Voter Data Suppression Is GOP’s Latest Anti-Voter Tactic

(Photo / Steven Rosenfeld)

As early voting has begun across America and seen record turnouts, the big question is: Will people voting for Democrats surmount the obstacles that the GOP has built in red-run states to achieve winning popular vote majorities?

Those obstacles began with extreme gerrymanders in 2011 for state legislative and U.S. House districts. They continued with newly crafted red super-majorities passing strict voter ID laws. And now, in the finale to 2018’s midterms, a new tactic is emerging that can be described as data suppression.

In short, in a handful of red-run states with change-making races, voter information that would normally add people to registration rolls is not being readily processed. That scenario creates a likely prospect of Election Day ambushes, starting with surprised people whose names are not in poll books, and then rippling outward as they fill out provisional ballots while others are delayed in line.

Versions of this voter data suppression gambit can be found in Arizona, Missouri and Georgia. These states have tight federal races—and in Georgia, one of the most-watched gubernatorial contests. In all of these red-run states, registration information affecting enough voters to possibly swing outcomes has become stuck in opaque bureaucratic pipelines.

Let’s look at these states and two others where voter information-driven tactics have surfaced—North Carolina and North Dakota.

Arizona

The state has 3.6 million voters, with 150,000 more registered Republicans than Democrats, according to the latest figures. It has competitive House races and a tight Senate race, where the polling average from RealClearPolitics.com places Democrat Kyrsten Sinema 0.3 percent ahead of Republican Martha McSally. If half of Arizona’s registered voters end up casting a ballot in November—a reasonable estimate in what’s forecast to be a record year—that means every 18,000 votes are 1 percent of the popular vote. That scenario translates into about a 5,400-vote lead by Sinema.

What’s Arizona’s data suppression ploy? Its motor vehicle agency is not forwarding change of addresses for 384,000 people getting driver’s licenses to the state’s voter registration database. Of that figure, 63,000 are people who apparently moved to a new county, meaning they have to completely re-register to vote.

It’s a safe bet that a sizable number of affected individuals have no idea what’s going on—and won’t until they try to vote. Voting rights groups sued to force this red-run state to update its statewide voter database. A federal judge sided with Arizona officials (who said they will fix this problem in 2019). Nonetheless, Arizona’s intransigence is a perfect example where barriers surrounding vetting voter data will impact and shape its 2018 electorate.

Missouri

A counterpoint to what’s unfolding in Arizona can be found in this state of roughly 4.5 million voters. Here, too, if midterm turnout is half of that electorate, then every 22,500 votes equates to 1 percent of the popular vote. In Missouri’s very tight Senate race, RealClearPolitics’ poll average has Republican challenger Josh Hawley ahead of the incumbent Democrat, Claire McCaskill, by 0.4 percent, which is approximately a 10,000-vote lead.

What is Missouri’s data suppression ploy? It’s like Arizona, and involves updated information on 200,000 voters submitted to that state’s motor vehicle agency. Notably, a federal judge this month ordered Missouri to deliver that information to election officials. Whether it will do so in time (in a manner that doesn’t impede big numbers of 2018 voters) remains to be seen—despite what looks like a victory for voting rights advocates. That skeptical take is because big state bureaucracies are not exactly speedy.

How all this plays out will not really be known until Election Day because Missouri only has limited early voting options, where tell-tale signs of snafus would first appear. Similarly, pro-voting rights litigators this week won another court ruling by overturning some elements of the state’s new and stricter voter ID law. But the late date of that ruling has led some election officials to say it will likely cause poll worker confusion, leading to voting delays.

Once again, hurdles surrounding the vetting of voter information may impede participation in close contests on Election Day.

