Will 2020’s Purple State Voters Reverse Extreme Republican Gerrymanders?

(Image / https://rslc.gop/)

The presidential and U.S. Senate races have dominated the 2020 election season. But down the ballot, races for state legislature and governor will determine the political complexion in many purple states for the next decade—much longer than the next president will serve.

The reason these races have such a long-lasting impact is that the winners of state legislative elections this fall will redraw the boundaries for their legislative districts and for U.S. House seats. A decade ago, the Republican Party, who saw their presidential candidate lose in 2008 by nearly 10 million votes, targeted 107 races in 16 states with the goal of redrawing maps affecting 190 U.S. House seats. The common term for aggressively segregating voters into districts is gerrymandering.

The GOP effort, called RedMap, was unchecked at that time by Democrats, even as it focused on states won by President Obama. RedMap succeeded and led to GOP supermajorities in state capitols and U.S. House delegations. These majorities have been behind the most extreme GOP actions of the past decade at the state level and in Congress; whether resisting or rolling back safety nets, civil rights, reproductive choice, gun controls, environmental regulation and labor laws.

In 2016, longtime political reporter David Daley published a book explaining how Republicans instituted some of the most extreme gerrymanders in American history, where the GOP drew districts to facilitate winning majorities and sought to “crack or pack” blue epicenters. Since the publication of Rat F**ked: The True Story Behind The Secret Plan to Steal America’s Democracy, the Democratic Party has vowed to not repeat this history.

