How a Hurricane-Hit Florida County Shored Up Its Voting System

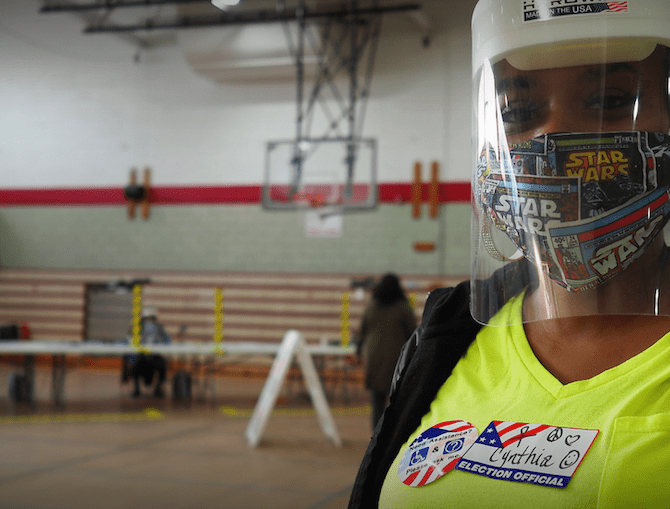

(Photo / Steven Rosenfeld)

All of America’s political convulsions and contradictions are present in 2018’s midterms—including attacks on voting itself.

In the last 48 hours, President Donald Trump and Attorney General Jeff Sessions reissued threats to crack down on illegal voting by non-citizens, which rarely occurs. That followed the GOP’s most controversial gubernatorial candidate, Georgia Secretary of State Brian Kemp, accusing his state’s Democratic Party of hacking into voter rolls—which they ridiculed—and then tweeting that armed blacks were supporting his opponent.

Across the aisle, Democrats and voting advocates have criticized these tactics and publicized other barriers, fighting the worst in court and trying to help individuals in affected states get a ballot. Meanwhile, as Tuesday unfolds, the press is detailing problems in key states like Georgia, creating lines to vote lasting hours.

These gyrations are part of a larger canvas where both sides see “cataclysmic scenarios,” as Lawrence Jacobs, a University of Minnesota political scientist, put it to USA Today. In most of America, however, voting has not collapsed. High participation rates, as seen by the percentages of people voting early, continued on Tuesday.

And in one slice of the country where the sky did fall, the economy was wrecked and daily life has become truly nightmarish—in Florida’s hurricane-devastated region around Panama City—election officials are not just up and running, and handling record turnout; they are operating one of the country’s most transparent and secure voting systems. In contrast to much of America, they can ensure every ballot will be counted in a manner with virtually no possibility outsiders can hack the results.

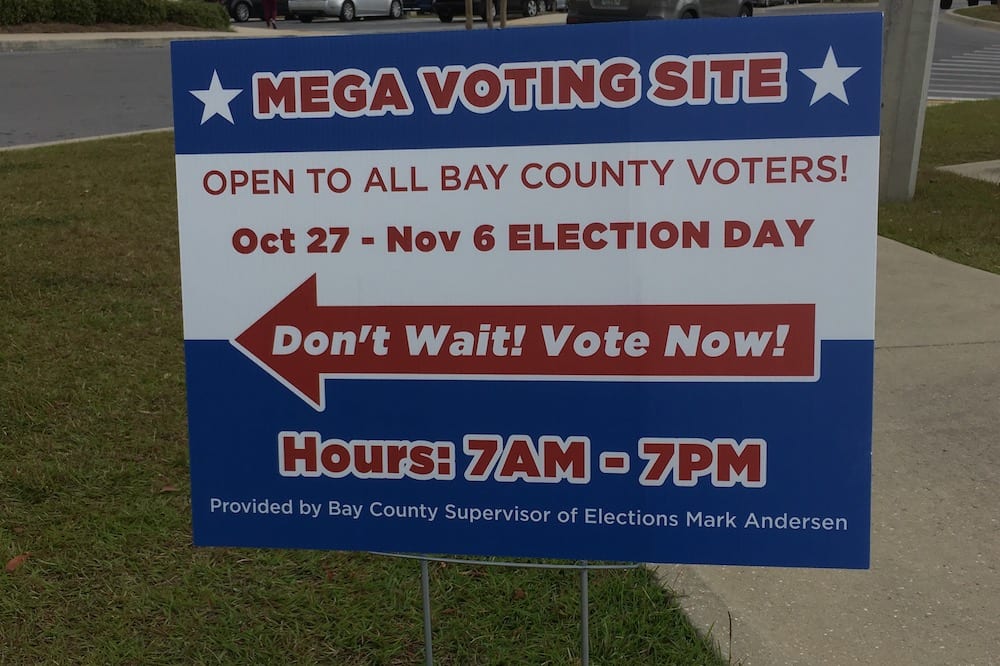

“We know we can get a voter checked in in one minute or less, a ballot printed in less than 30 or 40 seconds, and they’re off in the voting booth,” said Mark Andersen, Bay County Supervisor of Elections, describing the start of a meticulous process that he’s staging in a half-dozen “mega voting” sites, all buildings where power was restored.

Andersen was talking in his office inside Bay County’s government center, a sturdy tan brick building next to a school torn apart to its steel beams and homes encircled by mounds of tree debris and ruined possessions. This voting center was in a back storeroom where power had been restored and air conditioning set up to help keep moisture from interfering with the paper ballot processing. Any registered voter in the county could show up and vote there.

