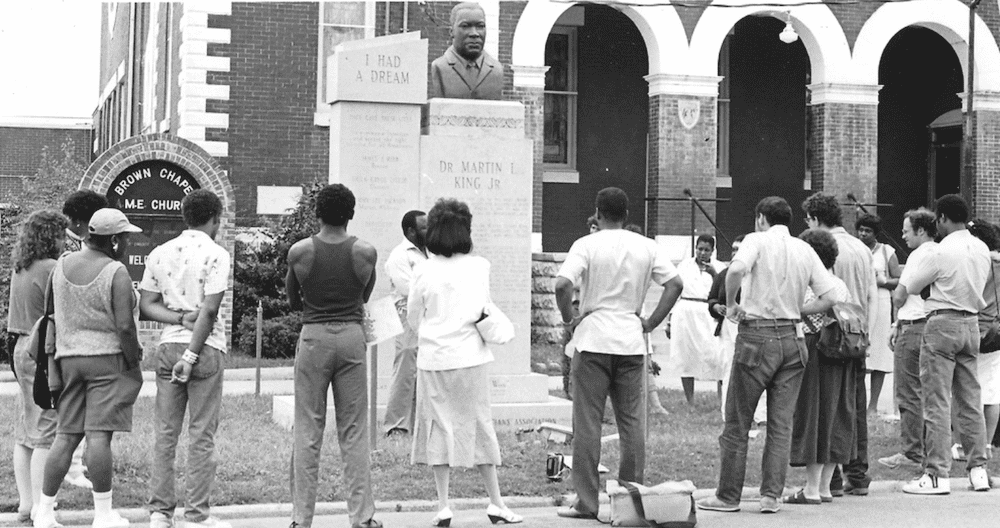

Johnson’s first elected term as president was a time of deepening upheaval. He escalated troop deployments to Vietnam. Civil rights leaders were told it was not time for voting rights reform. Like all protest movements, there were competing factions. On March 7, 1965, John Lewis and Hosea Williams led a march from a chapel in Selma, Alabama, toward the Edmund Pettus Bridge—named for a Confederate general and Ku Klux Klan leader—on the outskirts of the city. They planned to march to Montgomery, Alabama’s capital, but they were met by a sheriff-led posse on horseback whose leader had been told by Alabama Gov. George Wallace to take “whatever steps necessary” to stop them. Like a 1920s lynching, many white people came out to watch.

ABC television crews were there. That night, the network broke into a movie on Nazi war crimes and broadcast 15 minutes of raw footage of police attack, tear gassing, beatings, yelling and screaming to 48 million viewers. Historians say that President Johnson knew that he could not win a Cold War abroad if he could not defeat anti-democratic institutions at home. By the time Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act that August, he surely knew that most of the South was lost to Republicans. But political machinations aside, Johnson put country before party, which no Republican in Congress seems willing to do in 2021 for voting rights and fairer elections.

There are other differences between the early 1960s voting rights struggles and today. In 2021, images of institutional racism—such as the video of George Floyd’s killing by a police officer in Minneapolis—rocket around the nation and world in minutes. The protesters in the Black Lives Matter movement are not timid. They seek a deeper reckoning than merely cracking open the door that blocked Black Americans’ path to political power in the 1960s: voter registration. Less than one week after Georgia’s Gov. Kemp signed Senate Bill 202 into law, protesters pushed two of the state’s largest corporations—Delta Air Lines and Coca-Cola—to speak out in opposition to the law. Georgia-based voting rights advocates had called for boycotts, a tactic echoing the early 1960s, when businesses across the South learned that losing Black customers was not a good business strategy.

In the early 1960s and early 2020s, the moral case for voting rights and more representative government has similar echoes. But the fine print of each era’s obstacles is different, as are the potential solutions. “It’s actually hard to compare today to 1965,” said Richard Pildes, a New York University election and constitutional law scholar. “Because people too easily forget what that world looked like when something like only 6 percent of Black voters in Mississippi were even registered to vote, when there was economic retaliation against Black voters who sought to register, when the national government had largely been absent from the field since 1890. And now we are in a world in which Black turnout rates are higher than white ones in some states.”

What is the best response to the Republican Party’s recent efforts to narrow the options to get a ballot into a voter’s hands in swing states and to add unneeded complexities for election workers before counting ballots? Is it passing major federal legislation comprised of democracy reforms that have been called for by Democrats for years? Is it reviving and updating the most successful civil rights tool ever passed, the VRA’s pre-clearance, for this century? Is it some combination of the two?

Those on the front lines of battles for more representative government, like Texas’ Marziani, quickly said today’s demons are the technocratic rules that have ushered forth following the Supreme Court’s gutting of the VRA in its 2013 Shelby County v. Holder ruling. Yesteryear’s club-wielding sheriffs have been replaced by partisans who boast of upholding the purity of elections while pushing provisions targeting voting blocs. They are, as V.O. Key put it 1949, the “disenfranchisement movement.”

“What we have been battling in the past 10 years, facilitated… by the Supreme Court and its chipping away at the Voting Rights Act, has been a new effort to pass what at times are called ‘second-generation’ restrictions on voting,” Marziani said. “They are more subtle, I would say, than what we saw in the ’50s and the ’60s. They tend to be—one of the legal words is facially neutral—so they are not actually saying that they are discriminating, although I have to say that parts of these [2021] bills are probably not facially neutral.”

But Marziani also said that there was an emotional and moral charge to today’s voting rights battles that have been with the county since its founding—the slow arc of the progress over how inclusionary or exclusionary voting and government would be.

“I think there is an apt analogy; that kind of fundamental struggle against a changing electorate, using the election rules to try to keep yourself in power, is a very similar thing to what we’ve seen, honestly, several times in America’s history.”

The country faced a reckoning with electoral representation in the early 1960s. It did not end white supremacy. Nor did it fully empower Black people across the South, although the political and economic gains of recent decades are undeniable. Today, in the early 2020s, another voting rights reckoning is in the air in Washington.

This past March 7, 56 years after the “Bloody Sunday” march in Selma, President Biden signed an executive order to “increase access to voter registration services and information about voting” at federal agencies. The White House press office called the order “an initial step.” It said, “The President is committed to working with Congress to restore the Voting Rights Act and pass H.R. 1, the For the People Act, which includes bold reforms to make it more equitable and accessible for all Americans to exercise their fundamental right to vote.” As was the case in 1965, the open question is how forceful Democrats, including the president, will be.