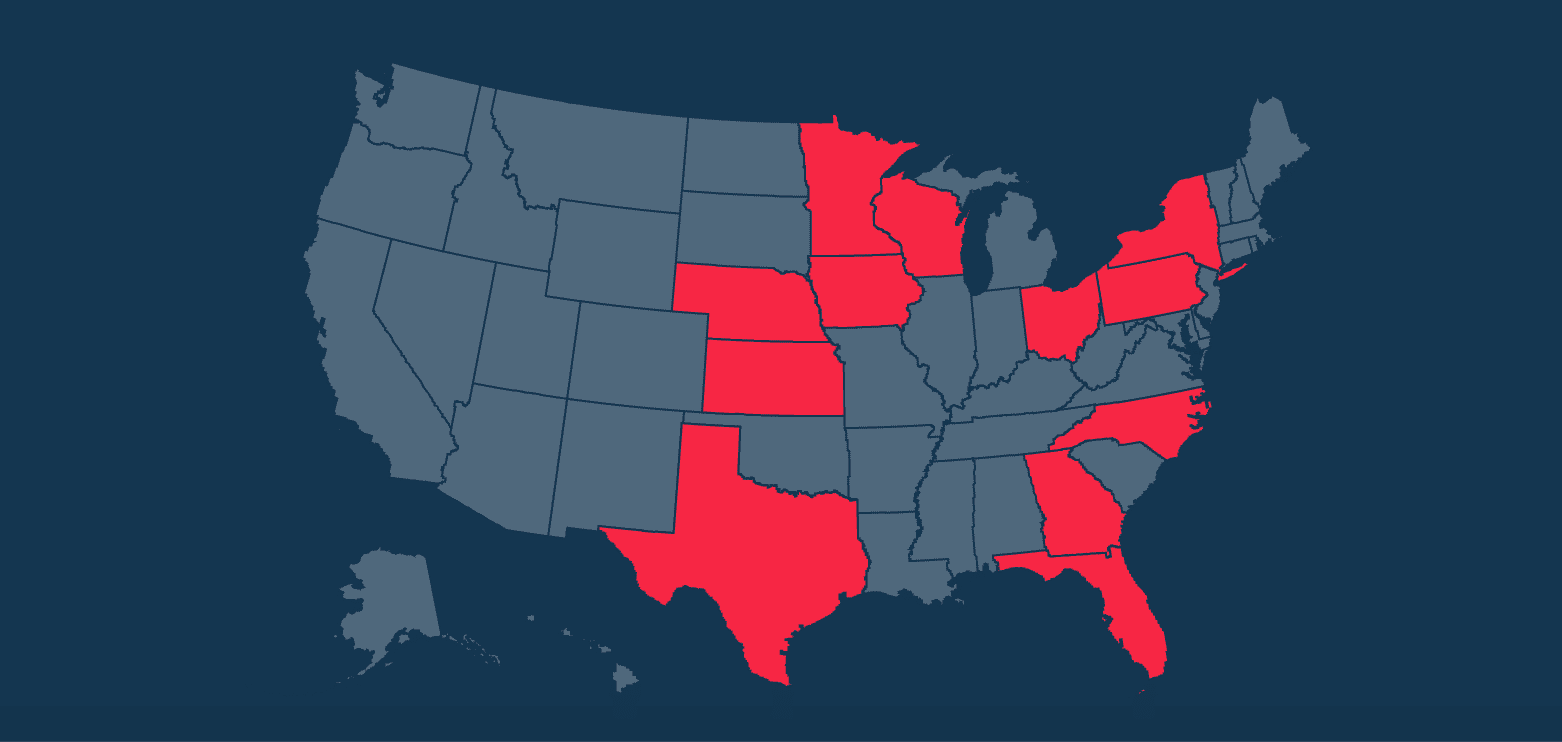

Voting Booth’s Steven Rosenfeld interviewed David Daley about the races that will determine this decade’s political complexion in purple states such as Wisconsin, Michigan, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, Arizona, Texas, Kansas, North Carolina, Georgia and Florida.

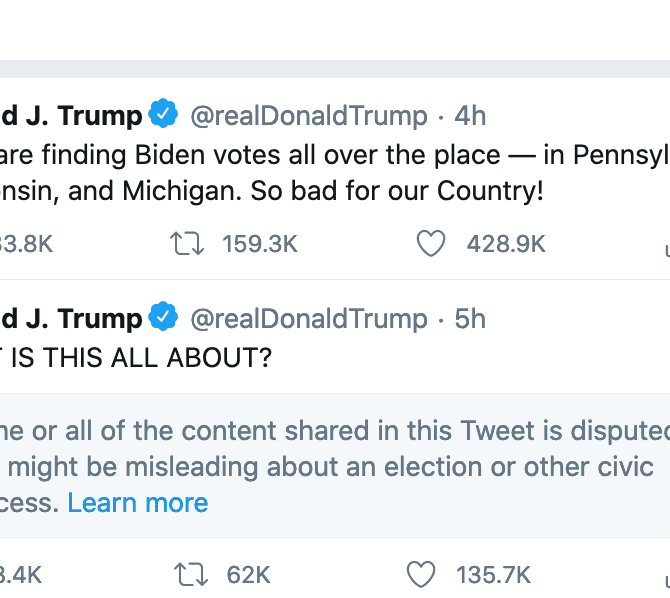

Key down-ballot contests are as hard-fought as the races at the top of the ticket, Daley said. Even if President Trump and Senate Republicans are resoundingly defeated, there may still be ferocious post-Election Day challenges and legal fights if mapmaking power is in play.

Steven Rosenfeld: The volume of votes already cast in the 2020 election is remarkable. More than 52 million as of October 23. Most people are focused on the White House and Congress. Your focus is state legislative chambers and who will draw or veto the political maps that will last for a decade starting in 2021. What impact will record voter turnout have?

David Daley: I don’t think anybody knows what impact the turnout will have. I think it’s dangerous to assume partisan enthusiasm one way or another from an early turnout number. It seems that both sides’ turnout is fairly well matched at this point. Democrats have been aggressively seeking mail-in ballot voting in a lot of states, and they seem to have an edge there. But as far as early in-person voting goes, I think it’s hard to say.

There’s a lot of ways of looking at it. In some states there is a sense that some of the really contested statehouse races that are so important for 2021’s redistricting are perhaps trickling up, and that they are perhaps funneling more voters in, and more enthusiasm. In the past, the old political science model used to suggest that people trickled down [the ballot, first voting for president]. There are a lot of states where all these local races have been so important that they could help Democrats up and down the ballot.

SR: Can you give me some examples?

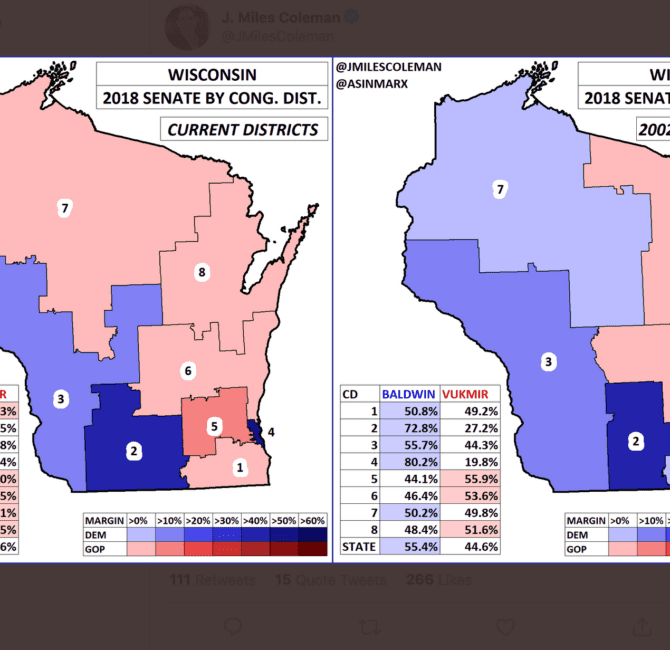

DD: I think North Carolina. I think Texas, certainly. Wisconsin is one of those states where Democrats have been really fired up in [state] assembly and senate races simply to try to hold onto Gov. [Tony] Evers’ veto power. Democrats have really organized to try to hold onto state legislative power there—to simply have veto power over bad maps that could entrench Republican control for another decade.