Georgia

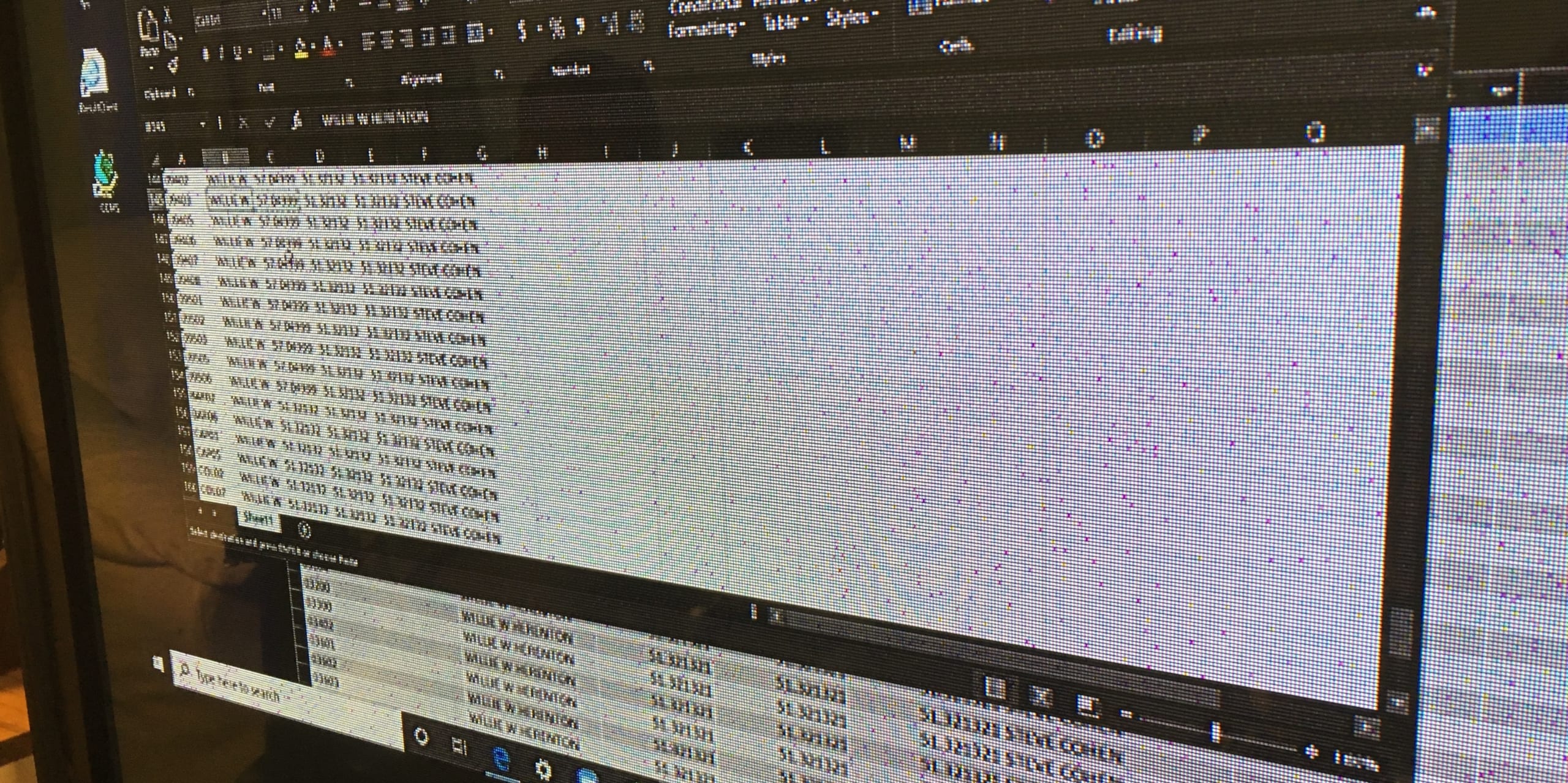

The governor’s race in this state of 6.9 million voters is a microcosm of this past decade’s partisan voting wars. The Republican, Secretary of State Brian Kemp, has a national reputation for aggressively purging voters, and for delaying the processing of registrations from new voters. This is especially true for the tens of thousands of voter applications submitted through a non-profit created by the Democratic contender in the governor’s race, ex-House Minority Leader Stacey Abrams. RealClearPolitics’ poll average has Kemp leading Abrams by 2 percent, which, if the midterm turnout is 50 percent, equates to about 70,000 votes.