As the morning progressed, voters trickled in and out and seemed satisfied, not even knowing that they were walking past a secure room where their ballots and votes would be verified late on Tuesday and early Wednesday to ensure no extra ballots were used, and that every vote cast in every race was accounted for.

“We’ve been busy all morning. We’ve had lines,” said a volunteer manning the front door who said he shouldn’t give his name—a retired county election official. “A lot of people are not working; they have time on their hands and this is right in front of them. With all the news in your face, they figure they can do something about it.”

The system used in Bay County was developed by Andersen and a handful of his peers, notably Leon County’s Mark Earley and Ion Sancho. It comes down to this: paper ballots are printed for voters as they check in, which means at the end of every day of voting early and on Election Day, officials can ensure that the total number of ballots given out, marked and securely collected is the same as the number of voters. That means no illegal voters or ballot box stuffing.

Then the paper ballots are scanned by two separate computer systems that never touch. That gap—only bridged by the paper ballot itself—means there is no way for an outsider or electronic interloper to sabotage the vote-counting electronics.

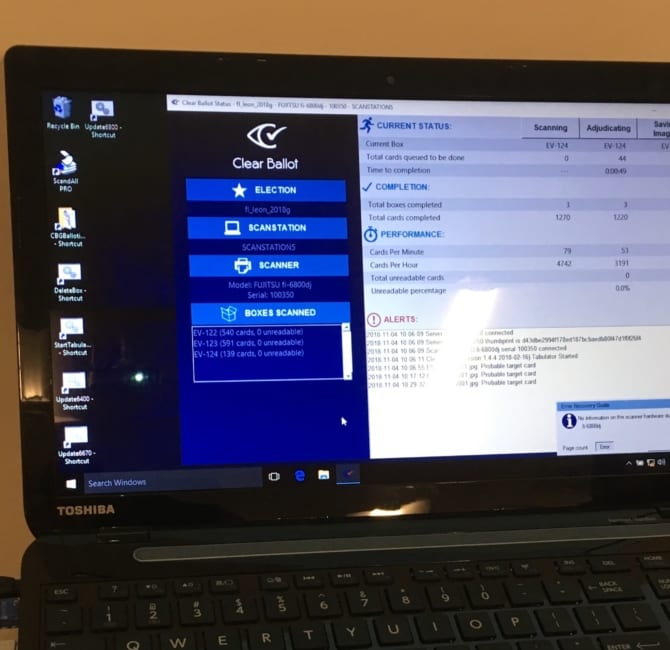

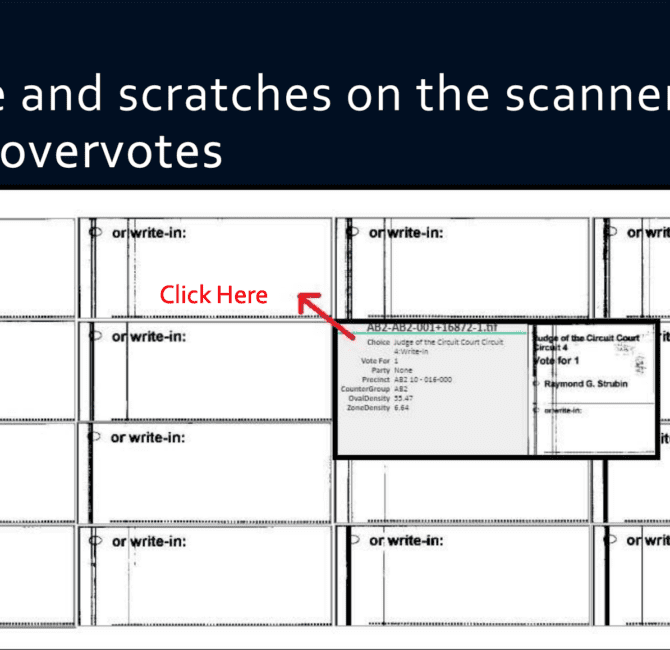

The first system, in voting centers like Panama City’s ‘mega’ vote center or a local precinct, counts the day’s results. It makes an image of every ballot card scanned and adds up every contest. Then those ballots are returned to secured settings, where they are run through a second scanner creating high-definition images of every ballot, which are used to analyze every marked ballot oval. That system generates two separate totals from the same ballots that can be compared.

If there are discrepancies between computer systems, and sometimes there are, the inventory created by the second scan can trace discrepancies down to the precinct level (actually to the voting machine used) and then allows for a fast retrieval of individual paper ballots in question. That process—of two separate scanners, and paper ballots put into a well-indexed system—is transparent and trustable.

“I review every single ballot,” Andersen said. “I can tell my voters I audit the entire election and I do. [There’s] an independent counting system, an independent audit system, and no files cross. Only the paper [is in common]. I dare you to find anything better … it’s that simple.”

Outside the entrance to the county building, local residents praised the process.

“It’s very important to vote today, because this will make a heck of a lot of difference, and I do believe in change,” said Clara Mincy, a retired educator and now a school bus driver. “A change is gonna come,” said Betty McCray, standing next to her.

When asked if she trusted that her vote would be counted, Mincy said yes.

“I do. Because I think it has been done correct,” she said. “We haven’t had problems like down south. I remember a few problems down south. But I haven’t heard of any in northwest Florida. That’s why I have confidence.”

Also Available on: www.truthdig.com