SR: When I look at the National Conference of State Legislatures’ chart on the partisan composition of each chamber and who holds the governor’s seat, and look at the targeted states put out by Democrats and Republicans, there aren’t that many states in play. I think the closest ones—with the fewest seats needed to flip a chamber—would be Arizona and New Hampshire. That’s two or three seats. Then the number goes up to four or more seats with Florida, Michigan, North Carolina, Pennsylvania.

DD: It’s tricky. Let me walk you through the way I see it…

Arizona is certainly flippable by Democrats this year. That would have a big impact with regard to policy [reforms and new laws] in that state. But it has an independent redistricting commission. A flip there is not going to have any change on its [political] maps over the course of the next decade.

Michigan as well. It passed an independent redistricting commission in 2018. A flip there would be useful in regards to policy. You already have a Democratic governor in place who could veto the most egregious maps. But there’s a commission that will be in charge.

North Carolina, the governor does not have veto power there. So Democrats either take the House or the Senate [this November], or they have no say over the [redistricting] process over the next decade. And there has been an all-out attempt to win one or both chambers. I think it’s 50-50 probably that they could get one. It depends how things break. It’s a brand-new map in North Carolina, after the state Supreme Court tossed the old ones. No one has ever run on this map before. It’s believed to have a slight Republican lean, but much less of a Republican lean than the one that they were running on in previous years.

Florida, on the other hand. That map has withstood all legal challenges over the course of this decade. I think Florida is probably a very difficult flip. I don’t see that one being in the cards.

Georgia is a very difficult flip. I don’t see that being in the cards.

Texas, Democrats need nine seats [to flip the House]. They are very aggressively going after them. There are the 18 target districts that went for Beto [O’Rourke in his U.S. Senate race against Sen. Ted Cruz] but have a Republican statehouse member. Democrats have a robust target list in Texas, but still need everything to go right. But they are closer to a flip than they have been at any point in time.

In other states, Democrats are playing defense. Like Wisconsin, [where] they are trying to uphold the veto by a Democratic governor. If Republicans are able to gain a supermajority, then they [the GOP] could override that veto, and they would have pretty much complete control over mapmaking.

Pennsylvania will not be as bad as it was in 2021 because there’s a Democratic governor who can get in the way [of a Republican-majority legislature] and make certain that the Democratic interests are considered. Both of the chambers there are still very tough lifts for Democrats to alter.

Democrats are on the offense in Minnesota, looking for a trifecta [control of both legislative chambers and the governor’s seat].

And Democrats in Kansas are trying to hold onto the governor’s veto because you have a Democratic governor who could conceivably veto the Republican map as long as Republicans don’t win a supermajority there.

SR: This landscape strikes me as not being as one-sided as what you wrote about in your book, which focused on 2010’s races and the Republicans’ extreme gerrymanders that followed in 2011.

DD: I think you are right. The political maps from 2011 have proven astonishingly enduring. These are some of the most effective gerrymanders of all time. Usually, the gerrymander melts away after two or three election cycles because the politics change, people die, the [state’s] demographics evolve, but these have lasted for a decade. But Democrats have very effectively found ways to win seats at the table, where possible. They have won veto power by winning governorships in Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania. They have clawed back in Texas where there are in position with a good year [outcome in 2020] to have a seat at the table.

They [Democrats] have pursued litigation, where possible, and they have won fairer maps in Virginia that resulted in a flip in 2019. They got a fairer map in North Carolina, so they’ve got a chance at a better map [for the next decade] there. The same with Pennsylvania. The demographics, meanwhile, have changed in Arizona, putting a chamber perhaps in play there. I think Democrats have done a pretty good job of thinking strategically about the levers that were available to them in each state and trying to maximize it. In some states, it’s the governor. In some states, it’s litigation. In some states, it’s trying to win back a chamber. They have systematically thought it through. It’s an uphill run, though, because you’re running against those maps, so as you’re doing it, you have a hand tied behind your back.

SR: One of the most striking aspects of your book was how aggressive the Republicans were with running political ads and attacks at the local level—to win these legislative majorities. Local men and women were viciously smeared. Are 2020’s targeted races as nasty?

DD: Oh yeah. Both sides are fully aware of the stakes in these races. You are seeing hundreds of thousands of dollars, millions of dollars in some cases, being funneled into state house and state senate races that once upon a time might have been sleepy. If you are in a competitive state house or state senate race in one of those key states, it is probably a seven-figure race on both sides because that’s what’s at stake for the next decade. There’s mapmaking power, and both parties realize it. It will be deeply hard-fought.