In recent days, there has been a stream of credible reports showing Kemp is holding tens of thousands of recent registrations hostage. This is more data suppression, if you will, by not validating what’s submitted by eligible voters in a timely manner. Moreover, local officials, following a similar verification playbook, have been rejecting hundreds of early ballots in at least one non-white county. In both instances, voting rights groups have sued Georgia officials.

The big picture here is a schizophrenic voting rights tug-of-war. On one side is a state with record numbers of new voters. That is due in part to a GOP-run legislature instituting online registration several years ago and automatic voter registration in late 2016 for anyone getting a driver’s license. On one hand, 1.4 million voters have registered since November 2016. Yet on the other, Kemp’s watch has purged hundreds of thousands of registrations (668,000 last year), leaving about 250,000 new voters for 2018’s midterms, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported. Amid this mix of new voters are tens of thousands via the New Georgia Project, a voter drive launched by Abrams several years ago.

The common thread in these developments is a willful delay, if not mangling or rejection, of timely voter information.

Voting rights groups have sued Kemp (in his official capacity managing the election he’s running in) over the 53,000 pending registrations. They also have sued Kemp and Gwinnett County for rejecting 8.5 percent of early absentee ballots, where, again, a voter verification process has become a pathway to suppress turnout of an opponent’s likely base. Of the pending registrations, attorneys have noted in their complaint that less than 10 percent are white. (Kemp is white; Abrams is black.) The Journal-Constitution said that less than 40 percent of Gwinnett County voters are white.

And yet another eyebrow-raising example came in early October, when, two business days before the 2018 registration deadline, the computer system running Georgia’s online registration crashed, prompting the state to extend registration by two days.

Needless to say, these snafus and obstructions do not have to be part of the voting landscape—and in many blue-run states are not. It remains to be seen what will unfold in Georgia, but you can be sure that 2018’s voter suppression narrative is not finished.

North Dakota and North Carolina

Two more states are noteworthy with voter-information plays that are intended by the GOP to preserve or gain their power.

The first is North Carolina, where the Justice Department, acting on behalf of ICE—federal immigration authorities—sought access to every government record for registered voters (including driver’s license data) since 2010 in 44 counties in the most heavily Latino region of the state. After an outcry, the DOJ backed off and said it would seek the voter files in 2019. However, as former state Board of Elections senior officials said, the DOJ has signaled that it may investigate Latino families whose members dare to vote.

The second example is from North Dakota, where there is no state voter registration requirement and where 344,360 people voted in the 2016 presidential election. In its U.S. Senate race, Republican Kevin Cramer has an 8.7 percent lead over Democratic incumbent Heidi Heitkamp, according to RealClearPolitics’ polling average. If two-thirds of those 2016 presidential voters turn out in several weeks, that equates to 2,300 votes for every percentage point—giving Cramer roughly a 20,000-vote lead.

Last week, a GOP-appointed majority on the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear a challenge to North Dakota’s new voter ID law—which requires residents to present an ID with a street address to get a regular ballot. As a dissent by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg noted, “approximately 18,000 North Dakota residents” lack that form of ID. She was mostly referring to Native Americans who live on reservations and support Democrats. In other words, the Court refused to block a restrictive measure that, were it not in place, would make the state’s Senate race more competitive.

Big Data Abounds, Except in Verifying Voters

In all of these instances, obstructing the timely processing of voter registrations and other piled-on bureaucracy—namely adding ID requirements that have nothing to do with the legal basis to be an eligible voter—appear to be the GOP’s latest anti-voter tools.

Perhaps no one should be surprised that the GOP has found more moves to try to thwart its opponent’s base in battleground contests. But it is more than ironic that in an era dominated by big data, the latest Republican voter suppression tactic is obstructing the timely processing of basic voter-verifying information.

Also Available on: www.commondreams.org