Take North Carolina. Everybody knows in all of these states it’s only a handful of swing districts. In some ways, it’s like a presidential campaign. Everybody knows there’s only a handful of states that matter. You invest all of your resources aggressively there. In North Carolina and a lot of states like this, a lot of the down-ballot races are sleepy, and then there are some that are these seven-figure slugfests.

SR: Looking past Election Day, the other big factor on this decade’s forthcoming political maps will be not just the 2020 winners redrawing district lines, but the census count—the people and voters who will be sliced and diced to create political districts. What do you think the impact will be of a truncated census count?

DD: I don’t think anybody knows fully. We don’t know what the undercount is going to be or where it will be. There’s a huge impact of federal funding dollars, and which communities get the resources they will need and which communities don’t [get resources]. The next impact is on reapportionment, the number of U.S. House representatives that each state receives. There are a lot of questions on whether an undercount will shift political power in some ways. This power has been moving. Midwestern and New England states are losing seats. Southern and southwestern states are gaining seats. It’s really hard to predict which states will gain or lose members [of Congress] based on reapportionment and the census. That, in turn, affects the Electoral College [where votes are allocated based on the congressional delegation size].

If there’s an undercount of Latino voters in Texas, could Texas lose seats instead of gaining seats? If there’s an undercount in Florida of minority groups, could that offset an undercount in California? It’s hard to say until you see exactly where the numbers are. But then you have the additional question of citizenship data. The Trump administration has made it really clear that they want the citizenship data to be provided to state legislatures for redistricting purposes. There’s been a longtime standard that state legislatures have followed the national standard of drawing lines based on total population, not the citizen voting age population. If you begin to see states using citizenship data to redistrict, based on citizen voting age population, you are going to see state legislatures where the political power shifts to older, rural, whiter and more conservative areas.

SR: I always thought that strategy was the last play or the last stand in the Republican Party’s decline—the destiny by demography scenario where, as white America shrinks and non-white America’s population grows, the last big structural play they have is only counting the citizen voting age population when making political districts versus the total population of an area.

DD: I think that’s right.

SR: So here we are, two weeks out. And it would be premature to draw any conclusion because these national and state voter turnout figures are too generalized, compared to the local races. But the stakes are enormous—the partisan complexions of the country’s purple states.

DD: I think what’s clear is the next decade is on the line in all of these states. What you just said is exactly right. Democrats have had this blind faith in the idea that demography is destiny for some time. What Republicans have shown is you can govern from the minority quite effectively and quite reliably through gerrymandering, and rule rigging, and voter suppression.

[South Carolina Sen.] Lindsey Graham once said they weren’t making old white men fast enough for the Republican Party to not have to evolve at some point. Yet, through all of these other techniques, they’ve managed to avoid evolving. And indeed, if they have evolved, it’s been further toward the right and further toward that base by drawing themselves districts and entrenching their power in places that look less and less like the rest of the country. It seems like it can’t be a long-term strategy, but it sure keeps lasting, and [it] sure looks difficult to find a way to defeat it.

But if that defeat is to come, down-ballot races in 2020 are going to play an outsized role.

SR: We’re only talking about 10 or 12 states that might be in play.

DD: That’s all we talk about in a presidential election too. There are very few states that don’t have both houses of its state legislature in the hands of the same party—as far as houses and senates. Nebraska is an oddball in that [it has one chamber], but every place else is all blue or all red, except for Minnesota. So that eliminates the number of possible pickups, right?

In 2010, when the Republicans were looking to run RedMap, very few seats separated Democrats from Republicans in [state legislatures in] all of these states. That’s why they were able to do it. Democrats held Pennsylvania, but their lead in the Pennsylvania statehouse was 102 to 101. It was super-close in Michigan. Democrats had Ohio. They had North Carolina, and Republicans took them all in 2010’s election. And then redistricted them in such a way that Democrats haven’t come back all decade in most of these states.

Wisconsin is not a state that the Democrats are trying to flip; they are just trying to hold onto veto power with these maps a decade later. In contrast, in Texas and Arizona, a demographic change has come around and put those states in play. Litigation in other states has put [those] states in play. And then polarization elsewhere has ensured that other states will not be in play.

SR: Do you think there will be post-Election Day litigation over these down-ballot races if they are close, even if the results of the presidential election are not in dispute?

DD: It depends on how close they are… Both sides know the stakes. If control of Texas’s statehouse is tied or within one seat… There will be close races. Remember Virginia back in 2017, when the last race [deciding the House majority] was tied? They pulled a piece of paper out of a film canister or something to settle it. [Republicans won.] Crazy things happen…